June 09, 2023

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common motor disability among children and is typically caused by disturbance or damage to the brain occurring in utero or during infancy. This group of disorders affects muscle control, movement or posture. Although the range of physical impairments associated with this syndrome is quite broad, muscle spasticity is the most common movement difficulty experienced by children with CP.

CP-related spasticity can interfere with function and contribute to contractures and boney deformities. In this Q&A, Joline E. Brandenburg, M.D., answers questions about the management of spasticity in children with CP. Dr. Brandenburg is a pediatric physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist and director of the Cerebral Palsy and Spina Bifida Clinic at Mayo Clinic Children's Center in Rochester, Minnesota.

What are the goals of spasticity treatment?

Spasticity treatment goals can vary. These goals may include improved mobility, decreased pain, decreased muscle spasms, increased range of motion, improved fit of orthoses, improved hygiene, improved positioning and prevention of contractures. A well-planned treatment program may help patients delay or avoid the need for orthopedic surgery. And if orthopedic surgery is necessary, optimizing treatment for spasticity before surgery can help patients during post-surgical recovery. However, not all spasticity requires intervention.

When and how are oral medications used to treat spasticity?

Prior to talking about medications for spasticity, it is important to note that spasticity may not need a medication. However, when a child has spasticity affecting muscles in multiple limbs, we often consider use of one or more oral medications. This includes children with CP who have physical function abilities that are classified as level 4 and level 5 using the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS). These children may use powered mobility equipment, or they require a manual wheelchair for mobility. More commonly prescribed oral medications include baclofen, benzodiazepines (diazepam and clonazepam), gabapentin, clonidine and dantrolene.

As noted, oral medications may not be helpful for everyone or a first choice for intervention. If a child with CP has spasticity that is primarily impacting the calf muscles, an oral medication that acts systemically has the potential for side effects that may be more problematic than the focal muscle tone difficulty.

What's important to understand about the use of injectable botulinum toxins?

OnabotulinumtoxinA and abobotulinumtoxinA have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in children over 2 years of age. Both are approved for treatment of upper and lower limb spasticity. IncobotulinumtoxinA is FDA-approved for upper extremities only in children over 2 years of age. Another serotype, rimabotulinumtoxinB is not FDA-approved in children. In some cases, injectable botulinum toxins may be used in combination with oral medications, surgical interventions or other advanced procedures.

When we administer botulinum toxin in children, we have to think about total body dose, regardless of whether the toxin is being used in muscle (skeletal, bladder), glands or elsewhere. In very small children, this does limit how much we can use and may result in needing to pick and choose which muscles are most important for spasticity reduction at time of injection.

Long-term effects associated with injectable botulinum toxins are not well defined or well studied. This treatment appears most effective when partnered with intensive physical or occupational therapy, serial casting, or constraint casting. Muscle atrophy, possibly related to long-term changes in muscle structure, can occur. Reduced effectiveness after long-term use also has been noted.

What are the indications for treatment with intrathecal baclofen, and what other guidelines for its usage should providers be aware of?

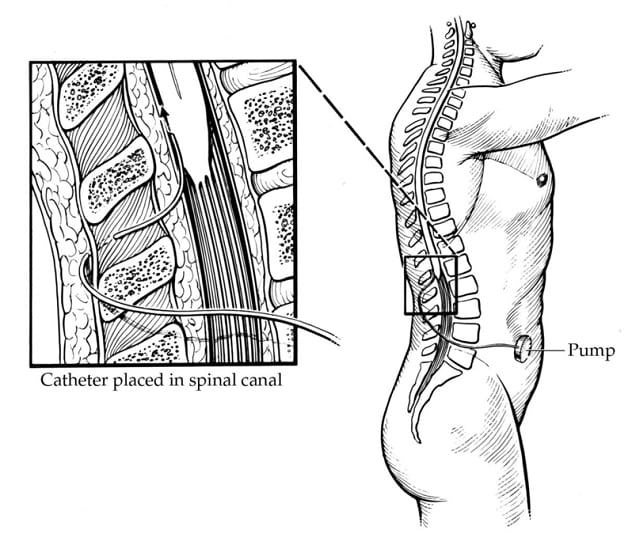

Implanted baclofen pump

Implanted baclofen pump

Intrathecal baclofen (ITB) is an intervention where baclofen is delivered in very small doses directly to the spinal cord. Among children with CP, we typically consider ITB for patients who are nonambulatory (GMFCS levels 4 and 5) and have spasticity interfering with positioning, hygiene, care or comfort, despite trying other interventions.

Intrathecal baclofen (ITB) is an intervention where baclofen is delivered in very small doses directly to the spinal cord. This is done by placing a reservoir for baclofen (baclofen pump) beneath the skin, usually in the abdomen between the bottom of the rib cage and top of the pelvis. A very thin catheter is then tunneled under the skin from the pump to the back and into the spinal fluid of the spinal column.

Among children with CP, we typically consider ITB for patients who are nonambulatory (GMFCS levels 4 and 5) and have spasticity interfering with positioning, hygiene, care or comfort, despite trying other interventions. Patients need to have sufficient body habitus to be able to have the pump implanted (usually a space about the size of a hockey puck). They also need to have social resources and support that allow them to return at regular intervals for baclofen pump refills, as running out of the medication can be life-threatening. Unfortunately, complications can arise with ITB, and these are more frequent in children than in adults who undergo ITB treatment. Some complications occur early after pump placement, but others may not occur until years later. Potential complications include infection, catheter failure (microfractures, fracture, catheter migration, catheter obstruction), and pump failure.

What are the indications for treatment with selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR), and what issues should clinicians consider before prescribing this treatment?

SDR is typically appropriate when the goal is to achieve a permanent reduction in spasticity because spasticity is interfering with function or daily cares. Often this is considered when a patient is having an incomplete response to other spasticity-reducing interventions or having difficulty with side effects from other interventions. The two main approaches for SDR are a limited laminectomy or a multilevel (L1-S2) laminectomy. The procedures work by sectioning and cutting the most overactive portions of sensory nerves.

Ideal candidates for SDR are children ages 3 to 7 years with the following:

- Spastic diplegic CP due to prematurity.

- Ambulation limited by spasticity (GMFCS levels 2 to 3).

- No previous muscle or tendon surgical procedures, or significant joint contractures.

- Sufficient selective lower extremity muscle activation and strength that allows the patient to do a brief single-leg stand or get up from the floor.

However, children with CP who do not fit all these criteria can still be considered for this surgery, but they must be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Contraindications to SDR include presence of other types of movement disorders in addition to spasticity and the inability to comply with extensive rehabilitation needed after this surgical procedure.

It's important to understand that SDR only reduces spasticity. Physical function and walking will not improve unless an intensive therapy program is done after SDR. Clinicians should help the family and patient understand that this procedure is not a cure for CP, and that it will not make a child ambulatory if the child wasn't able to walk before surgery.

In nonambulatory children with CP (GMFCS levels 4 and 5) who have severe spasticity or another movement disorder in addition to spasticity, an SDR combined with a ventral rhizotomy may be an option for reducing muscle stiffness in the legs. The goals of this procedure are to palliate the severe leg stiffness to help with cares, positioning and comfort.

For more information

Brandenburg JE, et al. Spasticity interventions: Decision-making and management. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2023;70:483.

Refer a patient to Mayo Clinic.