Overview

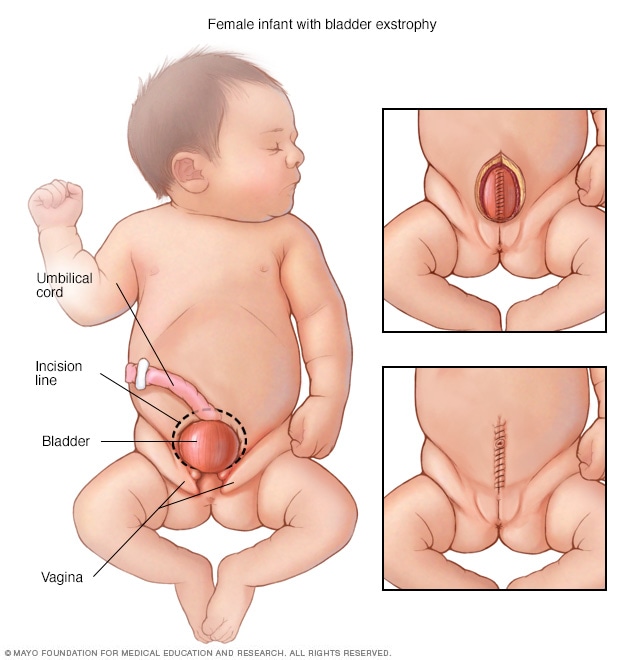

Bladder exstrophy in a female infant

Bladder exstrophy in a female infant

In girls born with bladder exstrophy, the bladder is on the outside of the body and the vagina is not fully formed. Surgeons close the bladder (top right) and then close the abdomen and skin (bottom right).

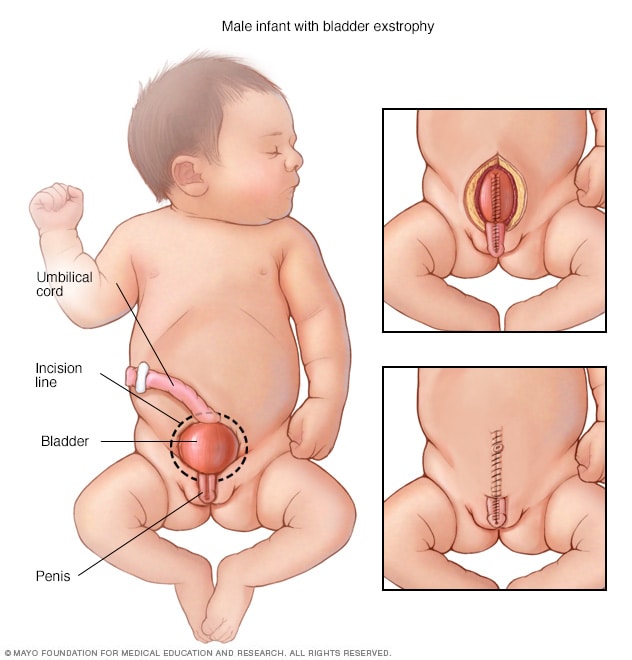

Bladder exstrophy in a male infant

Bladder exstrophy in a male infant

In boys born with bladder exstrophy, the bladder is on the outside of the body. The penis and the urine tube, called the urethra, are not fully closed. Surgeons close the penis and bladder (top right) and then close the abdomen and skin (bottom right).

Bladder exstrophy (EK-stroh-fee) is a rare condition present at birth. During pregnancy, the bladder of an unborn baby, also called a fetus, forms outside of the stomach area. This area also is called the abdomen. The exposed bladder can't store urine or work as it should. This causes the baby to leak urine after being born.

Bladder exstrophy also can affect the genitals, stomach muscles, pelvic bones, intestines and reproductive organs. The cause of the condition isn't clear, but genes may play a role.

Bladder exstrophy may be spotted on a routine ultrasound during pregnancy. But sometimes, the condition can't be seen until the baby is born. A baby born with bladder exstrophy needs surgery to close the bladder and repair other affected body parts as needed.

Products & Services

Symptoms

Bladder exstrophy can involve a spectrum of symptoms. The symptoms depend on which body parts are affected along with the bladder and stomach area, and how serious the effects are. Bladder exstrophy is the most common in a larger group of conditions present at birth called the bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex (BEEC). Children with BEEC have one of the following:

- Epispadias. This is the least serious form of BEEC. With an epispadias (ep-ih-SPAY-dee-us), the tube through which urine leaves the body doesn't fully develop. This tube is called the urethra.

-

Bladder exstrophy. This condition causes the bladder to form on the outside of the body. The bladder also is turned inside out. Usually, bladder exstrophy involves organs of the urinary tract, as well as the digestive and reproductive systems. Changes in the abdominal wall, bladder, genitals and pelvic bones can happen. So can changes in the end part of the large intestine called the rectum and the opening at the end of the rectum called the anus.

Children with bladder exstrophy also have a condition that causes urine to flow the wrong way. This is called vesicoureteral reflux. Urine flows backward from the bladder into tubes called ureters that connect to the kidneys. Children with bladder exstrophy have epispadias as well.

-

Cloacal exstrophy. Cloacal exstrophy (kloe-AY-kul EK-stroh-fee) is the most serious form of BEEC. In this condition, the bladder and intestine are exposed. The anus may not open and the intestine may be short. The penis or the vagina may be split. The pelvic bones are affected as well.

The kidneys, backbone and spinal cord also may be affected. Most children with cloacal exstrophy have spinal conditions, including spina bifida. Children born with protruding abdominal organs probably also have cloacal exstrophy or bladder exstrophy.

Causes

The cause of bladder exstrophy isn't known. But researchers think that genetic factors likely play a role.

What's known is that during pregnancy, a tissue called the cloaca (klo-AY-kuh) typically covers the wall of the unborn baby's lower stomach. Later, it's replaced by stomach muscles. But if the cloaca bursts before the stomach muscles form, bladder exstrophy may develop.

Risk factors

Factors that raise the risk of bladder exstrophy include:

- Family history. Firstborn children, children of a parent with bladder exstrophy or siblings of a child with bladder exstrophy have a higher chance of being born with the condition.

- Race. Bladder exstrophy is more common in white babies than in Black or Hispanic babies.

- Male sex. More boys than girls are born with bladder exstrophy.

- Use of assisted reproduction to become pregnant. Children born through fertility treatments known as assisted reproductive technologies have a higher risk of bladder exstrophy. These treatments include in vitro fertilization.

Complications

Bladder exstrophy can lead to other health conditions called complications.

Without surgery

Without treatment, children with bladder exstrophy won't be able to hold urine. This is called urinary incontinence. These children also are at risk of having trouble with sexual function later in life. They have a higher risk of bladder cancer as well.

After surgery

Surgery can lower the chances of some complications. The success of surgery depends on how serious the condition is. Many children who have surgical repair are able to hold urine. Young children with bladder exstrophy may walk with their legs turned somewhat outward. This is due to the separation of their pelvic bones. Walking gets better with age.

Long-term complications

People born with bladder exstrophy can go on to have regular sexual function. That includes being able to have children. But pregnancy often is high risk for a pregnant person who's had bladder exstrophy and for the unborn baby. A planned cesarean birth, also known as a C-section, may be needed.

Jan. 28, 2025