Overview

Tricuspid valve regurgitation

Tricuspid valve regurgitation

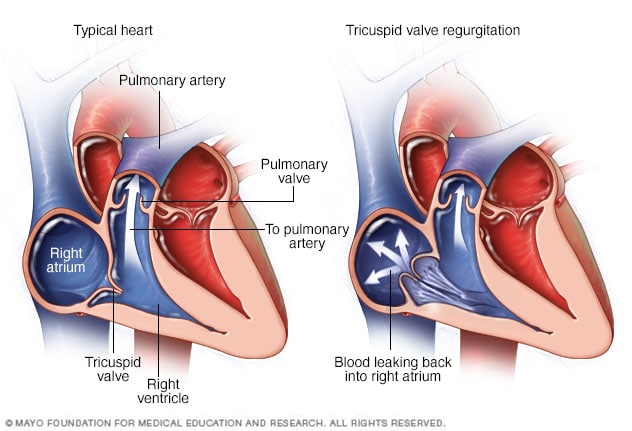

In tricuspid valve regurgitation, the valve between the two right heart chambers doesn't close properly. The upper right chamber is called the right atrium. The lower right chamber is called the right ventricle. As a result, blood flows backward.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation is a type of heart valve disease. The valve between the two right heart chambers doesn't close as it should. Blood flows backward through the valve into the upper right chamber. If you have tricuspid valve regurgitation, less blood flows to the lungs. The heart has to work harder to pump blood.

The condition also may be called:

- Tricuspid regurgitation.

- Tricuspid insufficiency.

Some people are born with heart valve disease that leads to tricuspid regurgitation. This is called congenital heart valve disease. But tricuspid valve regurgitation also may occur later in life due to infections and other health conditions.

Mild tricuspid valve regurgitation may not cause symptoms or require treatment. If the condition is severe and causing symptoms, medicine or surgery may be needed.

The tricuspid valve's job is to allow blood flowing into the heart from the body to flow to the right ventricle where it's pumped to the lungs for oxygen. If the tricuspid valve is leaky, blood can flow backwards, causing the heart to pump harder. Over time, the heart becomes enlarged and functions poorly.

Valve conditions in children and Ebstein anomaly

Products & Services

Symptoms

Tricuspid valve regurgitation often doesn't cause symptoms until the condition is severe. It may be found when medical tests are done for another reason.

Symptoms of tricuspid valve regurgitation may include:

- Extreme tiredness.

- Shortness of breath with activity.

- Feelings of a rapid or pounding heartbeat.

- Pounding or pulsing feeling in the neck.

- Swelling in the belly, legs or neck veins.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment for a health checkup if you get tired very easily or feel short of breath with activity. You may need to see a doctor trained in heart conditions, called a cardiologist.

Causes

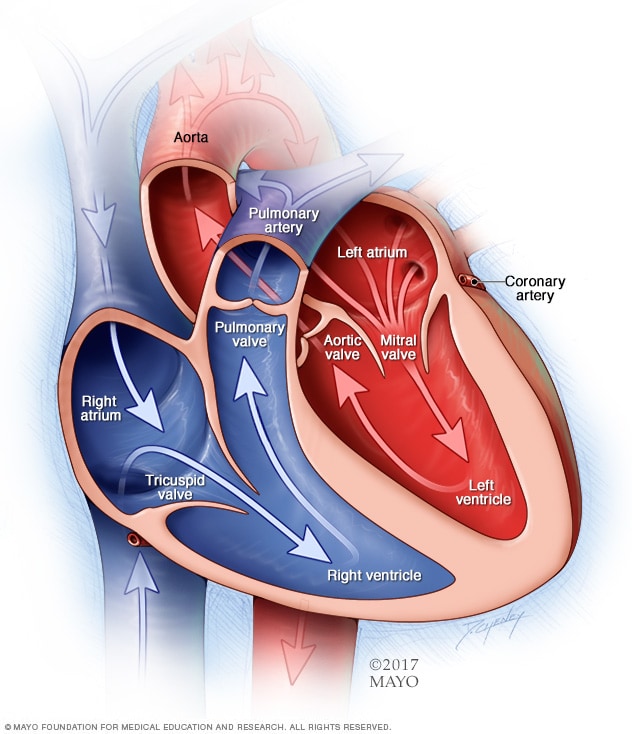

Chambers and valves of the heart

Chambers and valves of the heart

A typical heart has two upper and two lower chambers. The upper chambers, the right and left atria, receive incoming blood. The lower chambers, the more muscular right and left ventricles, pump blood out of the heart. The heart valves help keep blood flowing in the right direction.

To understand the causes of tricuspid valve regurgitation, it may help to know how the heart and heart valves typically work.

A typical heart has four chambers.

- The two upper chambers, called the atria, receive blood.

- The two lower chambers, called the ventricles, pump blood.

Four valves open and close to keep blood flowing in the correct direction. These heart valves are:

- Aortic valve.

- Mitral valve.

- Tricuspid valve.

- Pulmonary valve.

The tricuspid valve is between the heart's two right chambers. It has three thin flaps of tissue, called cusps or leaflets. These flaps open to let blood move from the upper right chamber to the lower right chamber. The valve flaps then close tightly so blood doesn't flow backward.

In tricuspid valve regurgitation, the tricuspid valve doesn't close tightly. So, blood leaks backward into the upper right heart chamber.

Causes of tricuspid valve regurgitation include:

- A heart problem you're born with, also called a congenital heart defect. Some congenital heart defects affect the shape of the tricuspid valve and how it works. Tricuspid valve regurgitation in children is usually caused by a rare heart problem present at birth called Ebstein anomaly. In this condition, the tricuspid valve does not form correctly. It also is lower than usual in the lower right heart chamber.

- Marfan syndrome. This condition is caused by changes in genes. It affects the fibers that support and anchor the organs and other structures in the body. It's occasionally associated with tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Rheumatic fever. This complication of strep throat can cause permanent damage to the heart and heart valves. When that happens, it's called rheumatic heart valve disease.

- Infection of the lining of the heart and heart valves, also called infective endocarditis. This condition can damage the tricuspid valve. IV drug misuse increases the risk of infective endocarditis.

- Carcinoid syndrome. This condition occurs when a rare cancerous tumor releases certain chemicals into the bloodstream. It can lead to carcinoid heart disease, which damages heart valves, most commonly the tricuspid and pulmonary valves.

- Chest injury. An injury to the chest, such as from a car accident, may cause damage that leads to tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Pacemaker or other heart device wires. Tricuspid valve regurgitation might happen if wires from a pacemaker or defibrillator cross the tricuspid valve.

- Heart biopsy, also called an endomyocardial biopsy. Heart valve damage can sometimes happen when a small amount of heart muscle tissue is removed for examination.

- Radiation therapy. Rarely, radiation therapy for cancer that is focused on the chest area can cause tricuspid valve regurgitation.

Risk factors

A risk factor is something that makes you more likely to get a sickness or other health condition.

Things that can increase the risk of tricuspid valve regurgitation are:

- An irregular heartbeat called atrial fibrillation (AFib).

- Being born with a heart problem, called a congenital heart defect.

- Damage to the heart muscle, including heart attack.

- Heart failure.

- High blood pressure in the lungs, also called pulmonary hypertension.

- Infections of the heart and heart valves.

- History of radiation therapy to the chest area.

- Use of some weight-loss drugs and medicines to treat migraines and mental health disorders.

Complications

Tricuspid valve regurgitation complications may depend on how severe the condition is. Possible complications of tricuspid regurgitation include:

- An irregular and often rapid heartbeat, called atrial fibrillation (AFib). Some people with severe tricuspid valve regurgitation also have this common heart rhythm disorder. AFib has been linked to an increased risk of blood clots and stroke.

- Heart failure. In severe tricuspid valve regurgitation, the heart has to work harder to pump enough blood to the body. The extra effort causes the lower right heart chamber to get bigger. Untreated, the heart muscle becomes weak. This can cause heart failure.