Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return

Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return

Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return

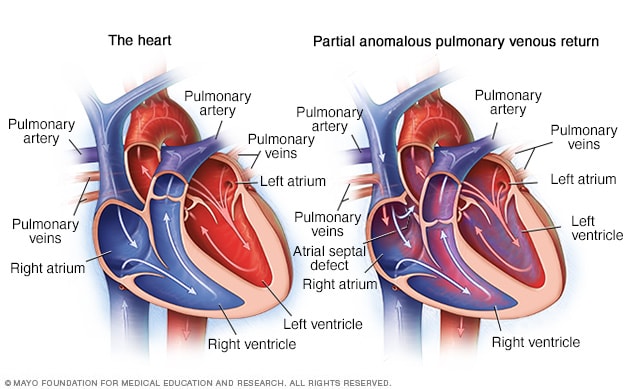

In partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, some of the pulmonary veins incorrectly send blood to the heart's upper right chamber. That chamber is called the right atrium. Usually, oxygen-rich blood flows from the pulmonary veins to the upper left heart chamber, as shown on the left.

Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return is a rare heart condition that's present at birth. That means it is a congenital heart defect.

Other names for this condition are:

- PAPVR (partial anomalous pulmonary venous return).

- PAPVC (partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection).

In this condition, some of the blood vessels of the lungs attach to the wrong place in the heart. These blood vessels are called the pulmonary veins.

In a typical heart, oxygen-rich blood returns from the lungs to the upper left heart chamber, called the left atrium. Then the blood goes to the body.

In PAPVR, blood flows from the lungs into the upper right heart chamber, called the right atrium, and then goes to the lungs, even though that blood already has oxygen. This means the right side of the heart has to handle extra blood flow. This may cause swelling of the right heart chambers.

Most people with PAPVR have a hole between the upper heart chambers called sinus venosus atrial septal defect. The hole lets blood flow between the upper heart chambers. Other heart problems also may occur.

Symptoms

Symptoms of partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR) can include trouble breathing or fatigue. Sometimes, there are no noticeable symptoms.

When to see a doctor

Serious congenital heart defects are often diagnosed before or soon after a child is born. If you think that your baby has symptoms of a heart condition, call your child's healthcare professional.

Call your baby's healthcare professional if the baby has trouble breathing or other symptoms of PAPVR.

Causes

The exact cause of partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR) is not known. Most congenital heart defects happen as the unborn baby's heart is forming before birth. An unborn baby also is called a fetus.

Changes in the genes, some medicines or health conditions, and environmental factors may play a role. Lifestyle choices, such as smoking during pregnancy, also may increase the risk of congenital heart defects in the baby.

Risk factors

What increases the risk of PAPVR is not well known. Possible risk factors for congenital heart defects may include:

- Diabetes. Having type 1 or type 2 diabetes during pregnancy may change how the unborn baby's heart forms. Diabetes that develops during pregnancy is called gestational diabetes. It generally doesn't increase a baby's risk of congenital heart defects.

- Genetics. Changes in some genes have been linked to heart conditions at birth. For example, people with Down syndrome are often born with heart conditions. A child born with Turner syndrome also has an increased risk of PAPVR.

- Rubella, also called German measles. Having rubella during pregnancy can cause changes in an unborn baby's heart. A blood test can be done before pregnancy to see if you're immune to rubella. If you're not, you can get a vaccine.

- Some medicines. Some medicines taken during pregnancy may increase the risk of some congenital heart conditions. These include lithium (Lithobid) for bipolar disorder and isotretinoin (Claravis, Myorisan, others), which is used to treat acne. Talk with a healthcare professional about the medicines you take.

- Smoking. If you smoke, quit. Smoking during pregnancy or being around cigarette smoke increases the risk of some congenital heart conditions.

- Alcohol use. Drinking alcohol during pregnancy may increase the risk of heart conditions in the baby.

Diagnosis

To diagnose partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR), a healthcare professional does a physical exam and listens to the heart and lungs. A whooshing sound, called a heart murmur, may be heard if there is a hole in the heart.

PAPVR may be diagnosed soon after birth. Other times, the condition is not discovered until later in life.

Tests

Tests are needed to diagnose partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR).

An ultrasound of the heart called an echocardiogram can sometimes confirm PAPVR. This test uses sound waves to make pictures of the beating heart. An echocardiogram often shows the pulmonary veins, the size of the heart chambers and any holes in the heart. It also measures the speed of blood flow.

Sometimes, an echocardiogram may not detect PAPVR. Other tests such as a CT scan or MRI may be used.

Treatment

Most patients with partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR) need surgery. Surgery to repair the heart may be needed if:

- A lot of oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood mixes in the heart.

- The right side of the heart is a lot larger than usual.

If you don't have symptoms, surgery may not be needed. If surgery for another heart condition is needed, surgeons may repair PAPVR at the same time.

There are several types of surgery for PAPVR. Together, you and your surgeon will talk about the best options. During repair surgery, the heart surgeon will:

- Reconnect the pulmonary veins to the left upper heart chamber.

- Close any holes in the heart.

A person with partial anomalous pulmonary venous return needs regular health checkups for life to check for complications. It's best to see a doctor who is trained in congenital heart diseases. This type of doctor is called a congenital cardiologist.