Overview

Peritoneal dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis

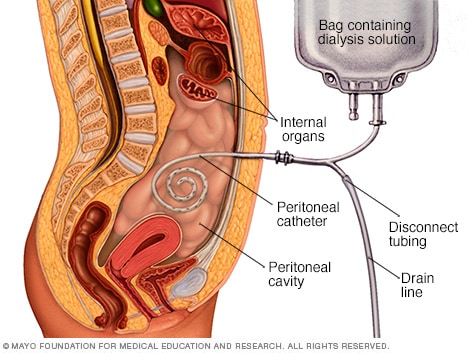

During peritoneal dialysis, a cleansing fluid called dialysate passes through a catheter tube into part of the abdomen known as the peritoneal cavity. The dialysate absorbs waste products from blood vessels in the lining of the abdomen, called the peritoneum. Then the fluid is drawn back out of the body and discarded.

Peritoneal dialysis (per-ih-toe-NEE-ul die-AL-uh-sis) is a way to remove waste products from the blood. It's a treatment for kidney failure, a condition where the kidneys can't filter blood well enough any longer.

During peritoneal dialysis, a cleansing fluid flows through a tube into part of the stomach area, also called the abdomen. The inner lining of the abdomen, known as the peritoneum, acts as a filter and removes wastes from blood. After a set amount of time, the fluid with the filtered waste flows out of the abdomen and is thrown away.

Because peritoneal dialysis works inside the body, it's different from a more-common procedure to clean the blood called hemodialysis. That procedure filters blood outside the body in a machine.

Peritoneal dialysis treatments can be done at home, at work or while you travel. But it's not a treatment option for everyone with kidney failure. You need to be able to use your hands in a skillful way and care for yourself at home. Or you need a trusted caregiver to help you with this process.

Products & Services

Why it's done

You need dialysis if your kidneys no longer work well enough. Kidney damage often becomes worse over many years due to health issues such as:

- Diabetes mellitus.

- High blood pressure.

- A group of diseases called glomerulonephritis, which damage the part of the kidneys that filter blood.

- Genetic diseases, including one called polycystic kidney disease that causes many cysts to form in the kidneys.

- Use of medicines that could damage the kidneys. This includes heavy or long-term use of pain relievers such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve).

In hemodialysis, blood is removed from the body and filtered through a machine. Then the filtered blood is returned to the body. This procedure often is done in a health care setting, such as a dialysis center or hospital. Sometimes, it can be done at home.

Both types of dialysis can filter blood. But the benefits of peritoneal dialysis compared with hemodialysis include:

- More independence and time for your daily routine. Often, you can do peritoneal dialysis at home, work or in any other space that is clean and dry. This can be convenient if you have a job, travel or live far from a hemodialysis center.

- A less restricted diet. Peritoneal dialysis is done in a more continuous way than hemodialysis. Less potassium, sodium and fluid build up in the body as a result. This lets you have a more flexible diet than you could have on hemodialysis.

- Longer-lasting kidney function. With kidney failure, the kidneys lose most of their ability to function. But they still may be able to do a little bit of work for a time. People who use peritoneal dialysis might keep this leftover kidney function slightly longer than people who use hemodialysis.

- No needles in a vein. Before you start peritoneal dialysis, a catheter tube is placed in your belly with surgery. Cleansing dialysis fluid enters and exits your body through this tube once you begin treatment. But with hemodialysis, needles need to be placed in a vein at the start of each treatment so the blood can be cleaned outside the body.

Talk with your care team about which type of dialysis might be best for you. Factors to think about include your:

- Kidney function.

- Overall health.

- Personal preferences.

- Home situation.

- Lifestyle.

Peritoneal dialysis may be the better choice if you:

- Have trouble coping with side effects that may happen during hemodialysis. These include muscle cramps or a sudden drop in blood pressure.

- Want a treatment that's less likely to get in the way of your daily routine.

- Want to work or travel more easily.

- Have some leftover kidney function.

Peritoneal dialysis might not work if you have:

- Scars in your abdomen from past surgeries.

- A large area of weakened muscle in the abdomen, called a hernia.

- Trouble caring for yourself, or a lack of caregiving support.

- Some conditions that affect the digestive tract, such as inflammatory bowel disease or frequent bouts of diverticulitis.

In time, it's also likely that people using peritoneal dialysis will lose enough kidney function to need hemodialysis or a kidney transplant.

Risks

Complications of peritoneal dialysis can include:

-

Infections. An infection of the abdomen's inner lining is called peritonitis. This is a common complication of peritoneal dialysis. An infection also can start at the site where the catheter is placed to carry the cleansing fluid, called dialysate, into and out of the abdomen. The risk of infection is greater if the person doing the dialysis isn't well trained.

To lower the risk of an infection, wash your hands with soap and warm water before you touch your catheter. Each day, clean the area where the tube goes into your body — ask your health care provider which cleanser to use. Keep the catheter dry except during showers. Also, wear a surgical mask over your nose and mouth while you drain and refill the cleansing fluid.

- Weight gain. Dialysate contains sugar called dextrose. If your body absorbs some of this fluid, it might cause you to take in hundreds of extra calories daily, leading to weight gain. The extra calories also can cause high blood sugar, especially if you have diabetes.

- Hernia. Holding fluid in the body for long amounts of time may strain the muscles of the abdomen.

- Treatment becomes less effective. Peritoneal dialysis can stop working after several years. You may need to switch to hemodialysis.

If you have peritoneal dialysis, you'll need to stay away from:

- Certain medicines that can damage the kidneys, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

-

Soaking in a bath or hot tub. Or swimming in a pool without chlorine, a lake, pond or river. These things raise the risk of infection.

It's fine to take a daily shower. It's also okay to swim in a pool with chlorine once the site where your catheter comes out of your skin is completely healed. Dry this area and change into dry clothes right after you swim.

How you prepare

You'll need surgery to get a catheter placed in your stomach area, often near the bellybutton. The catheter is the tube that carries cleansing fluid in and out of your abdomen. The surgery is done using medicine that keeps you from feeling pain, called anesthesia.

After the tube is placed, your health care provider will probably recommend that you wait at least two weeks before you start peritoneal dialysis treatments. This gives the catheter site time to heal.

You'll also receive training on how to use the peritoneal dialysis equipment.

What you can expect

During peritoneal dialysis:

- The cleansing fluid called dialysate flows into the abdomen. It stays there for a certain amount of time, often 4 to 6 hours. This is called the dwell time. Your health care provider decides how long it lasts.

- Dextrose sugar in the dialysate helps filter waste, chemicals and extra fluid in the blood. It filters these from tiny blood vessels in the lining of the abdomen.

- When the dwell time is over, dialysate — along with waste products drawn from your blood — drains into a sterile bag.

The process of filling and then draining your abdomen is called an exchange. Different types of peritoneal dialysis have different schedules of exchange. The two main types are:

- Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD).

- Continuous cycling peritoneal dialysis (CCPD).

Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD)

You fill your abdomen with dialysate, let it remain there for the dwell time, then drain the fluid. Gravity moves the fluid through the catheter and into and out of your abdomen.

With CAPD:

- You may need 3 to 5 exchanges during the day and one with a longer dwell time while you sleep.

- You can do the exchanges at home, work or another clean, dry place.

- You're free to do your regular activities while the cleansing fluid is inside your body.

Continuous cycling peritoneal dialysis (CCPD)

Another name for this is automated peritoneal dialysis (APD). This method uses a machine called an automated cycler. The machine does the exchanges for you at night while you sleep. It fills your abdomen with dialysate and lets it dwell there. Then it drains the fluid into a sterile bag that you empty in the morning.

With CCPD:

- You must stay attached to the machine while it does exchanges for you at night.

- You aren't connected to the machine during the day. But in the morning, you might start one exchange with a dwell time that lasts the entire day. Follow your care team's directions.

- You might have a lower risk of the infection peritonitis. This is because you connect and disconnect to the dialysis equipment less often than you do with CAPD.

Your care team helps you choose the method of exchange that's best for you. It depends on your health, lifestyle and personal choices. Your care team might suggest certain changes to tailor the procedure for you.

Results

Many things affect how well peritoneal dialysis works at removing wastes and extra fluid from the blood. These factors include:

- Your size.

- How quickly the inner lining of your abdomen filters waste.

- How much dialysis solution you use.

- The number of daily exchanges.

- Length of dwell times.

- The concentration of sugar in the dialysis solution.

To find out if your dialysis is removing enough waste from your body, you might need certain tests:

- Peritoneal equilibration test (PET). This compares samples of your blood and your dialysis solution during an exchange. The results show whether waste toxins pass quickly or slowly from your blood into the dialysate. That information helps determine whether your dialysis would work better if the cleansing fluid stayed in your abdomen for a shorter or longer time.

- Clearance test. This checks a blood sample and a sample of used dialysis fluid for levels of a waste product called urea. The test helps find out how much urea is being removed from your blood during dialysis. If your body still produces urine, your care team also may take a urine sample to measure how much urea is in it.

If the test results show that your dialysis routine is not removing enough wastes, your care team might:

- Increase the number of exchanges.

- Increase the amount of dialysate you use for each exchange.

- Use a dialysate with a higher concentration of the sugar dextrose.

You can get better dialysis results and boost your overall health by eating the right foods. These include foods that are high in protein and low in sodium and phosphorus. A health professional called a dietitian can make a meal plan just for you. Your diet will likely be based on your weight, personal preferences and how much kidney function you have left. It's also based on any other health conditions you have, such as diabetes or high blood pressure.

Take your medicines exactly as prescribed. This helps you get the best possible results. While you receive peritoneal dialysis, you may need medicines that help:

- Control blood pressure.

- Help the body make red blood cells.

- Control the levels of certain nutrients in the blood.

- Prevent phosphorus from building up in the blood.