May 25, 2022

Gender disparities have existed for two decades between men and women requiring deceased liver transplant, due to inequities inherent to the Model for End Stage Liver Transplant (MELD) scoring system determining a patient's transplant urgency. Now, national transplant community leadership, including Julie K. Heimbach, M.D., liver transplant surgeon at Mayo Clinic's campus in Minnesota and prior chair of Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing (OPTN/UNOS) Liver and Intestinal Organ Transplantation Committee, seeks to equalize liver transplant opportunity between genders with a proposal for MELD 3.0, published in a 2021 issue of Gastroenterology. MELD 3.0 was adopted on June 27, 2022, and it is pending implementation.

Recognition of MELD's gender bias and movement toward resolution

The MELD-based allocation system used since 2002, with a revised version adopted in 2016, has been effective in reducing waitlist mortality overall by prioritizing the most urgent candidates for transplant. Unfortunately, this system has performed less well for female waitlisted candidates, who have experienced 15% lower transplant rate and significantly higher waitlist mortality compared to males.

Patrick S. Kamath, M.D., gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic's campus in Minnesota, was one of the creators of the MELD scoring system in 2002, originally named the Mayo End-Stage Liver Disease score. The MELD system was not intended to favor men needing liver transplant, and the system's sex-based disparities were not anticipated, says Dr. Heimbach. However, beginning in 2008, multiple studies recognized liver transplant selection disparities between male and female patients. Though Mayo Clinic transplant specialists and others published content about MELD's gender-related disparities, change has been slow, in part because other priorities — such as addressing the complex topic of geographic disparity in access to transplant — took priority, according to Dr. Heimbach.

Dr. Heimbach indicates that remedying MELD's geographic disparities took longer than national transplant leadership anticipated, lasting approximately eight years. When the system finally was revised to address geographic disparity in access to liver transplant with the adoption of a new circle-based organ distribution system in February 2020, an opportunity finally arose to address the long-standing disparity in access to liver transplant experienced by women. Work led by Drs. Kim and Kwong from Stanford with contributions from Drs. Kamath and Heimbach, among several other co-authors, on a revised scoring system version correcting the disparity for women introduced by the original MELD score model had been just completed and published and was ready for consideration, so the timing was finally aligned.

Factors contributing to gender bias in current MELD scoring and MELD 3.0's correction

Multiple factors impact the current MELD scoring gender bias; the crucial one is using creatinine, a muscle metabolism byproduct utilized to estimate kidney function, as one of the values used to calculate the overall priority score. Because women have less muscle than men, they do not produce equivalent creatinine volumes. Creatine differences, therefore, made this lab test less accurate in women, as it is less able to identify poor renal function in women, and this led to women's waitlist underprioritization as the scores did not accurately predict their degree of illness and subsequent risk of death. This factor, along with overprioritization of access for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and the fact that women's size — typically smaller than men — means they cannot be eligible for all of the available livers, led to about 10% to 15% increased death risk for women versus men.

"Creatinine doesn't accurately estimate kidney function in women — it works better in men," says Dr. Heimbach, indicating that laboratory results have verified this issue.

Women needing liver transplant, therefore, bore the implications of MELD's gender bias through living with illness longer, a higher death rate, lower transplant rates and likely longer hospital stays, per Dr. Heimbach. The proposal being considered to equalize access for women improves the c-statistic, a discrimination measurement, for both men and women, so the new proposed system works better for everyone. One optimization in the newly presented model is inclusion of an albumin measurement, improving predictability for men and women, says Dr. Heimbach.

"We made this system with a flaw; now we can correct it," says Dr. Heimbach. "MELD 3.0 is actually an improvement for all patients as the scoring is more accurate, which is ideal, though the bulk of the improvement in predictability is for women."

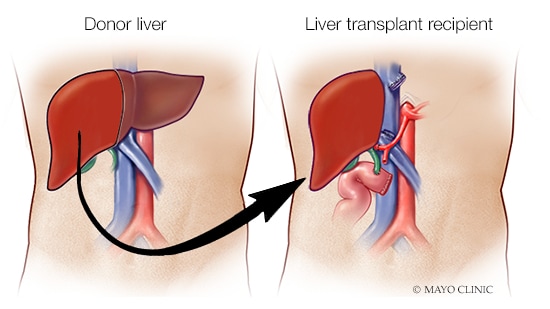

Deceased donor liver transplant

Deceased donor liver transplant

A liver from a deceased donor is transplanted to the recipient.

Dr. Heimbach says MELD 3.0 addresses the root of the current challenge for women who need liver transplantation. She recognizes, however, that many other inequities still exist that impact access to transplantation as well as health care access in general, such as economic disadvantages, lack of health care coverage that disproportionately impacts minority patients, delay in referral for transplantation, and even daily challenges such as transportation, food insecurity and housing that can impact a patient's ability to access transplant services. These ongoing issues will require dedicated attention across multiple parts of the health care system.

"It's really positive and hopefully it will work well," says Dr. Heimbach. "I think it's fantastic for my female patients."

Dr. Heimbach indicates that amending a MELD scoring system disadvantageous to women was an aspiration she held when starting as OPTN/UNOS Liver and Intestinal Organ Transplantation Committee chair.

"During my six years of service on the committee, the two things I wanted most to be able to fix coming in were women's and children's liver transplant inequities created by the allocation system," says Dr. Heimbach. Both of these issues have policy proposals being considered by the OPTN Board this June.

Although Dr. Heimbach feels confident that, if adopted, MELD 3.0 will make a difference for females needing transplant, this policy change does not resolve the underlying shortage of available organs for transplant, and she reminds those seeing patients who are suffering from lack of access to transplantation that living donor liver transplantation is also available and is a life-saving option to consider for those who are suffering from complications of their liver disease but have a MELD score that is too low to access liver transplantation in a timely way. The living donor transplant process is not influenced by MELD scores and can be the best option for many waitlisted patients, depending on their clinical situations.

For more information

Kim WR, et al. MELD 3.0: The model for end-stage liver disease updated for the modern era. Gastroenterology. 2021; 161:1887.

Wu EM, et al. Gender differences in hepatocellular cancer: Disparities in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/steatohepatitis and liver transplantation. Hepatoma Research. 2018;4:66.

Refer a patient to Mayo Clinic.