Overview

Moyamoya disease

Moyamoya disease

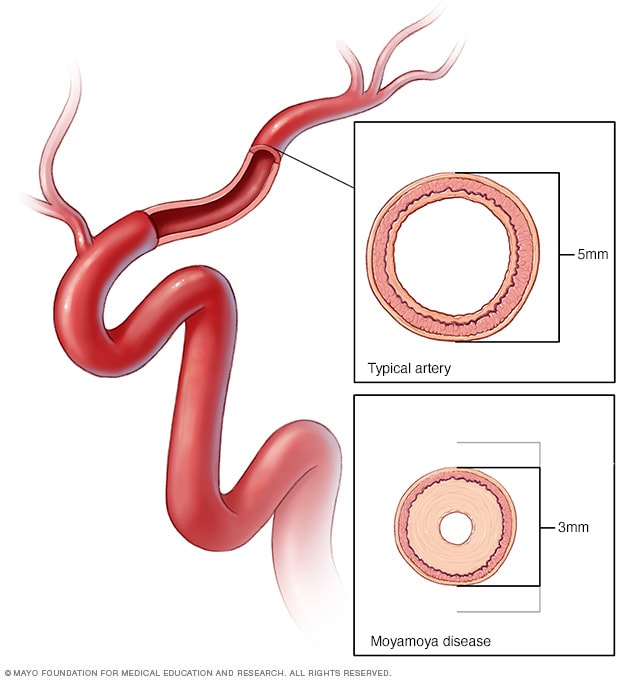

In moyamoya disease, arteries to the brain become narrow and may even close, leading to reduced delivery of oxygen-rich blood to the brain. This lack of blood flow to the brain can cause a stroke and other symptoms.

Moyamoya disease is a rare blood vessel condition in which the carotid artery in the skull becomes blocked or narrowed. The carotid artery is a major artery that brings blood to the brain. When it's blocked, blood flow to the brain is reduced. Tiny blood vessels then form at the base of the brain to supply the brain with blood.

The condition may cause a ministroke, known as a transient ischemic attack (TIA), or a stroke. It also can cause bleeding in the brain. Moyamoya disease can affect how well the brain functions and can cause cognitive and developmental delays or disability.

Moyamoya disease most commonly affects children. However, adults may have the condition as well. Moyamoya disease is found all over the world. But it's more common in East Asian countries, especially Korea, Japan and China. This may be due to certain genetic factors in those populations.

Products & Services

Symptoms

Moyamoya disease may happen at any age. But symptoms are most common in children between ages 5 and 10 and in adults between ages 30 and 50. Spotting symptoms early is very important to prevent complications such as a stroke.

Moyamoya disease causes different symptoms in adults and children. In children, the first symptom is usually a stroke or recurrent transient ischemic attack, also called TIA. Adults may experience these symptoms, as well. But adults also may experience bleeding in the brain, known as a hemorrhagic stroke. The bleeding happens because of the way blood vessels in the brain formed.

Symptoms of moyamoya disease related to reduced blood flow to the brain include:

- Headache.

- Seizures.

- Weakness, numbness or paralysis in the face, arm or leg. This is typically on one side of the body.

- Vision problems.

- Trouble speaking or understanding others, known as aphasia.

- Cognitive or developmental delays.

- Involuntary movements.

These symptoms can be triggered by exercise, crying, coughing, straining or a fever.

See your healthcare professional if you have any of the symptoms of moyamoya disease. Early detection and treatment can help prevent a stroke and serious complications.

When to see a doctor

Seek immediate medical attention if you notice any symptoms of a stroke or ministroke, even if the symptoms seem to come and go or disappear.

To check for signs of stroke, think "FAST" and do the following:

- Face. Ask the person to smile. Does one side of the face droop?

- Arms. Ask the person to raise both arms. Does one arm drift downward? Or is one arm unable to rise up?

- Speech. Ask the person to repeat a simple phrase. Is the person's speech slurred or strange?

- Time. If you observe any of these signs, call 911 or emergency medical help right away.

Don't wait to see if symptoms go away. Every minute counts. The longer a stroke goes untreated, the greater the potential for brain damage and disability.

If you're with someone you suspect is having a stroke, watch the person carefully while waiting for emergency assistance.

Causes

The exact cause of moyamoya disease isn't known. Moyamoya disease is most commonly seen in Japan, Korea and China. But it also happens in other parts of the world. Because moyamoya disease is most common in these Asian countries, researchers believe this strongly suggests a genetic factor in some populations.

Sometimes changes to the blood vessels, known as vascular changes, can happen that mimic moyamoya disease. These changes may have different causes and symptoms. This is known as moyamoya syndrome.

Moyamoya syndrome can be linked to certain conditions, such as Down syndrome, sickle cell anemia, neurofibromatosis type 1 and hyperthyroidism.

Risk factors

Though the cause of moyamoya disease is not known, certain factors may increase your risk of having the condition. They include:

- Asian heritage. Although moyamoya disease is found all over the world, it's more common in East Asian countries, especially Korea, Japan and China. This may be due to certain genetic factors in those populations. People with Asian heritage living in Western countries also have a higher risk of moyamoya disease.

- Family history of moyamoya disease. If you have a family member with moyamoya disease, your risk of having the condition is 30 to 40 times higher than that of the general population. This strongly suggests a genetic link.

- Medical conditions. Moyamoya syndrome sometimes happens with other disorders, including neurofibromatosis type 1, sickle cell disease and Down syndrome, among many others.

- Being female. Moyamoya disease is slightly more common in females.

- Being young. Though adults can have moyamoya disease, children younger than 15 years old are most commonly affected.

Complications

Most complications from moyamoya disease are linked to the effects of strokes. They include seizures, paralysis and vision problems. Other complications include speech problems, movement disorders and developmental delays. Moyamoya disease can cause serious and permanent damage to the brain.

Prevention

There is no way to prevent moyamoya disease. However, moyamoya treatments can prevent strokes and other complications.