Jan. 11, 2019

Children with epilepsy are benefiting from Mayo Clinic's recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. Mayo's routine clinical use of a unique imaging protocol is improving detection of focal cortical dysplasia. In addition, Mayo Clinic researchers are working to develop biomarkers for antibody-negative neuroinflammation causing epilepsy and cognitive impairment.

Enhanced diagnosis of focal cortical dysplasia

Morphometric MRI analysis for focal cortical dysplasia

Morphometric MRI analysis for focal cortical dysplasia

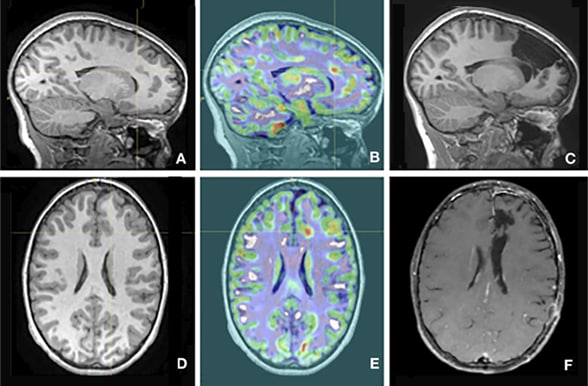

Sagittal and axial images illustrate Mayo Clinic's use of morphometric MRI analysis for focal cortical dysplasia. A and D. Evidence of focal cortical dysplasia doesn't appear in MRIs. B and E. Morphometric MRI analysis indicates focal cortical dysplasia at the crosshair. C and F. Resected areas are visible. Images courtesy of Benjamin Brinkmann, Ph.D.

Mayo Clinic is one of the few centers that routinely offers morphometric MRI analysis to detect focal cortical dysplasia in children. The quantitative analysis, with voxel-by-voxel comparisons between patient MRIs and a normative pediatric sample, can detect the subtle signs of focal cortical dysplasia and guide decisions about surgical treatment.

"Many of these patients start having seizures during the first decade of life. Their families are told that the MRIs are normal, so if a child is failing medications, nothing can be done. Our testing can show that perhaps there is a surgical option," says Lily C. Wong-Kisiel, M.D., a pediatric epileptologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Even with high-tesla MRI, evidence of focal cortical dysplasia is often subtle, as it tends to occur in the gradient between the brain's cortical surface and white matter. Double inversion recovery MRI, which suppresses the white matter signal, can help with detection. "But even then, focal cortical dysplasia can be easily missed," Dr. Wong-Kisiel says.

The use of a normative pediatric database is key to Mayo Clinic's morphometric MRI analysis. "It's unusual to have that normative database in a pediatric population. Assembling it took some time," Dr. Wong-Kisiel says. "But comparing the patient's information to those statistical population norms enhances the radiological detection. As a result, we're picking up additional cases of focal cortical dysplasia."

In a study published in the February 2018 issue of Epilepsy Research, Dr. Wong-Kisiel and colleagues described the enhanced sensitivity of the quantitative MRI analysis compared with visual analysis. The version of the test now in routine clinical use at Mayo was developed by Mayo Clinic's Center for Innovation.

Dr. Wong-Kisiel notes that only 30 to 40 percent of children with MRI-negative epilepsy achieve seizure-free outcomes after surgery, versus 60 to 80 percent of children with a visible MRI finding. "If there's a visual target, we can talk to families about the higher likelihood of successful surgery," she says.

Antibody-negative inflammatory seizures

Mayo Clinic researchers are investigating epileptic encephalopathies in children that appear to be caused by neuroinflammation in the absence of antibodies. Patients with this type of seizure disorder can present with signs and symptoms similar to those seen with autoimmune epilepsy.

"A child who previously was doing well and then has an epileptic encephalopathy of unclear etiology, with an explosive onset and deterioration cognitively, could very well have an inflammatory-mediated disease process even when autoantibodies are not identified, " says Eric T. Payne, M.D., M.P.H., a pediatric epileptologist at Mayo Clinic's campus in Minnesota.

Dr. Payne is working with Charles L. Howe, Ph.D., director of Mayo's Translational Neuroimmunology Laboratory, to find biomarkers for these antibody-negative inflammatory seizures. Blood and cerebral spinal fluid samples from 20 patients have been analyzed.

"We've found that certain inflammatory systems, such as the cytokine interleukin-1 system, are significantly elevated in some of these samples," Dr. Payne says. "It looks as though some of these children are unable to produce functional IL-1 antagonist. That's very interesting because there are IL-1 antagonist therapies, including anakinra, available for use."

In an article published in the December 2016 issue of Annals of Neurology, Dr. Payne and colleagues described the first reported use of anakinra to treat a child with superrefractory status epilepticus secondary to febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES). The patient, who presented at Mayo Clinic at age 32 months, has tolerated treatment with anakinra for more than 12 months. She experiences rare focal seizures but exceeds her pre-illness developmental and cognitive levels.

"Prior to this girl, every patient I had seen with FIRES either died or experienced devastating disabilities, including an inability to walk or talk," Dr. Payne says. "Since our study was published, we get monthly emails from doctors asking us about similar patients they've seen. Some of the patient samples we're analyzing have come from these other centers."

Dr. Payne notes that inflammatory-mediated epilepsy ranges in severity, and the etiology likely involves a number of possible pathways. "FIRES itself might have a heterogeneous etiology," he says. "Although the patient described in our published case report lacked the ability to form functional IL-1 antagonist, we don't know that's the case for everyone with FIRES."

Dr. Payne hopes that further exploration yields information that can be incorporated into standard diagnosis and treatment of status epilepticus. "Why is it that one child might have a seizure that stops after two minutes, another kid's seizures will stop with a bit of medicine and other kids go on to be refractory to medication? Maybe there's an inflammatory process that we haven't yet factored in," he says.

For more information

Wong-Kisiel LC, et al. Morphometric analysis on T1-weighted MRI complements visual MRI review in focal cortical dysplasia. Epilepsy Research. 2018;140:184.

Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation

Kenney-Jung DL, et al. Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome treated with anakinra. Annals of Neurology. 2016;80:939.

Mayo Clinic Translational Neuroimmunology Laboratory