March 19, 2021

Twin-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) is a rare yet serious condition, requiring fetal intervention to prevent loss of one or both fetuses. Mayo Clinic is one of a handful of medical centers treating this condition nationwide.

TTTS incidence, staging, risks and detection

TTTS is rare — about 4,500 cases in the U.S. yearly, or about 15% of monochorionic twins — according to the Twin to Twin Transfusion Syndrome Foundation. Vascular communication is present virtually in all monochorionic twins; in most cases, the blood flow is balanced with no net transfusion of blood from one twin to the other.

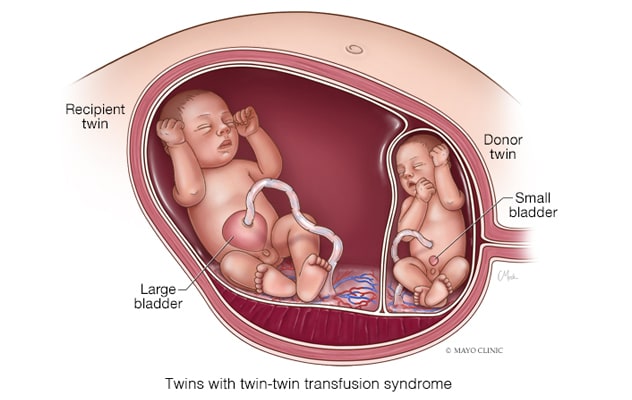

In cases with TTTS, however, the blood flow through these anastomoses is unbalanced, and a net amount of blood is slowly transfused, says Mauro H. Schenone, M.D., chair of Maternal and Fetal Medicine and a maternal fetal medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota. If unaddressed, one fetus becomes hypovolemic and the other becomes hypervolemic. Hypovolemia causes a decrease in the urine output leading to oligohydramnios or anhydramnios, while hypervolemia in the recipient twin causes an increase in the urine output that leads to polyhydramnios. These findings in ultrasound define twin-twin transfusion syndrome.

Based on the severity, TTTS is classified in five stages:

- In stage 1, there is oligohydramnios and polyhydramnios.

- At stage 2, the donor twin's bladder is not visible.

- Progression to stage 3 involves further hemodynamic changes, noticeable with Doppler examination. At this stage, the situation is critical and heart failure may occur, says Dr. Schenone. The fetuses require prompt intervention and the risk of fetal loss without intervention reaches 75% to 100%.

- Stage 4 is characterized by the presence of fetal hydrops.

- The last stage, stage 5, indicates at least one twin has died.

Recommended screening begins at 16 weeks and is performed biweekly. TTTS can develop at any point during pregnancy but typically emerges in the second trimester.

Factors signaling potential TTTS to the obstetrician include:

- Amniotic fluid volume discrepancy in a monochorionic diamniotic gestation

- Rapid abdominal volume expansion and larger than expected uterus for gestational age, accompanied by nausea and vomiting or mirror syndrome, a preeclampsia-like disease observed in some pregnancies with fetal hydrops

Despite reports that in vitro fertilization pregnancies increase identical twinship and thus TTTS rates, Dr. Schenone indicates there aren't specific, proven risk factors for the syndrome. TTTS is unrelated to genetics, and there's little physicians can do for prevention currently.

Laser treatment

Only a few U.S. medical centers treat TTTS. The first documented laser-treated case occurred in 1988. Now that laser treatment is three decades old, methodology and outcomes have improved. "We've gotten much better at laser therapy for TTTS," says Dr. Schenone. "Initially, the aim was for lasering midplacenta without particular attention to what we were lasering."

Twin-twin transfusion syndrome

Twin-twin transfusion syndrome

In twin-twin transfusion syndrome, blood flow through these anastomoses is unbalanced, and a net amount of blood is slowly transfused. If unaddressed, one fetus becomes hypovolemic and the other becomes hypervolemic.

Twin-twin transfusion syndrome treated with FLP

Twin-twin transfusion syndrome treated with FLP

Twin-twin transfusion syndrome can be treated with fetal laser photocoagulation (FLP), which selectively and sequentially ablates connections, depending on the type, to prevent the loss of one or both fetuses.

Currently, fetoscopic laser photocoagulation (FLP) selectively and sequentially ablates connections, depending on the type.

Another aspect of laser treatment's evolution is the Solomon technique or dichorionization, where the surgeon divides the placenta at least functionally in two, working from one placental edge to the other. This method decreases the risk of post-laser twin anemia polycythemia sequence, or imbalanced blood counts between twins.

FLP, though crucial for fetal survival, is not without risk. The mothers may experience discomfort and pain, though generally transient, says Dr. Schenone, who indicates treatment tends to be well tolerated by mothers and riskier for fetuses. The procedure is by nature invasive, though the surgeon uses a minimally invasive technique.

FLP risks include:

- Fetal loss, especially in advanced cases where the fetus is very ill and may not tolerate the procedure

- Premature rupture of membranes

- Chorioamniotic separation

- Premature delivery

- Amniotic fluid leak into the maternal peritoneal cavity

- Infection

- Bleeding

- Accidental injury to tissue or organs near the operative field

FLP is the best treatment option for stages 2 through 4 and is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use during 16 to 26 weeks' gestation.

"There's ongoing research on stage 1, with some favorable results with the use of laser," says Dr. Schenone. "However, we know that a significant proportion of stage 1 cases will revert without intervention. Therefore, a period of expectant management is reasonable and preferred by many," says Dr. Schenone.

When comparing laser therapy with previous TTTS standard care, amnioreduction, Dr. Schenone says draining fluid is in most cases all but a bandage — treating symptoms while not directly addressing the issue of blood transfusion. This treatment is still used outside the FDA-approved gestational age for laser therapy, however, to prolong pregnancy.

FLP is performed by fetal surgeons; however, the approach is multidisciplinary and involves pediatric cardiology, neonatology, nursing and surgical technicians.

"TTTS is a rare occurrence, so you depend on a specialized team consistently participating in FLP procedures and familiar with the equipment, which is seldom used outside TTTS," says Dr. Schenone. "It's imperative for outcomes to have a team familiar with troubleshooting in this procedure and one that can respond quickly."

For more information

How often does TTTS occur? The Twin to Twin Transfusion Syndrome Foundation.

Humanitarian device exemption (HDE). U.S. Food and Drug Administration.