Overview

Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer

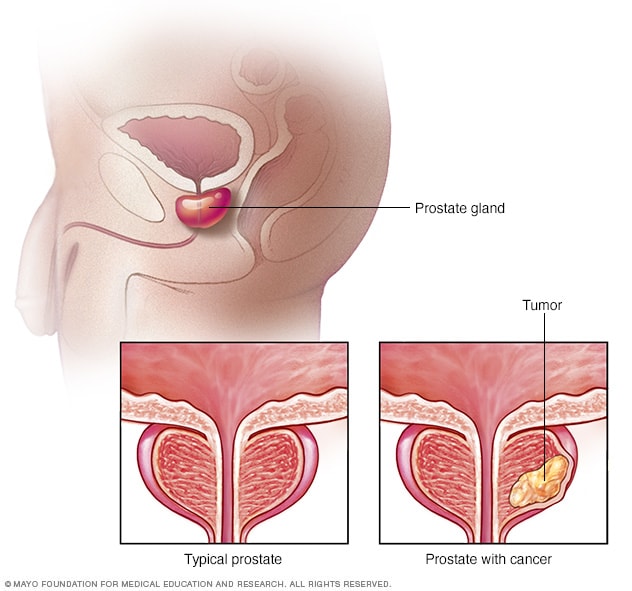

Prostate cancer is a growth of cells that starts in the prostate. The prostate is a small gland that helps make semen. It's part of the male reproductive system. This illustration shows a typical prostate gland and a prostate gland with cancer.

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer is a treatment that lowers or blocks testosterone. This treatment also is called androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

Most prostate cancer cells need testosterone to grow. ADT stops testosterone from being made or from reaching prostate cancer cells. This causes prostate cancer cells to die or to grow more slowly.

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer may involve medicines or, in rare cases, surgery to remove the testicles.

Types

Types of hormone therapy for prostate cancer include:

- Medicines that stop the body from making testosterone. Some medicines block signals that tell the testicles to make testosterone. These medicines are called luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists and antagonists. Another name for them is gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and antagonists.

- Medicines that block the action of testosterone in the body. These medicines are known as antiandrogens. They're often used with LHRH agonists. That's because LHRH agonists can cause a brief rise in testosterone levels before testosterone levels go down.

- Surgery to remove the testicles. This surgery is called an orchiectomy. It lowers testosterone levels in the body quickly. In some cases, only the part of the testicles that makes testosterone is removed. Both procedures are permanent.

In the form of medicine, hormone therapy for prostate cancer, also called ADT, can be given all the time or off and on:

- Continuous ADT is given without stopping.

- Intermittent ADT is given for a set amount of time or until a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test shows a low number. This test measures a protein produced by both cancerous and noncancerous tissue in the prostate. If the number is low, the treatment is paused. If the cancer comes back or gets worse, the treatment may start again.

Some early studies show that intermittent ADT may cause fewer side effects and still work just as well as continuous ADT for some people. It also might help them feel better day to day.

Products & Services

Why it's done

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer is used to block the hormone testosterone in the body. Testosterone fuels the growth of prostate cancer cells.

Hormone therapy can help shrink cancer and slow the growth of cancer. But hormone therapy on its own is not a cure for prostate cancer.

Hormone therapy usually is the first treatment choice for advanced prostate cancer. It typically is not used by itself to treat early-stage prostate cancer. Hormone therapy might be used in combination with other treatments. These treatments might include radiation therapy, freezing the cancer cells with very cold liquid, called cryotherapy, or a targeted therapy called a PARP inhibitor. A PARP inhibitor is another term for poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor.

Hormone therapy might be a choice at different times and for different reasons during prostate cancer treatment. Examples include:

- For prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, called metastatic prostate cancer, to shrink the cancer and slow the growth of tumors. The treatment also might ease symptoms.

- For prostate cancer that has spread to nearby tissues, to make radiation therapy better at lowering the risk of the cancer coming back.

- After prostate cancer treatment if prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test levels stay high or rise.

- To lower the risk that the cancer will come back in those who have a high risk of cancer recurrence.

Risks

Side effects of hormone therapy for prostate cancer can include:

- Loss of muscle, bone thinning, also called osteoporosis, and bone breaks.

- Increased body fat and weight gain.

- Loss of sex drive and not being able to get or keep an erection, called erectile dysfunction.

- Hot flashes.

- Less body hair, smaller genitals and growth of breast tissue.

- Tiredness.

- Mood changes, such as anxiety and depression, which may include a sense of apathy.

- Diabetes and heart disease.

How you prepare

Talk about your options with your oncologist

Before you begin treatment, you'll meet with a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating cancer, called an oncologist. If you're thinking of having hormone therapy for prostate cancer, talk about your choices with the oncologist. Prepare for this meeting by creating a list of questions to ask.

Questions about why hormone therapy is recommended:

- What are my treatment options?

- Do I need hormone therapy? If so, what are the reasons you recommend hormone therapy for me?

- What are the possible benefits of hormone therapy for my specific situation?

- What types of hormone therapy do you offer, and which do you recommend?

- How long is hormone therapy likely to work for me? What options will I have if it stops working?

- Are there other treatment choices that I should think about?

Questions about risks:

- What are the possible risks and side effects of hormone therapy? Which ones are most common?

- How could hormone therapy affect my daily life, including my routine, activities, sexual health, energy levels and emotions?

- Are there lifestyle approaches or medical treatments I can use to reduce the risks and side effects?

- How will you check on and treat side effects during treatment?

Questions about treatment expectations:

- How is the hormone therapy given — is it a pill, injection, implant or surgery?

- How will you check to see how well treatment is working? What tests will I need?

- How long will I need to continue hormone therapy?

- Is there a diet or exercise plan I need to follow during treatment?

- Will I need to make any changes at work or at home during hormone therapy?

- Where can I find support groups or counseling to help cope with the emotional parts of treatment?

What you can expect

GnRH and LHRH agonists and antagonists

These medicines stop the testicles from making testosterone.

Most of these medicines are given as a shot, also called an injection. The shots go under the skin or into a muscle. Depending on the medicine used, the shots might be given monthly, every few months or several months apart.

Some of these medicines can be put under the skin as an implant. The implant slowly releases medicine over time.

GnRH and LHRH agonists include:

- Leuprolide (Eligard, Lupron Depot, others).

- Goserelin (Zoladex).

- Triptorelin (Triptodur, Trelstar).

GnRH and LHRH antagonists include:

- Degarelix (Firmagon).

- Relugolix (Orgovyx).

For a few weeks after an LHRH agonist, testosterone levels might rise briefly. This is called a flare. GnRH and LHRH antagonists don't cause a flare.

A testosterone flare can make cancer symptoms worse. For people at high risk of a flare affecting their symptoms, early use of a GnRH antagonist or antiandrogen can reduce the risk.

Antiandrogens

Antiandrogens block the actions of testosterone in the body. Newer forms of antiandrogen medicines are sometimes called androgen receptor pathway inhibitors (ARPIs) or androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSIs). Antiandrogens can be taken as a pill.

Options may include:

- Apalutamide (Erleada).

- Darolutamide (Nubeqa).

- Enzalutamide (Xtandi).

- Abiraterone (Yonsa, Zytiga), which is often used with prednisone.

Orchiectomy

This surgery to remove the testicles is rarely used. After numbing the groin area, a surgeon cuts into the groin and takes out the testicle through the opening. The surgeon repeats the process for the other testicle. In some cases, only the part of the testicles that makes testosterone is removed.

All surgery carries a risk of pain, bleeding and infection. Most people can go home after this operation. It usually doesn't require staying in the hospital.

Results

If you get hormone therapy, also called androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), for prostate cancer, you'll need to see your healthcare professional regularly. You'll likely be asked about any side effects you might have. You can treat some side effects with medicine. Doing exercise also can help if you lose muscle, have weaker bones, gain weight or feel tired.

Hormone therapy resistance

Over time, most prostate cancers eventually become resistant to ADT. This means the hormone therapy stops working. The cancer continues to grow even when testosterone levels are very low. You might hear this type of cancer called castration resistant, hormone resistant or androgen resistant. You also might hear it called hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC).

It's difficult to predict how long until a prostate cancer becomes resistant to ADT. About half of those treated with ADT become resistant within 2 to 3 years. And about half become resistant after more than 2 to 3 years.

Your healthcare professional likely will order regular testing to check your health and to see if the cancer is coming back or getting worse. These tests can show your response to ADT.

If your cancer appears to become resistant, you generally continue taking hormone therapy. This is to keep testosterone levels low. If testosterone levels go up, it could make the cancer grow or get worse.

A healthcare professional may suggest a different hormone therapy. Or you might also be given another type of medicine, depending on your situation. Other medicines could include:

- Chemotherapy.

- A type of medicine that contains radioactive material, called a radiopharmaceutical.

- A type of medicine called a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor. This could be an option if you have certain gene changes.

- A type of medicine that targets your immune system, called immunotherapy. This might be an option if you have a certain type of tumor.

Survival rates

How long someone lives with prostate cancer after starting hormone therapy can be different for each person. It depends on things like the stage of the cancer and how far it has spread. Your healthcare professional may be able to give you more exact information based on your condition.