Overview

Craniotomy

Craniotomy

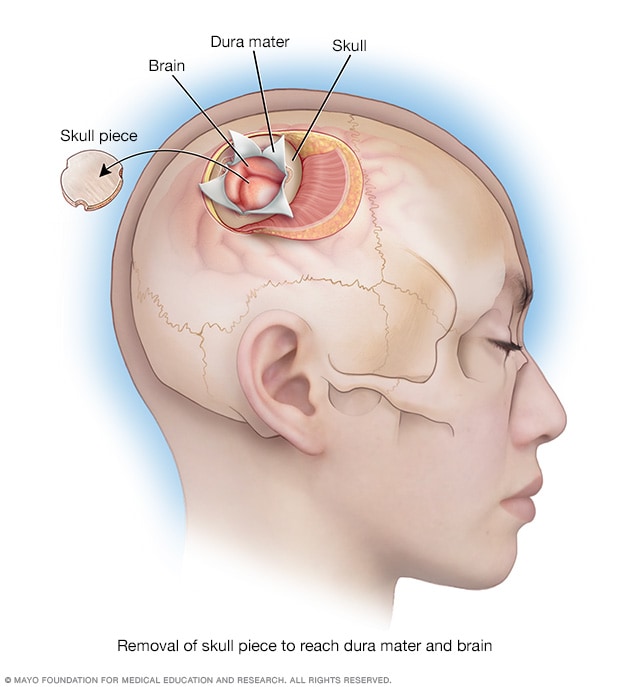

During a craniotomy, a piece of skull is removed to expose the tough covering over the brain, known as the dura mater, and the brain.

A craniotomy is a surgical procedure to remove part of the skull to reach the brain.

The surgery is used to treat brain tumors, bleeding in the brain, blood clots or seizures. It also may be done to treat a bulging blood vessel in the brain, known as a brain aneurysm. Or a craniotomy can treat blood vessels that did not form properly, known as a vascular malformation. If an injury or stroke has caused brain swelling, a craniotomy can relieve the pressure on the brain.

Craniotomy types

There are several types of craniotomies. The type of craniotomy that is used depends on which area of the skull is removed for treatment. Craniotomy types include:

- Bifrontal craniotomy. A surgeon removes part of the front of the skull behind the hairline. This may be done to treat a brain aneurysm.

- Supraorbital craniotomy. This surgery involves removing an area of the skull just above the eye socket. The opening is usually made through a short incision hidden in the eyebrow, which is why it is sometimes called an eyebrow craniotomy. This approach allows surgeons to reach the front of the brain and skull base to treat conditions such as brain tumors or aneurysms, while keeping the scar less visible and limiting the size of the bone opening.

-

Pterional craniotomy. A surgeon removes part of the skull on the side of the head in front of and above the ear. Another name for this type of surgery is frontotemporal craniotomy.

Pterional craniotomy can be done to treat brain aneurysms, brain tumors, blood clots, epilepsy and arteriovenous malformations. Sometimes a pterional keyhole craniotomy is done, which removes a smaller area of the skull.

- Suboccipital craniotomy. A surgeon removes a piece of the base of the skull in the lower area at the back of the head. This type of craniotomy is done to treat a condition where brain tissue extends into the spinal canal, known as a Chiari malformation. It also can treat brain tumors, aneurysms, cavernous malformations and arteriovenous malformations.

- Retrosigmoid keyhole craniotomy. A small hole is cut in the skull behind the ear. This type of surgery may be used to treat an aneurysm. It also may be used to treat a noncancerous tumor on the nerve leading from the inner ear to the brain. This type of tumor is known as an acoustic neuroma or a vestibular schwannoma. A retrosigmoid keyhole craniotomy is a type of suboccipital craniotomy. It's a less invasive version that uses a smaller opening behind the ear to reach the tumor, which may reduce recovery time and side effects.

- Middle fossa craniotomy. The surgeon makes an opening in the skull just above the ear. This allows the surgeon to reach the middle part of the brain's base, called the middle cranial fossa. Surgeons often use this approach to remove smaller tumors or to treat problems in the inner ear canal and nearby bone.

- Far lateral approach. For this surgery, part of the skull behind the ear is removed. The surgeon uses a thin, flexible tube known as an endoscope to remove a tumor.

- Orbitozygomatic approach. The surgeon removes small parts of the eye socket and cheekbone for better access. It's used for complex tumors or blood vessel problems. This approach helps the surgeon reach deep or hard-to-access areas at the base of the skull. The approach reduces the need to move or press on brain tissue.

Variations on craniotomy surgery

Other procedures are similar to craniotomy, but they have a few differences in why and how they're done.

Craniectomy

A craniectomy is similar to a craniotomy, but the removed skull bone is not replaced at the end of the surgery. This is usually done in emergencies when the brain is swelling dangerously.

Why it's done

- After traumatic brain injury.

- After major stroke that blocks blood flow through the middle cerebral artery, one of the brain's major blood vessels.

- When very high pressure inside the skull doesn't get better with medicine or with a ventilator to help the person breathe.

Key points

- The piece of skull bone is either stored or discarded.

- It gives the brain room to swell safely without being squeezed.

- A second surgery called a cranioplasty may be needed later to repair the skull.

Cranioplasty

Cranioplasty is surgery to repair the shape of the skull, usually following a previous craniectomy. This repair typically uses the original piece of skull removed during the craniotomy. It may use artificial materials if the original piece of skull can't be used.

Why it's done

- To protect the brain by covering the opening in the skull.

- To restore the shape of the head.

- Sometimes, to help the brain work better, especially if symptoms appeared after the skull piece was removed.

Key points

- This surgery is done to repair the skull, not to treat the original brain condition.

- It's usually a planned procedure that happens after the brain swelling has gone down.

Burr hole procedure

A burr hole is a small hole drilled into the skull without removing a bone flap to treat or diagnose brain conditions.

Why it's done

- To drain old blood that has built up on the surface of the brain.

- To insert a tube that helps remove extra fluid from the brain, known as a ventricular drain.

- To take a small sample of brain tissue for testing, called a biopsy.

- To reach fluid-filled spaces in the brain when placing a device that helps drain excess fluid, known as a shunt.

Key points

- It is a minimally invasive procedure, meaning it uses a small opening and causes less disruption to the skull and brain.

- No large piece of bone is removed — only a small hole is made.

- Sometimes, it can be done with local anesthesia, so the person stays awake but the area is numbed.

Why it's done

A craniotomy may be done to get a sample of brain tissue for testing. Or a craniotomy may be done to treat a condition that affects the brain.

Craniotomies are the most common surgeries used to remove brain tumors. A brain tumor can put pressure on the skull or cause seizures or other symptoms. Removing a piece of the skull during a craniotomy gives the surgeon access to the brain to remove the tumor. Sometimes a craniotomy is needed when cancer that begins in another part of the body spreads to the brain.

A craniotomy also may be done if there is bleeding in the brain, known as a hemorrhage, or if blood clots in the brain need to be removed. A bulging blood vessel, known as a brain aneurysm, can be repaired during a craniotomy.

A craniotomy also can be done to treat an irregular blood vessel formation, known as a vascular malformation. If an injury or stroke has caused brain swelling, a craniotomy can relieve the pressure on the brain.

Risks

Craniotomy risks vary depending on the type of surgery. In general, risks may include:

- Changes in the shape of the skull.

- Numbness.

- Changes in smell or vision.

- Pain while chewing.

- Bleeding or blood clots.

- Changes in blood pressure.

- Seizures.

- Weakness and trouble with balance or coordination.

- Trouble with thinking skills, including memory loss.

- Stroke.

- Excess fluid in the brain or swelling.

Infections after craniotomy are possible, though not very common. A leak of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord can occur. This is known as a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. How commonly a CSF leak occurs after craniotomy depends on several factors, including the type of craniotomy performed.

How you prepare

Your healthcare team lets you know what you need to do before a craniotomy. To prepare for a craniotomy, you may need several tests such as:

- Neuropsychological testing. This can test your thinking, known as cognitive function. The results serve as a baseline to compare with later tests and can help with planning for rehabilitation after surgery.

-

Brain imaging such as MRI or CT scans. Imaging helps your healthcare team plan the surgery. For example, if your surgery is to remove a brain tumor, brain scans help the neurosurgeon see the location and size of the tumor. You may have a contrast material injected through an IV into a vein in your arm. The contrast material helps the tumor show up more clearly in the scans.

A type of MRI called a functional MRI (fMRI) can help your surgeon map the areas of the brain. An fMRI shows small changes in blood flow when you use certain areas of your brain. This can help the surgeon avoid areas of the brain that control important functions such as language.

Food and medicines

Your healthcare team tells you whether you need to stop taking certain medicines before surgery. You also may be prescribed a medicine to take before surgery. The care team also may tell you what you can eat or drink before a craniotomy.

-

Medicine changes. Before surgery, tell your healthcare team about any medicines you take or any allergies you have to medicines. Include medicines that need a prescription and medicines you buy without a prescription. Include vitamins, herbal products and other supplements.

If you take the diabetes medicine metformin and you get IV contrast during an imaging exam, you may have side effects. To help avoid this, your healthcare professional may tell you not to take some medicines, including metformin, for 48 hours after you get the contrast.

Blood-thinning medicines affect clotting and bleeding. Before your procedure, both the healthcare professional doing your procedure and the healthcare professional who manages these medicines need to decide if your medicines need to change. After your procedure is scheduled, talk with your healthcare team about your medicines as soon as you can. If you are not sure whether you take blood-thinning medicine, contact your healthcare team or pharmacist.

Some people need to take an antibiotic or another medicine before surgery. Ask your healthcare team whether you need to take any medicines before the procedure.

- What you can eat and drink before surgery. Do what your healthcare team tells you about when to stop eating and drinking before surgery.

What you can expect

Your head may be shaved before a craniotomy. Typically, you lie on your back for surgery. But you may be on your stomach or side or in a sitting position. Your head may be placed in a frame. Children under age 3 don't have a head frame during a craniotomy.

If you have a brain tumor called glioblastoma, you may be given fluorescent contrast material. The material makes the tumor glow under fluorescent light. This light helps the surgeon separate the tumor from other brain tissue.

You may be put into a sleeplike state for the surgery. This is known as general anesthesia. Or you may be awake for part of the surgery if your surgeon needs to check brain functions such as movement and speech during the operation. This is to ensure that the surgery doesn't affect important brain functions. If the area of the brain being operated on is near the language areas of the brain, for example, you're asked to name objects during the surgery.

With awake surgery, you may be in a sleeplike state for part of the surgery and then awake for part of the surgery. Before surgery, a numbing medicine is applied to the area of the brain to be operated on. You're also given medicine to help you feel relaxed.

During the procedure

During a craniotomy, a neurosurgeon makes a cut in the scalp and folds the skin back. Then the surgeon uses a surgical drill to carefully cut a piece of the skull. That piece is temporarily removed to show the part of the brain that needs treatment. Next, the tough outer covering of the brain, known as the dura mater, is opened. In some cases, the surgeon also needs to make a cut into the brain itself. The area of the skull where the cut is made depends on the type of craniotomy being performed.

What happens during brain surgery

Once the brain is exposed, the surgeon begins treatment based on your condition:

- If a sample of tissue is needed for testing, known as a biopsy, the sample is taken.

- If a tumor is being treated, the surgeon works to remove it.

- If a blood vessel is being treated, the surgeon works to reshape it.

- If there is an aneurysm, the surgeon may place clips to stop blood flow to it.

- If there is bleeding or a blood clot, the surgical team removes it during the procedure.

Techniques that may be used during surgery might include:

- Computer assistance and imaging during surgery. Surgeons often use computers and special brain scans, such as MRI, during the operation. This is called intraoperative imaging. It helps the surgeon see the location and size of a tumor or confirm that an aneurysm has been successfully treated.

- Awake brain surgery. In some procedures, you may be kept awake and asked questions during surgery. This helps the surgeon avoid parts of the brain that control speech or other important functions. For example, you might be asked to name objects shown on slides.

- Intraoperative cortical stimulation. The surgeon may apply a small amount of electricity to parts of the brain during surgery. This shows which areas control speech, movement or other vital functions. It helps the surgeon remove only the problem area and protect healthy brain tissue. This process may be done along with special imaging, such as functional MRI (fMRI), or other mapping tests during the procedure.

If you are having surgery for a brain tumor

The goal of surgery is usually to remove the entire tumor. However, if the tumor is very close to important areas of the brain that control speech, movement or breathing, your surgeon may leave part of it in place to avoid causing damage. In that case, additional treatments such as radiation or chemotherapy may be needed later.

Sometimes, the surgeon places treatments directly in the brain during the craniotomy. These treatments may include chemotherapy wafers or targeted radiation.

Closing the skull and scalp

When surgery on the brain is finished, the dura mater is closed and sealed. The piece of skull that was removed is put back into place. It is secured with tiny metal plates and screws. These hardware pieces usually are made of titanium so you can still have MRI scans in the future. Finally, the skin is closed using stitches or staples.

After the procedure

After a craniotomy, a small tube may come out of your skull. This is a drain that allows extra fluid to flow out of your skull. You also may have other tubes to allow blood to drain. The drains usually are removed after a few days.

About 1 to 3 days after surgery, you may need an imaging test such as an MRI scan or a CT scan. This test can show your surgeon if a tumor was removed completely.

You may need to recover in the hospital for about 2 to 4 days after a craniotomy. The length of your hospital stay may vary depending on the reason for your surgery, your health and whether you need other treatments.

It can take several months to fully heal after a craniotomy.

If you take blood-thinning medicines and these medicines were stopped before your procedure, talk with your healthcare team about when to restart these medicines. Because some common pain relievers affect blood thinning, talk with your healthcare team about what you can take for pain after surgery.

Results

After a craniotomy, you'll need follow-up appointments with your healthcare team. Tell your healthcare team right away if you're having any symptoms after surgery.

You may need blood tests or imaging tests such as MRI scans or CT scans. These tests can show if a tumor has come back or if an aneurysm or other condition remains. Tests also determine if there are any long-term changes in the brain.

During surgery, a sample of the tumor may have gone to a lab for testing. Testing can determine the type of tumor and what follow-up treatment may be needed.

Some people need radiation or chemotherapy after a craniotomy to treat a brain tumor. Some people need a second surgery to remove the rest of the tumor.

Long-term side effects of craniotomy

Sometimes, surgical scars can remain painful or sensitive for years after a craniotomy. This is often due to nerve endings trapped in scar tissue or chronic inflammation around titanium hardware. The pain may feel sharp, burning, tight or itchy.

These treatments for long-term scar pain after craniotomy may provide relief:

- Physical therapy. This helps you regain strength and movement and can reduce pain. It includes exercises, stretching, and using heat or cold.

- Scar massage. This involves gently rubbing the surgical scar to make it softer, more flexible and less sensitive. This can help with tightness, itching and overall comfort. It works by improving blood flow and breaking down stiff scar tissue.

- Medicines. These include those for nerve pain target pain coming from damaged nerves. Common examples include gabapentin and pregabalin, as well as certain antidepressants such as amitriptyline or duloxetine. Topical creams or patches with pain-relieving ingredients also can be used.

- Nerve blocks. These involve injecting numbing medicine near specific nerves to stop pain signals from reaching your brain. This can be very effective for headaches and other pain in the head and scalp.

- Removing hardware if it's the cause of pain. Though rare, the metal plates and screws used to put your skull back together after surgery can cause pain. If this is the case, removing these hardware pieces can help relieve the pain.

Other long-term side effects of craniotomy vary from person to person and depend on the type of surgery and recovery.

- Headache or sensitivity. Some people have ongoing headaches or a tight or odd feeling at the surgery site. This may be related to scarring, nerve irritation or changes in fluid pressure. In some cases, the discomfort can last for months or even years.

- Scalp or bone flap pain. Some people report long-term soreness or sharp pain near the incision. This can be caused by trapped nerves, tight scalp muscles, or sensitivity from plates or screws. When nerves are involved, this is called neuropathic pain.

- Numbness or tingling. Numbness around the incision is common, especially near the forehead, temple or behind the ear. It often fades with time but sometimes can last or feel unusual when touched.

- Seizures. Some people develop seizures after surgery, especially if brain tissue was affected. Long-term use of seizure medicines may be needed.

- Cognitive or emotional changes. Changes in memory, attention, mood or personality may occur if certain areas of the brain were involved. Fatigue or slower thinking can also happen during recovery.

- Infection or poor bone healing. Rarely, the bone flap doesn't heal well or becomes infected. This may require another surgery. Hardware used during the surgery also can shift or cause discomfort in some people.

Oct. 02, 2025