Overview

Cerebral cavernous malformation

Cerebral cavernous malformation

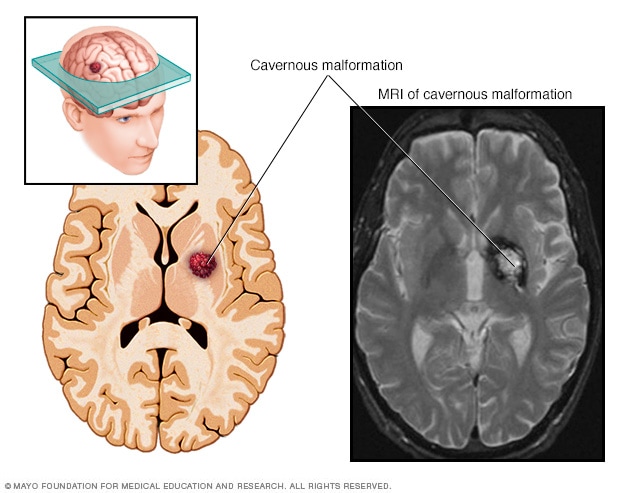

A cerebral cavernous malformation is an irregularly formed blood vessel, shaped like a small mulberry. It can form in the brain or spinal cord and may result in a wide range of neurological symptoms.

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) are groups of tightly packed, irregular small blood vessels with thin walls. They may be present in the brain or spinal cord. The vessels contain slow-moving blood that's usually clotted. CCMs look like small mulberries. In some people, CCMs can cause blood to leak in the brain or spinal cord.

CCMs vary in size. Often they are less than half an inch (1 centimeter). Most CCMs are sporadic. This means the CCM occurs as a single cavernous malformation and there isn't a family history. But about 20% of CCMs affect people of the same family. These are known as familial CCMs. Familial CCMs are related to a gene change passed down through families. People with familial CCMs usually have multiple cavernous malformations.

A CCM is one of several types of brain vascular malformations that contain irregular blood vessels. Other types of vascular malformations include:

- Arteriovenous malformation (AVM).

- Dural arteriovenous fistula.

- Developmental venous anomaly (DVA).

- Capillary telangiectasia.

For people who have the sporadic form, it's common to have both a DVA and a CCM.

CCMs may leak blood and lead to bleeding in the brain or spinal cord, known as a hemorrhage. Brain hemorrhages can cause many symptoms, such as seizures.

Depending on the location, CCMs also can cause stroke-like symptoms such as trouble with movement or feeling in the legs and sometimes the arms. CCMs also may cause bowel and bladder symptoms.

Products & Services

Symptoms

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) may not cause symptoms. Sometimes when the CCM occurs on the outer surface of the brain, it can cause seizures.

And CCMs found in other areas can have a variety of symptoms. These include CCMs in the spinal cord, the brainstem linking the spinal cord and brain, and the basal ganglia in the inner brain. For example, bleeding in the spinal cord may cause bowel and bladder symptoms or trouble with movement or feeling in the legs or arms.

Generally, symptoms of CCMs may include:

- Seizures.

- Bad headaches.

- Weakness in the arms or legs.

- Numbness.

- Trouble speaking.

- Poor memory and attention.

- Trouble balancing and walking.

- Vision changes, such as double vision.

Symptoms can get worse over time with repeated bleeding. Bleeding can happen again soon after the first bleed or much later. In some people, a repeat bleed may never occur.

When to see a doctor

Seek medical help right away if you experience any symptoms of a seizure. Also get immediate medical help if you have symptoms that suggest a cerebral cavernous malformation or brain bleeding.

Causes

Most cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) are known as the "sporadic form." They occur as a single malformation without any family history. The sporadic form often has an associated developmental venous anomaly (DVA), which is an irregular vein with a witch's broom appearance.

However, about 20% of people with a CCM have a genetic form. This form is passed down in families, known as familial cavernous malformation syndrome. People with this form may have family members with CCMs, most often with more than one malformation. A diagnosis can be confirmed by a genetic test that requires a blood or saliva sample. Genetic testing is often recommended for people who have:

- MRI evidence of multiple CCMs without a DVA.

- A family history of CCMs.

Radiation to the brain or spinal cord also may result in CCMs within 2 to 20 years afterward. Other rare syndromes may be associated with CCM.

Risk factors

Most cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) have no clear cause. But the form that's passed down through families can cause multiple CCMs, both to start with and over time.

To date, research has identified three genetic changes responsible for cavernous malformations passed down through families. Almost all familial cases of cavernous malformations have been traced through those genetic changes.

Familial CCMs are passed down in families through a change in one of these genes:

- KRIT1, also called CCM1.

- CCM2.

- PDCD10, also called CCM3.

These genes are responsible for affecting the leakiness of blood vessels and the proteins that keep the blood vessel cells together.

Complications

The most serious complications of cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) stem from repeated bleeding, known as hemorrhages. CCMs that bleed over and over again may cause a hemorrhagic stroke and lead to damage in the nervous system.

Bleeding is more likely to return in people with prior hemorrhages. Bleeding also is more likely to happen again with CCMs located in the brainstem.