Diagnosis

Colonoscopy exam

Colonoscopy exam

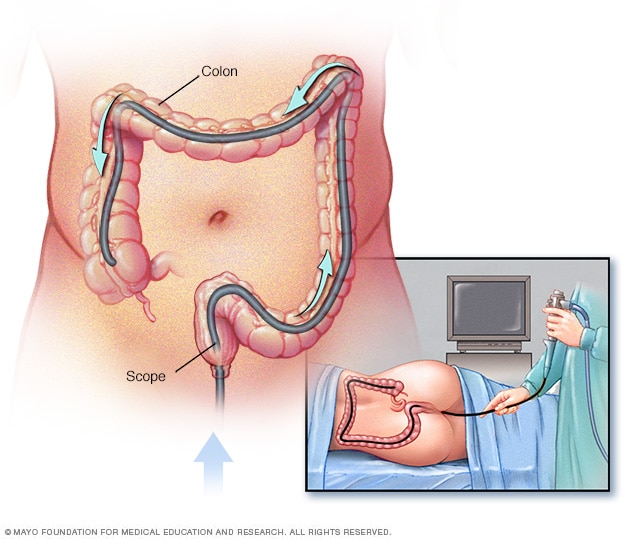

During a colonoscopy, a healthcare professional puts a colonoscope into the rectum to check the entire colon.

Rectal cancer diagnosis often begins with an imaging test to look at the rectum. A thin, flexible tube with a camera may be passed into the rectum and colon. A sample of tissue may be taken for lab testing.

Rectal cancer can be found during a screening test for colorectal cancer. Or it may be suspected based on your symptoms. Tests and procedures used to confirm the diagnosis include:

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is a test to look at the colon and rectum. It uses a long, flexible tube with a camera at the end, called a colonoscope, to show the colon and rectum. Your healthcare professional looks for signs of cancer. Medicines are given before and during the procedure to keep you comfortable.

Biopsy

A biopsy is a procedure to remove a sample of tissue for testing in a lab. To get the tissue sample, a healthcare professional passes special cutting tools through a colonoscope. The health professional uses the tools to remove a very small sample of tissue from inside the rectum. The tissue sample is sent to a lab to look for cancer cells.

Other special tests give more details about the cancer cells. Your healthcare team uses this information to make a treatment plan.

Tests to look for rectal cancer spread

If you're diagnosed with rectal cancer, the next step is to determine the cancer's extent, called the stage. Your healthcare team uses the cancer staging test results to help create your treatment plan.

Staging tests include:

- Complete blood count (CBC). A CBC reports the numbers of different types of cells in the blood. A CBC shows whether your red blood cell count is low, called anemia. Anemia suggests that the cancer is causing blood loss. A high level of white blood cells is a sign of infection. Infection is a risk if a rectal cancer grows through the wall of the rectum.

- Blood tests to measure organ function. A chemistry panel is a blood test to measure levels of different chemicals in the blood. Worrying levels of some of these chemicals may suggest that cancer has spread to the liver. High levels of other chemicals could mean problems with other organs, such as the kidneys and liver.

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Cancers sometimes produce substances called tumor markers. These tumor markers can be detected in blood. One such marker is CEA. CEA may be higher than usual in people with colorectal cancer. CEA testing can be helpful in monitoring your response to treatment.

- CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. This imaging test helps determine whether rectal cancer has spread to other organs, such as the liver or lungs.

- MRI of the pelvis. An MRI provides a detailed image of the muscles, organs and other tissues surrounding cancer in the rectum. An MRI also shows the lymph nodes near the rectum and different layers of tissue in the rectal wall more clearly than a CT does.

- Surgery. Surgery may be used in rectal cancer staging when doctors or other healthcare professionals need to confirm how far the cancer has spread, especially after treatment such as radiation or chemotherapy. By examining the tumor and nearby lymph nodes removed during surgery, they can determine the exact stage of the cancer, including whether it has spread beyond the rectum or to lymph nodes.

More Information

Treatment

Rectal cancer is often curable, especially when found early. Even some cancers that have spread may be curable with the right treatment approach. Treatment may begin with surgery to remove the cancer. If the cancer grows larger or spreads to other parts of the body, treatment might start with medicine and radiation instead.

Your healthcare team considers many factors when creating a treatment plan. These factors may include your overall health, the type and stage of your cancer, and your preferences.

Surgery

Surgery to remove the cancer can be used alone or in combination with other treatments.

Procedures used for rectal cancer may include:

-

Removing very small cancers from the inside of the rectum. Very small rectal cancers may be removed using a colonoscope or another specialized type of scope inserted through the anus. This procedure is called transanal local excision. Surgical tools can be passed through the scope to cut away the cancer and some of the healthy tissue around it.

This procedure might be an option if your cancer is small and not likely to spread to nearby lymph nodes. If a lab exam of your cancer cells shows that they are aggressive or more likely to spread to the lymph nodes, additional surgery may be needed.

-

Removing all or part of the rectum. Larger rectal cancers that are far enough away from the anus might be removed in a procedure that removes all or part of the rectum. This procedure is called low anterior resection. Nearby tissue and lymph nodes also are removed. This procedure preserves the anus so that waste can leave the body as it usually would.

How the procedure is performed depends on the cancer's location. If cancer affects the upper portion of the rectum, that part of the rectum is removed. The colon is then attached to the remaining rectum. This is called colorectal anastomosis. All of the rectum may be removed if the cancer is in the lower portion of the rectum. Then the colon is shaped into a pouch and attached to the anus, called coloanal anastomosis.

-

Removing the rectum and anus. For rectal cancers that are located near the anus, it might not be possible to remove the cancer completely without hurting the muscles that control bowel movements. In these situations, surgeons may recommend an operation called abdominoperineal resection, also known as APR. With APR, the rectum, anus and some of the colon are removed, as well as nearby tissue and lymph nodes.

The surgeon creates an opening in the abdomen and attaches the remaining colon. This is called a colostomy. Waste leaves the body through the opening and collects in a bag that attaches to the abdomen.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy treats cancer with strong medicines. Chemotherapy medicines are typically used before or after surgery in people with rectal cancer. Chemotherapy is often combined with radiation therapy and used before an operation to shrink a large cancer so that it's easier to remove with surgery.

In people with advanced cancer that has spread beyond the rectum, chemotherapy is used to slow down the growth of cancer. This extends survival and helps relieve symptoms caused by the cancer.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy treats cancer with powerful energy beams. The energy can come from X-rays, protons or other sources. For rectal cancer, radiation therapy is most often done with a procedure called external beam radiation. During this treatment, you lie on a table while a machine moves around you. The machine directs radiation to precise points on your body.

In people with rectal cancer, radiation therapy is often combined with chemotherapy. It is usually used before surgery to shrink a cancer to make it easier to remove.

When surgery isn't an option, radiation therapy might be used to relieve symptoms, such as bleeding and pain.

Combined chemotherapy and radiation

Combining chemotherapy and radiation therapy may enhance the effectiveness of each treatment. Combined chemotherapy and radiation may be the only treatment you receive, or combined therapy can be used before surgery. Combining chemotherapy and radiation treatments may increase side effects.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy for cancer is a treatment that uses medicines that attack specific chemicals in the cancer cells. By blocking these chemicals, targeted treatments can cause cancer cells to die.

For rectal cancer, targeted therapy may be combined with chemotherapy for advanced cancers that can't be removed with surgery or for cancers that come back after treatment.

Some targeted therapies only work in people whose cancer cells have certain DNA changes. Your cancer cells may be tested in a lab to see if these medicines might help you.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy for cancer is a treatment with medicine that helps the body's immune system kill cancer cells. The immune system fights off diseases by attacking germs and other cells that shouldn't be in the body. Cancer cells survive by hiding from the immune system. Immunotherapy helps the immune system cells find and kill the cancer cells.

For rectal cancer, immunotherapy is sometimes used before or after surgery. It also may be used for advanced cancers that have spread to other parts of the body. Immunotherapy only works for a small number of people with rectal cancer. Special testing can determine if immunotherapy might work for you.

Palliative care

Palliative care is a special type of healthcare that helps you feel better when you have a serious illness. If you have cancer, palliative care can help relieve pain and other symptoms. A healthcare team that may include doctors, nurses and other specially trained health professionals provides palliative care. The care team's goal is to improve quality of life for you and your family.

Palliative care specialists work with you, your family and your care team. They provide an extra layer of support while you have cancer treatment. You can have palliative care at the same time you're getting strong cancer treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

The use of palliative care with other proper treatments can help people with cancer feel better and live longer.

More Information

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Coping and support

With time, you'll find what helps you cope with the uncertainty and worry of a rectal cancer diagnosis. Until then, you may find it helps to:

Learn enough about rectal cancer to make decisions about your care

Ask your healthcare team about your cancer, including your test results, treatment options and, if you like, your prognosis. As you learn more about rectal cancer, you may become more confident in making treatment decisions.

Keep friends and family close

Keeping your close relationships strong can help you deal with rectal cancer. Friends and family can provide the practical support you may need, such as helping take care of your home if you're in the hospital. And they can serve as emotional support when you feel overwhelmed by having cancer.

Find someone to talk with

Find someone who is willing to listen to you talk about your hopes and worries. This may be a friend or family member. The concern and understanding of a counselor, medical social worker, clergy member or cancer support group also may be helpful.

Ask your healthcare team about support groups in your area. Other sources of information include the U.S. National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society.

Preparing for your appointment

Make an appointment with a doctor or other healthcare professional if you have any symptoms that worry you.

If your healthcare professional thinks you might have rectal cancer, you may be referred to a doctor who specializes in treating diseases and conditions of the digestive system, called a gastroenterologist. If a cancer diagnosis is made, you also may be referred to a doctor who specializes in treating cancer, called an oncologist.

Because appointments can be brief, it's a good idea to be prepared. Here's some information to help you get ready.

What you can do

- Be aware of any pre-appointment restrictions. At the time you make the appointment, be sure to ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as restrict your diet.

- Write down symptoms you have, including any that may not seem related to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment.

- Write down key personal information, including major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins or supplements you're taking and the doses.

- Take a family member or friend along. Sometimes it can be very hard to remember all the information provided during an appointment. Someone who goes with you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

- Write down questions to ask your healthcare team.

Your time with your healthcare team is limited, so preparing a list of questions can help you make the most of your time together. List your questions from most important to least important in case time runs out. For rectal cancer, some basic questions to ask include:

- In what part of the rectum is my cancer located?

- What is the stage of my rectal cancer?

- Has my rectal cancer spread to other parts of my body?

- Will I need more tests?

- What are the treatment options?

- How much does each treatment increase my chances of a cure?

- What are the potential side effects of each treatment?

- How will each treatment affect my daily life?

- Is there one treatment option you believe is the best?

- What would you recommend to a friend or family member in my situation?

- Should I see a specialist?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can take with me? What websites do you recommend?

- What will determine whether I should plan for a follow-up visit?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Be prepared to answer questions, such as:

- When did your symptoms begin?

- Have your symptoms been continuous or occasional?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your symptoms?

Sept. 12, 2025