Overview

A donor nephrectomy is a surgical procedure to remove a healthy kidney from a living donor for transplant into a person whose kidneys no longer function properly.

Living-donor kidney transplant is an alternative to deceased-donor kidney transplant. A living donor can donate one of his or her two kidneys, and the remaining kidney is able to perform the necessary functions.

The first successful organ transplant in the U.S. was made possible by a living kidney donor in 1954 and used open surgery for the kidney donation surgery. Currently, the vast majority of kidney donation surgeries are performed using minimally invasive laparoscopic techniques and may include the use of robot-assisted technology.

Living kidney donation via donor nephrectomy is the most common type of living-donor procedure. About 5,000 living kidney donations are performed each year in the U.S.

Products & Services

Why it's done

The kidneys are two bean-shaped organs located on each side of the spine just below the rib cage. Each one is about the size of a fist. The kidneys' main function is to filter and remove excess waste, minerals and fluid from the blood by producing urine.

People with end-stage kidney disease, also called end-stage renal disease, need to have waste removed from their bloodstream through a machine (hemodialysis) or with a procedure to filter the blood (peritoneal dialysis), or by having a kidney transplant.

A kidney transplant is usually the treatment of choice for kidney failure, compared with a lifetime on dialysis.

Living-donor kidney transplants offer several benefits to the recipient, including fewer complications and longer survival of the donor organ when compared with deceased-donor kidney transplants.

The use of donor nephrectomy for living kidney donation has increased in recent years as the number of people waiting for a kidney transplant has grown. The demand for donor kidneys far outnumbers the supply of deceased-donor kidneys, which makes living-donor kidney transplant an attractive option for people in need of a kidney transplant.

Types of live kidney donation

Paired organ donation

Paired organ donation

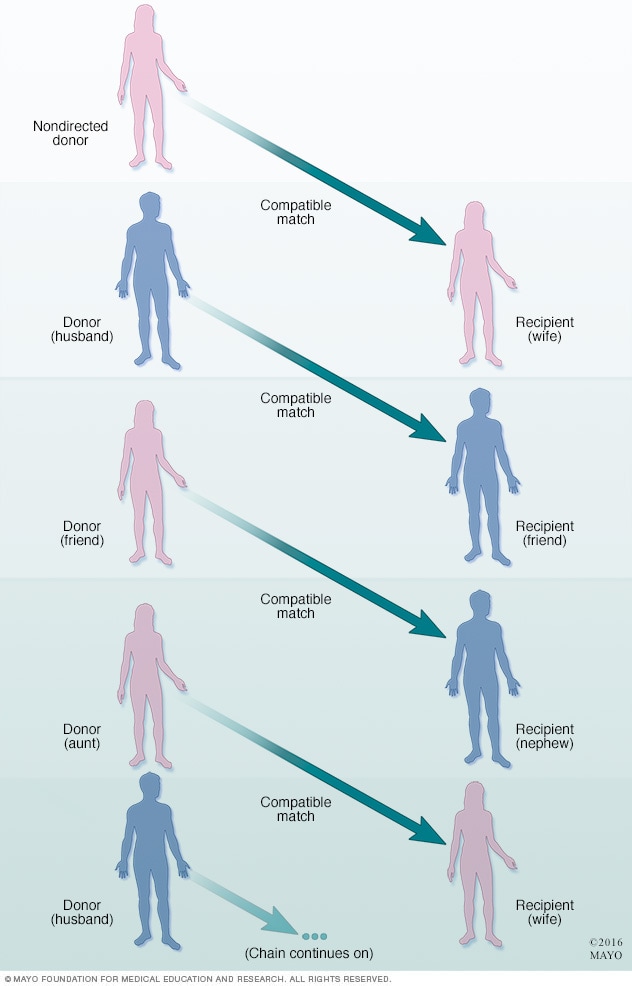

In paired organ donation, living donors and their recipients aren't compatible for a transplant. However, the donor of each pair is compatible with the recipient of the other pair. If both donors and recipients are willing, your healthcare team may consider a paired donation.

Living-donor organ donation chain

Living-donor organ donation chain

More than one pair of living donors and recipients who are not compatible may be linked with a nondirected living donor to form a donation chain in order to receive compatible organs.

You may choose to donate your kidney in one of two ways:

- Directed donation, in which you name a specific transplant recipient. This is the most common type of living-donor organ donation.

- Nondirected donation, also known as good Samaritan or altruistic donation, in which you do not name the recipient of the donated organ. The match is based on medical need and compatibility.

If you and your intended recipient in a directed donation have incompatible blood types or are otherwise not a suitable match, paired-organ donation or donation chain programs may be an option.

- Paired-organ donation. Two or more organ-recipient pairs trade donors so that each recipient gets an organ that is compatible with his or her blood type. A nondirected living donor also may participate in paired-organ donation to help match incompatible pairs.

- Donation chain. More than one pair of incompatible living donors and recipients may be linked with a nondirected living donor to form a donation chain for compatible organs. In this scenario, multiple recipients benefit from a single nondirected living donor.

Risks

Donor nephrectomy carries certain risks associated with the surgery itself, the remaining organ function and the psychological aspects involved with donating an organ.

For the kidney recipient, the risk of transplant surgery is usually low because it is a potentially lifesaving procedure. But kidney donation surgery can expose a healthy person to the risk of and recovery from unnecessary major surgery.

Immediate, surgery-related risks of donor nephrectomy include:

- Pain

- Infection

- Hernia

- Bleeding and blood clots

- Wound complications and, in rare cases, death

Living-donor kidney transplant is the most widely studied type of living organ donation, with more than 50 years of follow-up information. Overall, studies show that life expectancy for those who have donated a kidney is the same as that for similarly matched people who haven't donated.

Some studies suggest living kidney donors may have a slightly higher risk of kidney failure in the future when compared with the average risk of kidney failure in the general population. But the risk of kidney failure after donor nephrectomy is still low.

Specific long-term complications associated with living kidney donation include high blood pressure and elevated protein levels in urine (proteinuria).

Donating a kidney or any other organ may also cause mental health issues, such as symptoms of anxiety and depression. The donated kidney may fail in the recipient and cause feelings of regret, anger or resentment in the donor.

Overall, most living organ donors rate their experiences as positive.

To minimize the potential risks associated with donor nephrectomy, you'll have extensive testing and evaluation to ensure that you're eligible to donate.

How you prepare

Making an informed decision

The decision to donate a kidney is a personal one that deserves careful thought and consideration of both the serious risks and the benefits. Talk through your decision with your friends, family and other trusted advisers.

You should not feel pressured to donate, and you may change your mind at any point.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network require that living-donor transplant centers provide an independent donor advocate to protect the informed consent process. This advocate is often a social worker or counselor who can help you discuss your feelings and answer any questions you have.

General criteria for kidney donation include:

- Age 18 years or older

- General good health

- Two well-functioning kidneys

- A willingness to donate

- No history of high blood pressure, kidney disease, diabetes, certain cancers or major risk factors for heart disease

- Completion of a thorough physical and psychological evaluation at the transplant center

If you meet the requirements to be a living donor, the transplant center is required to inform you of all aspects and potential results of organ donation and obtain your informed consent to the procedure.

Choosing a transplant center

Your physician or your living-donor kidney recipient's physician may recommend a transplant center for your donor nephrectomy.

You're also free to select a transplant center on your own or choose a center from your insurance company's list of preferred providers.

When considering a transplant center, you may want to:

- Learn about the number and type of transplants the center performs each year

- Ask about the transplant center's organ donor and recipient survival rates

- Compare transplant center statistics through the database maintained by the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

- Assess the center's commitment to keeping up with the latest transplant technology and techniques, which indicates that the program is growing

- Consider additional services provided by the transplant center, such as support groups, travel arrangements and referrals to other resources

- Find out if the transplant center participates in paired-organ donation or donation chain programs

What you can expect

Before the procedure

Once you've gone through the living organ donor screening, evaluation and informed consent process, your donor nephrectomy procedure will be scheduled for the same day as the transplant surgery for the recipient. Separate medical teams and surgeons typically perform the donor nephrectomy and the transplant surgery, but they work closely together.

You'll receive instructions about what to do the day before and the day of your kidney donation surgery. Make note of any questions you might have, such as:

- When do I need to begin fasting?

- Can I take my prescription medications?

- If so, how soon before the surgery can I take a dose?

- What nonprescription medications should I avoid?

- When do I need to arrive at the hospital?

During the procedure

Donor nephrectomy

Donor nephrectomy

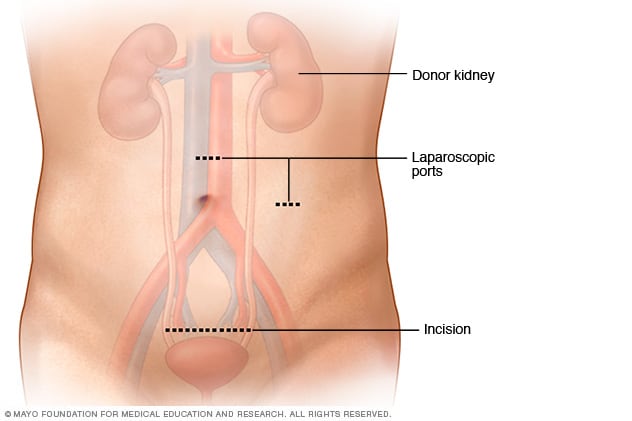

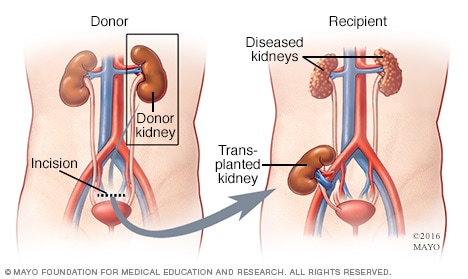

During a living-donor laparoscopic nephrectomy, two or three very small incisions (ports) about 5 to 12 millimeters in size are used to insert the laparoscopic equipment. A slightly larger, 5- to 7-centimeter incision is made above or below the bellybutton for removal of the kidney. The removal incision may be vertical or horizontal depending on your situation.

Living kidney donor laparoscopic nephrectomy

Living kidney donor laparoscopic nephrectomy

In a living-donor laparoscopic nephrectomy, the surgeon uses a special camera called a laparoscope to view the internal organs and guide the procedure to minimize scarring and recovery time. The donor kidney is removed through a small incision below the bellybutton and transplanted into the recipient.

Donor nephrectomy is performed with general anesthesia. This means you will be asleep during the procedure, which usually lasts 2 to 3 hours. The surgical team monitors your heart rate, blood pressure and blood oxygen level throughout the procedure.

Surgeons almost always perform minimally invasive surgery to remove a living donor's kidney (laparoscopic nephrectomy) for a kidney transplant. Laparoscopic nephrectomy is associated with less scarring, less pain and a shorter recovery time than is open surgery to remove a kidney (open nephrectomy).

In a laparoscopic nephrectomy, the surgeon usually makes two or three small incisions in the abdomen. Very small incisions are used as portals (ports) to insert the fiber-optic surgical instruments. A slightly larger incision is used to remove the donor kidney. The equipment includes a small knife, clamps and a special camera called a laparoscope that is used to view the internal organs and guide the surgeon through the procedure.

In open nephrectomy, a 5- to 7-inch (13- to 18-centimeter) incision is made on the side of the chest and upper abdomen. A surgical instrument called a retractor is often used to spread the ribs to access the donor's kidney.

After the procedure

After your donor nephrectomy, you'll likely stay in the hospital for one or two days.

In addition, you can expect:

-

Care after your surgery. If you live far from your transplant center, your health care providers will likely recommend that you stay close to the center for a few days after you leave the hospital so that they can monitor your health and remaining kidney function.

You'll likely need to return to your transplant center for follow-up care, tests and monitoring several times after your surgery. Transplant centers are required to submit follow-up data at six months, 12 months and 24 months after donation. Your primary care provider may conduct your laboratory tests one and two years after your kidney surgery and send the information to the transplant center. Ongoing regular visits at least annually with your health care provider are recommended.

- Recovery. Depending on your overall health, your health care providers will give you specific advice on how to take care of yourself and reduce the risk of complications during your recovery. This can include not sitting or lying in bed for long periods of time, not driving a car for 1 to 2 weeks, not lifting any objects heavier than 10 pounds (4.5 kilograms) for a month, caring for your incision, managing pain, and returning to your regular diet.

- Return to typical activities. After kidney donation, most people are able to return to their regular daily activities after 2 to 4 weeks. You may be advised to avoid contact sports or other strenuous activities that may cause kidney damage.

-

Pregnancy. Kidney donation typically does not affect the ability to become pregnant or complete a safe pregnancy and childbirth. Some studies suggest that kidney donors may have a small increase in risk of pregnancy complications such as gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia and protein in the urine.

It's usually recommended that women wait at least six months to a year after donor nephrectomy before becoming pregnant. Discuss pregnancy plans with your health care provider.

Coping and Support

Becoming a living donor is a deeply personal decision that requires careful consideration of both the serious risks and the benefits. Reaching out to family members, friends, counselors, clergy or people who have gone through this process can be helpful.

Your transplant team also can assist you with useful resources and coping strategies throughout the kidney donation and donor nephrectomy process, such as:

- Joining a support group for organ donors. Talking with others who have shared your experience can ease fears and anxiety.

- Sharing your experiences on social media. Engaging with others who have had a similar experience may help you adjust to your changing situation.

- Educating yourself. Learn as much as you can about your procedure and ask questions about things you don't understand. Knowledge is empowering.

Diet and nutrition

You should be able to go back to your regular diet soon after the kidney donation. Unless you have other health issues, you won't likely have any specific dietary restrictions related to your procedure.

Your transplant team includes a dietitian who can discuss your specific diet needs and questions with you.

Exercise

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle through diet and exercise is just as important for living kidney donors as it is for everyone else.

You can usually return to your typical physical activity levels within a few weeks or months after donor nephrectomy. It's important to talk with your health care provider before starting any new physical activity. Your transplant team can discuss your individual physical activity goals and needs with you.

Some health care providers recommend that living kidney donors protect their remaining kidney by avoiding contact sports, such as football, boxing, hockey, soccer, martial arts or wrestling, and wearing protective gear such as padded vests under clothing to protect the kidney from injury during sports.

Jan. 11, 2024