Overview

Functions of the brain

Functions of the brain

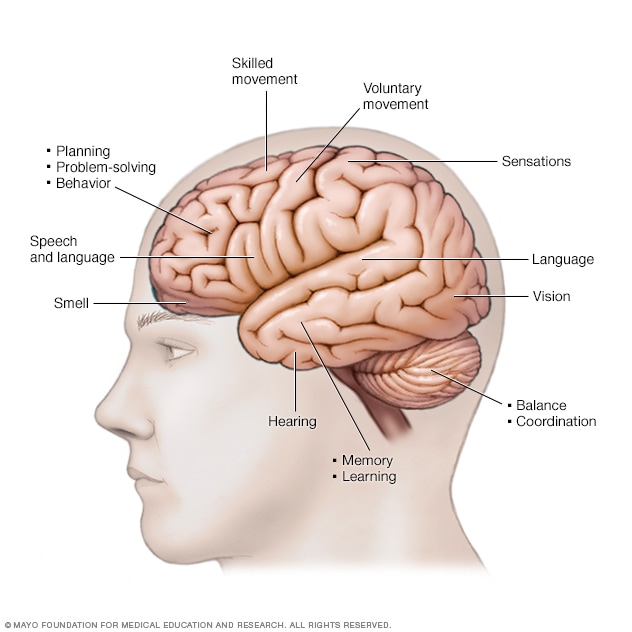

Different areas of the brain are responsible for different vital functions.

Primary progressive aphasia (uh-FAY-zhuh) is a rare nervous system condition that affects a person's ability to communicate. People who have primary progressive aphasia can have trouble expressing their thoughts and understanding or finding words.

Symptoms develop gradually, often before age 65. They get worse over time. People with primary progressive aphasia can lose the ability to speak and write. Eventually they're not able to understand written or spoken language.

This condition progresses slowly. People who have primary progressive aphasia may continue caring for themselves and participating in daily activities for several years.

Primary progressive aphasia is a type of frontotemporal dementia. Frontotemporal dementia is a cluster of conditions that result from the degeneration of the frontal or temporal lobes of the brain. These areas include brain tissue involved in speech and language. Not all people with primary progressive aphasia have dementia, but most develop it. The term "dementia" is typically not used until a person can't do things alone due to changes in their thinking and understanding.

Products & Services

Symptoms

Primary progressive aphasia symptoms vary based on which part of the brain's language areas are involved. The condition has three types. Each type causes different symptoms. Symptoms develop over time and gradually get worse.

Semantic variant primary progressive aphasia

Symptoms include:

- Trouble understanding spoken or written language, particularly single words.

- Trouble understanding the meaning of words.

- Not being able to name objects.

- Trouble spelling words, especially those that aren't spelled the way that they sound, such as the word "yacht."

Logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia

Symptoms include:

- Trouble understanding spoken language, particularly long sentences.

- Pausing and hesitating to search for words while speaking.

- Not being able to repeat phrases or sentences.

Nonfluent-agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia

Symptoms include:

- Leaving out words or putting words in the wrong order in written and spoken language.

- Trouble understanding complex sentences.

- Trouble speaking. This includes making errors in speech sounds, known as apraxia of speech.

Primary progressive apraxia of speech is related to primary progressive aphasia. However, people with this condition don't have trouble with language. They have problems speaking. This includes making errors in speech sounds or having trouble saying words quickly.

When to see a doctor

See your healthcare professional if you have concerns about your ability to communicate. If you have a family member or friend who has symptoms of primary progressive aphasia, talk to the person about your concerns. Offer to go with the person to see a healthcare professional.

If changes in speech or communication come on suddenly, call 911 or your local emergency number.

Causes

Primary progressive aphasia is caused by a shrinking of certain areas of the brain, known as lobes. In primary progressive aphasia, the frontal, temporal or parietal lobes are affected. When areas of the brain shrink, it's called atrophy. The atrophy caused by primary progressive aphasia mainly happens on the left side of the brain. The areas affected are responsible for speech and language.

Atrophy is linked to the presence of certain proteins in the brain. The proteins may reduce brain activity or function.

Risk factors

Risk factors for primary progressive aphasia include:

- Learning disabilities. People who had a childhood learning disability such as dyslexia may have a higher risk of developing primary progressive aphasia.

- Certain gene changes. Although primary progressive aphasia most often happens randomly, rare gene changes have been linked to the condition. If other members of your family have had primary progressive aphasia, consider genetic testing to see if you are more likely to develop it.

Complications

People with primary progressive aphasia eventually lose the ability to speak and write. This may take anywhere from 3 to 15 years. People with the condition also have trouble understanding written and spoken language.

As the disease progresses, other mental skills such as memory, planning and organizing can be affected. Some people develop other symptoms such as problems with movement, balance and swallowing. With these complications, people with the disease eventually need help with day-to-day care.

People with primary progressive aphasia also can develop depression as the disease progresses. Other complications might include blunted emotions such as not showing concern, poor judgment or social behavior that's not appropriate.

Prevention

There is no known way to prevent primary progressive aphasia. However, you can keep your brain healthy by using GROWTH:

- Get quality sleep.

- Reduce stress.

- Open connections.

- Work out.

- Try new things.

- Healthy eating.

Feb. 07, 2025