May 06, 2016

For decades, warfarin was the only available oral anticoagulant and the mainstay for reducing the risk of stroke in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. But warfarin has significant limitations, including slow onset of action, a narrow therapeutic window, dietary and drug restrictions, the need for frequent laboratory monitoring, and an increased risk of bleeding.

To address these issues, pharmaceutical companies began developing novel anticoagulants (NOACs) targeting single enzymes in the coagulation cascade such as thrombin and factor Xa as opposed to the vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors inhibited by warfarin.

Four of these new drugs received Food and Drug Administration approval in the last few years: Apixaban (Eliquis), dabigatran (Pradaxa), edoxaban (Savaysa) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto). They are now used for a growing number of indications — both on- and off-label — including treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism as well as stroke prevention.

"NOACs have no food restrictions, don't require a blood draw and have predictable, dose-dependent anticoagulation effects; patients on dabigatran are fully anticoagulated in two hours and those on rivaroxaban or apixaban in five to 12 hours, so they are far more convenient for patients," explains Erica A. Loomis, M.D., a trauma surgeon at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota.

But NOACs present significant challenges for providers treating patients with major bleeding. For instance, routine laboratory tests aren't sensitive enough for quantitative assessment of an NOAC's effect.

"There is really no way of knowing how anticoagulated a patient is," Dr. Loomis says. "You can try to guess according to when the medication was last taken, but a lot depends on how quickly the liver and kidneys are metabolizing and clearing it."

Reversing NOACs

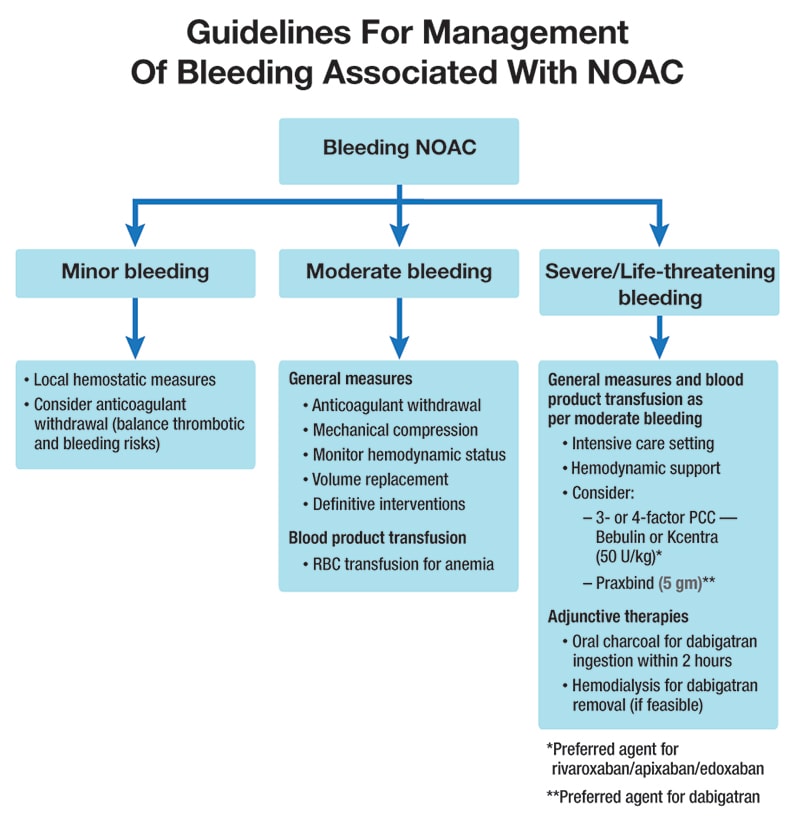

With the exception of dabigatran, no NOAC has a specific antidote. Vitamin K and plasma, standard antidotes for warfarin, aren't effective for NOACs. Plasma can be tried in an emergency situation, Dr. Loomis says, "but there is risk and no clear benefit."

For semiurgent and nonurgent cases, the best option is to hold the drug, which should clear the system in 24 to 72 hours, depending on a patient's liver and kidney function. Activated charcoal is another potential fix — it reduces the absorption of anticoagulants but only if administered within two to three hours of the last drug dose.

Dabigatran has a direct inhibitor, idarucizumab (Praxbind), which is relatively safe, works within about 45 minutes and provides full reversal for up to 24 hours in most patients. It's also expensive — about $3,500 per dose. Praxabind is specific to the reversal of dabigatran and cannot reverse any other agents. In life-threatening situations, dabigatran can also be reversed by dialysis if no other reversal agent is available.

For reversal of other NOACs in cases of life-threatening bleeding, a four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) such as Kcentra is an option. PCCs contain factors II, VII, IX and X and proteins C and S, along with heparin and human albumin. All increase the risk of thrombosis and are usually reserved for the most critical cases.

"Blood levels of novel anticoagulants drop to half within 24 hours, and they are completely cleared within 48 to 72 hours, so in some cases, you won't gain anything by aggressively treating anticoagulation," Dr. Loomis says. "But every patient is a judgment call. I would aggressively reverse NOAC effects in a major brain bleed or any kind of spinal injury, but if it were a spleen or liver injury, I would potentially wait, depending on the patient's clinical status."

On the other hand, she says the majority of critically injured trauma patients do get reversed.

"You treat a patient on a novel anticoagulant just as you would treat one on warfarin," she says. "If you would reverse warfarin, then you should also reverse the NOAC. The bleeding risk is the same and the risk of reversal of the anticoagulant is the same."

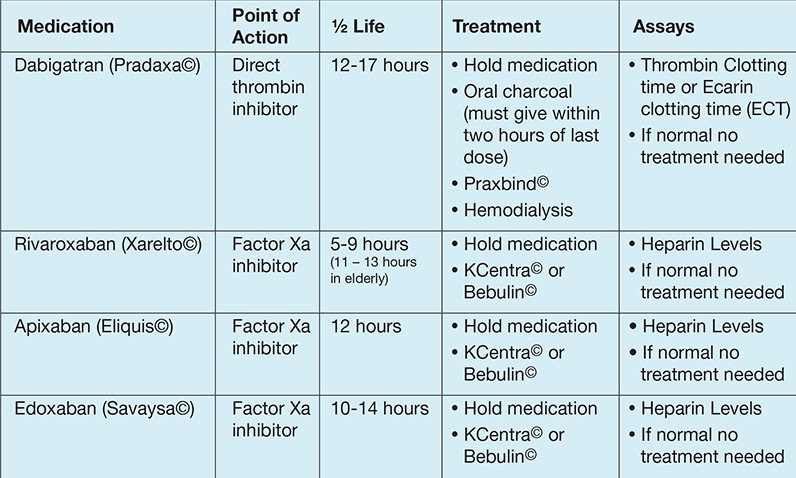

Instructions for NOAC reversal

Instructions for NOAC reversal

NOAC reversal pocket guide

NOAC reversal pocket guide

For centers that don't normally stock idarucizumab or PCCs, the best option is early transfer. Dr. Loomis also recommends that hospital and prehospital providers carry a pocket card with instructions for NOAC reversal.

"There is value to knowing what you need, even if you don't carry it," she explains. "For instance, a flight crew or ground crew could carry the medicine to the facility in need, or it could be administered en route. Everybody can relate to warfarin; this is really no different. The question is, 'How do we go about reversing these agents?' In the case of warfarin, if you don't have plasma, you can give vitamin K. Unfortunately, we don't have that simplicity with NOACs."