Diagnosis

Pancreatic cancer FAQs

Get answers to the most frequently asked questions about pancreatic cancer from Mayo Clinic surgical oncologist Chee-Chee Stucky, M.D.

Hi. I'm Dr. Chee-Chee Stucky, a surgical oncologist at Mayo Clinic, and I'm here to answer some of the important questions you might have about pancreatic cancer.

Is pancreatic cancer preventable?

Technically, no. There are some risk factors associated with pancreatic cancer, like smoking and obesity. Those are both modifiable risk factors. So the healthier you are, the less risk you might have of pancreatic cancer. But ultimately if you have a pancreas, there's always a risk of developing pancreatic cancer.

Do all pancreatic cysts become cancerous?

The short answer is no. The vast majority of pancreatic cysts will not become cancerous. There are a few, but I would recommend asking your doctor about those.

How are breast cancer and pancreatic cancer connected?

The connection between breast cancer and pancreatic cancer is a genetic mutation called BRCA. So anybody who might have a newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer, but a family history of breast cancer, should definitely undergo genetic testing in order to see if there is a mutation present. If so, the rest of the family needs to undergo screening and possibly genetic testing with the hopes of potentially identifying cancer at an earlier stage.

What is the Whipple procedure?

The Whipple procedure is one of the most common procedures we do for pancreatic cancer, Specifically when located in the head or uncinate process of the pancreas. Because of where that tumor is located, we also have to remove everything that's connected to the pancreas, specifically the duodenum and the bile duct, as well as the surrounding lymph nodes. Once it's all removed, then we need to put everything back together, which includes the biliary tract, the pancreatic duct, and the GI tract.

Can you live without a pancreas?

You can definitely live without a pancreas. You will have diabetes. But fortunately with our new technologies, insulin pumps are much improved. And therefore, patients still have a good quality of life.

How can I be the best partner to my medical team?

You can be the best partner to your medical team by staying healthy, staying informed, ask a lot of questions and bring somebody with you to your appointments so they can be an additional set of eyes and ears. Never hesitate to ask your medical team any questions or concerns you have. Being informed makes all the difference. Thanks for your time and we wish you well.

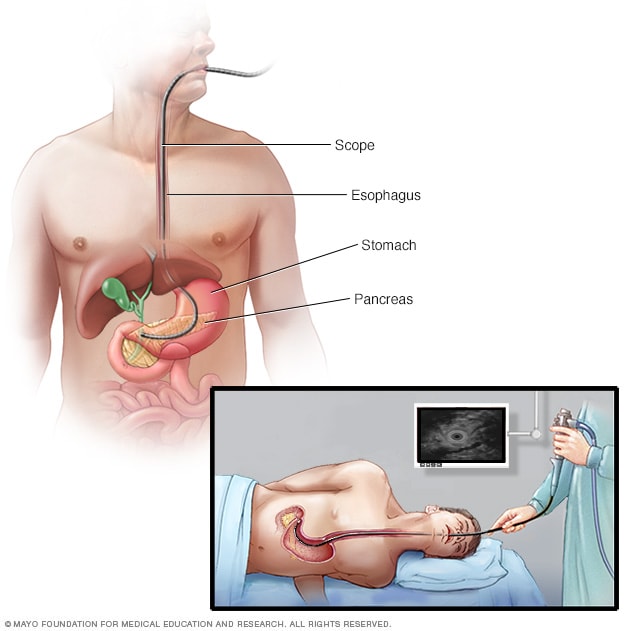

Pancreatic ultrasound

Pancreatic ultrasound

During an endoscopic ultrasound of the pancreas, a thin, flexible tube called an endoscope is inserted down the throat and into the chest. An ultrasound device at the end of the tube emits sound waves that generate images of the digestive tract and nearby organs and tissues.

Tests used to diagnose pancreatic cancer include:

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests take pictures that show the inside of the body. Imaging tests used to diagnose pancreatic cancer include ultrasound, CT scans, MRI scans and, sometimes, positron emission tomography scans, also called PET scans.

- A scope with ultrasound. Endoscopic ultrasound, also called EUS, is a test to make pictures of the digestive tract and nearby organs and tissues. EUS uses a long, thin tube with a camera, called an endoscope. The endoscope passes down the throat and into the stomach. An ultrasound device on the endoscope uses sound waves to create images of nearby tissues. It can be used to make pictures of the pancreas.

Removing a tissue sample for testing. A biopsy is a procedure to remove a small sample of tissue for testing in a lab. Most often, a health professional gets the sample during EUS. During EUS, special tools are passed through the endoscope to take some tissue from the pancreas. Less often, a sample of tissue is collected from the pancreas by inserting a needle through the skin and into the pancreas. This is called fine-needle aspiration.

The sample goes to the lab for testing to see if its cancer. Other specialized tests can show what DNA changes are present in the cancer cells. The results help your health care team create your treatment plan.

- Blood tests. Blood tests might show proteins called tumor markers that pancreatic cancer cells make. One tumor marker test used in pancreatic cancer is called CA19-9. Doctors often repeat this test during and after treatment to understand how the cancer is responding. Some pancreatic cancers don't make extra CA19-9, so this test isn't helpful for everyone.

- Genetic testing. If you're diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, talk with your health care team about genetic testing. Genetic testing uses a sample of blood or saliva to look for inherited DNA changes that increase the risk of cancer. Results of genetic testing might help guide your treatment. The results also can show whether family members might have an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

Staging

After confirming a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, your health care team works to find the extent of the cancer. This is called the stage of the cancer. Your health care team uses your cancer's stage to understand your prognosis and create a treatment plan.

The stages of pancreatic cancer use the numbers 0 to 4. In the lowest stages, the cancer is only in the pancreas. As the cancer grows, the stage increases. By stage 4, the cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

More Information

Treatment

Treatment for pancreatic cancer depends on the stage of the cancer and the location. Your health care team also considers your overall health and your preferences. For most people, the first goal of pancreatic cancer treatment is to get rid of the cancer, when possible. When that isn't possible, the focus may be on improving quality of life and keeping the cancer from growing or causing more harm.

Pancreatic cancer treatments may include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy or a combination of these. When the cancer is advanced, these treatments aren't likely to help. So treatment focuses on relieving symptoms to keep you as comfortable as possible for as long as possible.

Surgery

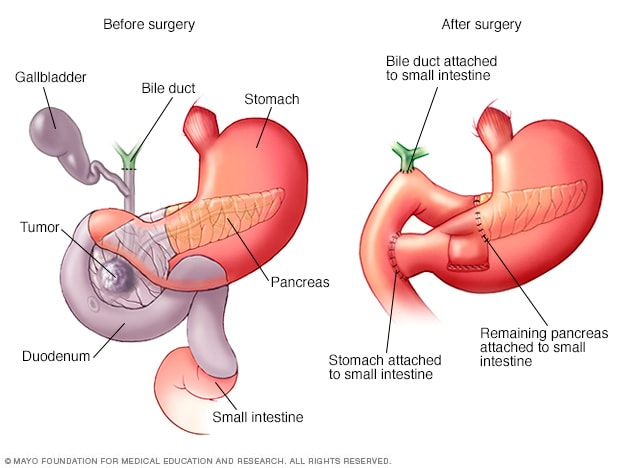

Whipple procedure

Whipple procedure

The Whipple procedure, also called pancreaticoduodenectomy, is an operation to remove the head of the pancreas. The operation also involves removing the first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum, the gallbladder and the bile duct. The remaining organs are rejoined to allow food to move through the digestive system after surgery.

Advanced pancreatic cancer surgeries offer hope.

Click here for an infographic to learn more

Surgery can cure pancreatic cancer, but it's not an option for everyone. It might be used to treat cancer that hasn't spread to other organs. Surgery might not be possible if the cancer grows large or extends into nearby blood vessels. In these situations, treatment might start with other options, such as chemotherapy. Sometimes surgery might be done after these other treatments.

Operations used to treat pancreatic cancer include:

-

Surgery for cancers in the pancreatic head. The Whipple procedure, also called pancreaticoduodenectomy, is an operation to remove the head of the pancreas. It also involves removing the first part of the small intestine and the bile duct. Sometimes the surgeon removes part of the stomach and nearby lymph nodes. The remaining organs are rejoined to allow food to move through the digestive system.

- Surgery for cancers in the body and tail of the pancreas. Surgery to remove the body and tail of the pancreas is called distal pancreatectomy. With this procedure, the surgeon also might need to remove the spleen.

- Surgery to remove the whole pancreas. This is called total pancreatectomy. After surgery, you'll take medicine to replace the hormones and enzymes made by the pancreas for the rest of your life.

- Surgery for cancers that affect nearby blood vessels. When a cancer in the pancreas grows to involve nearby blood vessels, a more-complex procedure might be needed. The procedure might need to involve taking out and rebuilding parts of the blood vessels. Few medical centers in the United States have surgeons trained to do these blood vessel operations safely.

Each of these operations carries the risk of bleeding and infection. After surgery some people have nausea and vomiting if the stomach has trouble emptying, called delayed gastric emptying. Expect a long recovery after any of these procedures. You'll spend several days in the hospital and then recover for several weeks at home.

Research shows that pancreatic cancer surgery tends to cause fewer complications when done by highly experienced surgeons at centers that do many of these operations. Ask about your surgeon's and hospital's experience with pancreatic cancer surgery. If you have any doubts, get a second opinion.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses strong medicines to kill cancer cells. Treatment might involve one chemotherapy medicine or a mix of them. Most chemotherapy medicines are given through a vein, but some are taken in pill form.

Chemotherapy might be the first treatment used when the first treatment can't be surgery. Chemotherapy also might be given at the same time as radiation therapy. Sometimes this combination of treatments shrinks the cancer enough to make surgery possible. This approach to treatment is offered at specialized medical centers that have experience caring for many people with pancreatic cancer.

Chemotherapy is often used after surgery to kill any cancer cells that might remain.

When the cancer is advanced and spreads to other parts of the body, chemotherapy can help control it. Chemotherapy might help relieve symptoms, such as pain.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses powerful energy beams to kill cancer cells. The energy can come from X-rays, protons or other sources. During radiation therapy, you lie on a table while a machine moves around you. The machine directs radiation to precise points on your body.

Radiation can be used either before or after surgery. It's often done after chemotherapy. Radiation also can be combined with chemotherapy.

When surgery isn't an option, radiation therapy and chemotherapy might be the first treatment. This combination of treatments might shrink the cancer and make surgery possible.

When the cancer spreads to other parts of the body, radiation therapy can help relieve symptoms, such as pain.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment with medicine that helps the body's immune system kill cancer cells. The immune system fights off diseases by attacking germs and other cells that shouldn't be in the body. Cancer cells survive by hiding from the immune system. Immunotherapy helps the immune system cells find and kill the cancer cells. Immunotherapy might be an option if your pancreatic cancer has specific DNA changes that would make the cancer likely to respond to these treatments.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are studies of new treatments. These studies provide a chance to try the latest treatments. The risk of side effects might not be known. Ask your health care professional if you might be able to be in a clinical trial.

Palliative care

Palliative care is a special type of health care that helps people with serious illness feel better. If you have cancer, palliative care can help relieve pain and other symptoms. A team of health care professionals does palliative care. The team can include doctors, nurses and other specially trained professionals. The team's goal is to improve quality of life for you and your family.

Palliative care specialists work with you, your family and your care team to help you feel better. They provide an extra layer of support while you have cancer treatment. You can have palliative care at the same time as strong cancer treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

When palliative care is used with all the other appropriate treatments, people with cancer may feel better and live longer.

More Information

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Alternative medicine

Some integrative medicine and alternative therapies may help with symptoms caused by cancer or cancer treatments.

Treatments to help you cope with distress

People with cancer often have distress. Distress might feel like worry, fear, anger and sadness. If have these feelings, you may find it hard to sleep. You might think about your cancer all the time.

Discuss your feelings with a member of your health care team. Specialists can help you sort through your feelings. They can help you find ways to cope. In some cases, medicines may help.

Integrative medicine and alternative therapies also may help you cope with your feelings. Examples include:

- Art therapy.

- Exercise.

- Meditation.

- Music therapy.

- Relaxation exercises.

- Spirituality.

Talk with a member of your health care team if you'd like to try some of these treatment options.

Coping and support

Learning you have a life-threatening illness can feel stressful. Some of the following suggestions may help:

-

Learn about your cancer. Learn enough about your cancer to help you make decisions about your care. Ask a member of your health care team about the details of your cancer and your treatment options. Ask about trusted sources of more information.

If you're doing your own research, good places to start are the National Cancer Institute and the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network.

- Put together a support system. Ask your friends and family to form a support network for you. They might not know what to do after your diagnosis. Helping you with simple tasks might give them comfort and relieve you of those tasks. Think of things you want help with, such as making meals or getting to appointments.

- Find someone to talk with. Although friends and family can often be your best support, sometimes they might find it hard to cope with your diagnosis. It might help to talk with a counselor, medical social worker, or a pastoral or religious counselor. Ask a member of your health care team for a referral.

- Connect with other cancer survivors. You may find comfort in talking with other cancer survivors. Contact your local chapter of the American Cancer Society to find cancer support groups in your area. The Pancreatic Cancer Action Network offers support groups online and in person.

- Consider hospice. Hospice care provides comfort and support to people at the end of life and their loved ones. It allows family and friends, with the aid of nurses, social workers and trained volunteers, to care for and comfort a loved one at home or in a hospice setting. Hospice care also gives emotional, social and spiritual support for people who are ill and those closest to them.

Preparing for your appointment

Start by making an appointment with a doctor or other health care professional if you have symptoms that worry you. You might then be referred to:

- A doctor who diagnoses and treats digestive conditions, called a gastroenterologist.

- A doctor who treats cancer, called an oncologist.

- A doctor who uses radiation to treat cancer, called a radiation oncologist.

- A surgeon who specializes in operations on the pancreas, called a surgical oncologist.

What you can do

When you call to make the appointment, ask about anything you need to do for the appointment, such as restricting your diet. Ask a relative or friend to go with you to help you remember all the information.

Make a list of:

- All your symptoms and when they began.

- Key personal information, including any recent changes or stressors and family history of pancreatic cancer.

- All your medicines, vitamins and supplements, including doses.

Questions to ask your doctor

- Do I have pancreatic cancer?

- What is the stage of my cancer?

- Will I need more tests?

- Can my cancer be cured?

- What are my treatment options?

- Can any treatment help me live longer?

- What are the potential risks of each treatment?

- Is there one treatment you think is best for me?

- What advice would you give a friend or a family member in my situation?

- What is your experience with pancreatic cancer diagnosis and treatment? How many surgical procedures for this type of cancer does this medical center do each year?

- What can be done to help ease my symptoms?

- What clinical trials are available for pancreatic cancer? Am I eligible for any?

- Am I eligible for molecular profiling of my cancer?

- Do you have brochures or other printed material that I can take? What websites do you recommend?

What to expect from your doctor

Be prepared to answer some questions about your symptoms and your health, such as:

- Do you have symptoms all the time, or do they come and go?

- Do your symptoms get in the way of your everyday activities?

- Does anything make your symptoms worse or better?