Overview

Robotic-assisted surgery setup

Robotic-assisted surgery setup

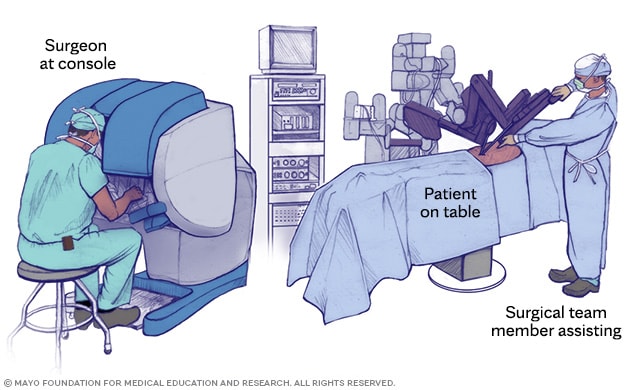

A tiny camera and small robotic tools are inserted through several small cuts in the belly. A surgeon sits at a console and precisely controls the motion of the tools. A team member assists at the operating table.

In a robotic prostatectomy a surgeon uses surgical tools attached to robotic arms to take out all or part of the prostate gland. The prostate gland is part of the male reproductive system. It's located in the pelvis, below the bladder. It surrounds the hollow tube called the urethra that carries urine from the bladder to the outside of the body.

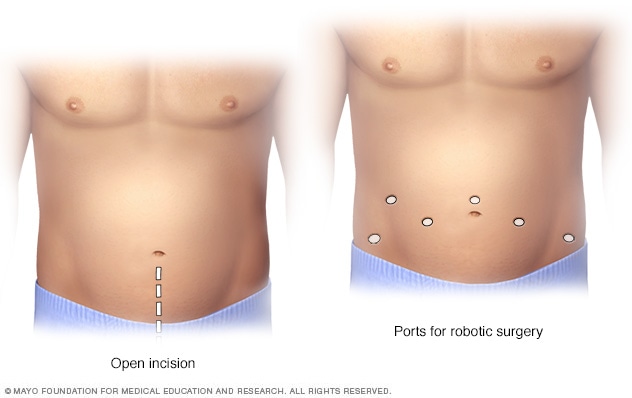

This prostate surgery is different from a traditional open prostatectomy that requires a large, 8- to 10-inch cut. Instead, a robotic prostatectomy uses a minimally invasive approach called laparoscopy. This means it's done through a 1- to 2-inch cut and five much smaller cuts in the lower belly. Less often, it's done through a larger cut in the area between the anus and the scrotum, called the perineum.

Although it's less invasive than open surgery, robotic prostatectomy is considered a major surgery. A robotic prostatectomy is commonly used to treat prostate cancer. It also can treat other prostate conditions.

Types

A robotic prostatectomy may be done using different approaches, depending on the condition that needs treatment.

- Robot-assisted radical laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP). This type of robotic prostatectomy is used to treat prostate cancer. During a radical robotic prostatectomy, a surgeon takes out the entire prostate gland and some surrounding tissues. Sometimes, nearby lymph nodes are taken out too. Another name for this surgery is a robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (RALP).

- Nerve-sparing prostatectomy. A nerve-sparing approach means the surgeon takes out the prostate while trying not to injure the nerves that play a role in erections. This may not be possible if the cancer is very close to the nerves. In that case, a non-nerve-sparing prostatectomy may be needed.

- Simple robotic prostatectomy. Sometimes called a partial prostatectomy, this approach takes out only the inner part of the prostate. It leaves the outer part intact. A simple robotic prostatectomy usually is done to ease symptoms of an enlarged prostate, a condition called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Mayo Clinic urologists use advanced endoscopic techniques to address enlarged prostate symptoms without the need for open, laparoscopic or robotic surgery in most cases.

Your surgical team talks with you about the pros and cons of each technique. You also talk about your preferences. Together, you and your surgical team decide which approach is best for you.

Why it's done

Prostatectomy may be done to treat prostate cancer. It also may be used to treat an enlarged prostate, a condition called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

A robotic prostatectomy lets the surgeon operate with precise movements. It may cause less pain and bleeding than traditional open surgery, and recovery time may be shorter.

Removing prostate due to cancer

Most often, prostatectomy is done to treat cancer that likely hasn't spread beyond the prostate gland. The entire prostate and some tissue around it are taken out. This is called a radical prostatectomy. It may be used alone or with another treatment such as radiation or hormone therapy.

Easing symptoms and complications of BPH

To treat BPH, surgeons take out most of the inner part of the prostate. The outer part is left intact. This is called a simple or partial prostatectomy. It can be a treatment choice for some people with serious urinary symptoms and very enlarged prostate glands.

The surgery eases urinary symptoms and complications resulting from blocked urine flow, such as:

- An urgent need to urinate often.

- Trouble starting urination.

- Slow urination, also called prolonged urination.

- Urinating more than usual at night.

- Stopping and starting again while urinating.

- The feeling of not being able to fully empty the bladder.

- Urinary tract infections.

- Not being able to urinate.

Risks

You may wonder if you can survive or live without a prostate. The answer is yes. A robotic prostatectomy, like any surgery, comes with some risks and side effects. Your healthcare team works to lower these risks.

Radical prostatectomy risks and side effects

Risks and side effects of radical prostatectomy include:

- Bleeding.

- Blood clots.

- The loss of the ability to manage when you urinate, also called urinary incontinence. This often goes away over time.

- Trouble getting and keeping an erection that's firm enough for sex, also called erectile dysfunction.

- Narrowing of the tube through which urine leaves the body, called the urethra. Or narrowing of the neck of the bladder, where the urethra and bladder meet.

- A collection of fluid called lymph.

- Rarely, damage to the intestine or rectum.

Some pain is common for several weeks after surgery. Your healthcare team works with you to create a pain control plan.

Compared with an open prostatectomy, robot-assisted prostatectomy can result in less blood loss and pain, a shorter hospital stay, and a quicker recovery.

At Mayo Clinic, the urologists who do prostatectomies have advanced training and extensive experience in all aspects of the surgery. Much of this expertise stems from the high numbers of people treated. Mayo Clinic's high volumes for surgeries, clinical trials and advanced treatments support an optimal experience for people receiving care. Plus, Mayo Clinic's approach is deeply informed by prostate anatomy, focusing on preserving urinary control and sexual function during treatment. People benefit from a comprehensive and empathetic approach that emphasizes both physical outcomes and quality of life. This ensures the lowest complication rates and optimal outcomes for people who have this surgery.

Simple prostatectomy risks and side effects

Simple prostatectomy, which removes most of the inner prostate tissue, works well at easing urinary symptoms. But it has a higher risk of some complications and a longer recovery time than other, less invasive treatments for an enlarged prostate. One such treatment is a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). During TURP, a surgeon takes out only small pieces of prostate tissue. This is done through the urethra, the tube that carries urine out of the body. Other examples of less invasive treatments include laser photoselective vaporization of the prostate, also called laser PVP surgery, and holmium laser prostate surgery (HoLEP).

Risks and side effects of simple prostatectomy include:

- Bleeding.

- Blood clots.

- Urinary tract infection.

- Urinary incontinence.

- Semen going into the bladder instead of leaving the body through the penis during ejaculation. This is called retrograde ejaculation.

- Erectile dysfunction.

- Narrowing of the urethra or bladder neck after open surgery.

Some pain is common for several weeks after surgery. Your healthcare team works with you to create a pain control plan.

When to get medical help

Some side effects are to be expected, but sometimes they may need medical attention.

Call 911 or your local emergency number if you have:

- New pain, swelling, redness, firmness or numbness in one leg, especially if it's in the lower calf.

- Shortness of breath.

- Chest pain or blackouts.

Call your care team right away if you have:

- A clogged catheter, reduced amount of urine or a catheter that falls out.

- Urine that's thick, red and ketchuplike or has clots of blood the size of a small grape or larger.

- Difficult or painful urination.

- Decreased force of urine or not being able to urinate for more than four hours after the catheter is removed.

Call your care team soon if you have:

- New pain or pain not helped by pain medicine.

- Signs of infection such as a temperature of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius) or higher; increasing pain, tenderness or swelling; or foul-smelling drainage or a change in skin color around an incision. This change may be a shade of red, purple or brown depending on your skin color.

- Big change in how your urine smells.

- Leakage or drainage around the catheter more than several times a day for the first few days after surgery. Also call if urine drainage around the catheter is more than the amount going in the drainage bag.

- Bladder spasms, cramping or bruising in your lower back, just under your ribs on either side of your backbone.

- Incision edges that come apart.

- Upset stomach or vomiting.

How you prepare

Before surgery, your surgeon may do a test called cystoscopy. This test uses a device called a scope to look inside your urethra and bladder. Cystoscopy lets your surgeon check the size of your prostate and examine your urinary system. Your surgeon also may want to do other tests. These include blood tests or tests that measure your prostate and urine flow.

Follow your surgery team's instructions on what to do before your surgery.

Food and medicines

Talk with your surgery care team about:

- Your medicines. Tell your surgery team about any medicines or supplements you take, whether you need prescriptions for them or not. This is extra important if you take blood-thinning medicines such as warfarin (Jantoven) or clopidogrel (Plavix). It's also very important to tell your care team if you take some pain relievers that are sold without a prescription. For example, tell your care team if use take aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve). Your surgeon may ask you to stop taking medicines that raise your risk of bleeding a certain number of days before the surgery.

- Medicine allergies or reactions. Talk with your surgery team about any allergies or reactions you have had to medicines.

- Fasting before surgery. Your surgeon likely will ask that you not eat or drink anything after midnight. On the morning of your surgery, take only the medicines your surgeon tells you to with a small sip of water.

- Bowel prep before surgery. You may be given a kit and instructions to help clear your bowels before surgery.

Clothing and personal items

Plan to avoid wearing these items into surgery:

- Jewelry.

- Eyeglasses.

- Contact lenses.

- Dentures.

Arrangements after surgery

Ask your surgeon how long you'll be in the hospital. Arrange in advance for a ride home. You won't be able to drive yourself right after surgery.

Activity restrictions

You may not be able to work or do strenuous activities for weeks after surgery. Ask your surgeon how much recovery time you may need.

What you can expect

Before the procedure

Most often, prostatectomy is done using medicine to prevent pain and put you in a sleeplike state. This is called general anesthetic. Your surgeon also may give you an antibiotic right before surgery to help prevent infection with germs.

During the procedure

Prostatectomy incisions

Prostatectomy incisions

During an open prostatectomy, one large incision is made in the lower stomach area (left). During a robotic prostatectomy, several smaller incisions are made in the stomach area (right).

How long a robotic prostatectomy takes in the operating room can vary. But usually the surgery takes between two and four hours. This doesn't include the time spent getting prepared for surgery or staying in the recovery area after surgery. Overall, everything might take a half day to a full day.

-

Robotic radical prostatectomy. During a radical procedure, a tiny, tube-shaped camera and small robotic tools usually are inserted through several small cuts in your belly. Less often, they might be inserted through a larger cut in the area between your anus and your scrotum called the perineum.

A surgeon sits at a control panel, also called a console. The console is a short distance from you and the operating table. The surgeon precisely controls the motion of the robotic tools. The tools are designed to have a range of motion similar to those of human hands, wrists and fingers.

The console shows a magnified, 3D view of the surgical area. This lets the surgeon picture the surgery in more detail than in traditional laparoscopic surgery. The robotic system lets the surgeon make smaller and more-precise cuts. This helps some people recover faster than with traditional open surgery. The robotic approach also can reduce some complications.

-

Robotic simple prostatectomy. At the start of the surgery, the surgeon may insert a long, flexible viewing scope called a cystoscope through the tip of the penis. This lets the surgeon see inside the urethra, bladder and prostate area. The surgeon then inserts a tube called a catheter into the tip of the penis. The catheter extends into the bladder to drain urine during the surgery. Then usually several small cuts are made in the lower belly.

Once the surgeon has taken out the part of the prostate causing symptoms, 1 to 2 drain tubes may be inserted. The tubes are placed through punctures in the skin near the surgery site. One tube goes directly into the bladder. The other tube goes into the area where the prostate was taken out. In time, the tubes are taken out.

After the procedure

After surgery, you'll likely:

- Receive pain medicines. This might be through a vein (IV) or as prescription pain pills.

- Walk. You might do this the day of or the day after surgery.

- Go home 1 to 2 days after surgery. When your surgeon thinks it's safe for you to go home, your pelvic drain, if you have one, likely will be taken out. You may need to return to the surgeon in one or two weeks to have staples taken out.

- Return home with a catheter in place. Most people need a urinary catheter for 7 to 14 days after surgery.

Common questions include:

- When and how often will I need to see a healthcare professional to make sure everything is OK? After a prostatectomy, you might be asked to see your healthcare professional after the first couple of weeks and again after 6 to 8 weeks. How often you need to see a health professional after that depends on your health and the reason for your prostatectomy. For example, if your prostate was taken out due to cancer, you might need prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood tests to check for cancer recurrence every few months for the first year. Talk with your health professional about what's best for you.

-

What is the recovery time after a prostatectomy? Each person's recovery is different, but you should mostly be back to your usual routine in about 4 to 6 weeks. There may be some differences for certain activities. Make sure you understand the self-care measures you need to take after surgery. For example, do not wear tight-fitting clothing or elastic waistbands that may irritate your skin as it heals. You usually can return to your typical diet.

You may be asked not to drink alcohol for several days or more after surgery and not until you stop taking any prescription pain medicines. Understand any restrictions you need to follow, such as limits on driving or lifting heavy things.

-

What are typical activity restrictions during recovery? Talk with your care team about what's OK for you. Generally, stairs and light household tasks are OK. Do not lift more than 10 pounds for at least four weeks. Also skip vigorous activities that include bending, pulling, pushing, twisting or stooping for at least four weeks. Do not drive or operate machinery until your catheter is taken out and your care team says it's OK.

For a few months, you may be asked to skip activities that require a straddling position. Examples include motorcycle riding and sitting on a bicycle. Talk with your health professional before you resume sexual activity.

Walking is the best form of exercise during recovery. Start slowly, such as walking for a few minutes several times a day. Gradually increase as you feel ready.

- Is it usual to have a swollen testicle after prostatectomy? The testicles don't swell. But after surgery, your upper thigh and your scrotum, which surrounds your testicles, may be swollen and bruised. Usually the swelling goes away within a few days. The bruising usually fades in a few weeks.

- What happens or changes in the body after the prostate is taken out? Prostate surgery can weaken the muscles that control urination. This can cause you to leak urine. You may need to use protective pads or disposable diapers. Your care team may give you exercises to help strengthen bladder muscles after the catheter is taken out. With healing, your ability to manage when you urinate can improve. Most people who have prostate surgery can completely recover their bladder function within one year of surgery. Surgery to take out the prostate also can affect the ability to have an erection.

- Does removal of the prostate gland cause impotence? Prostatectomy can affect the nerves responsible for sexual function. After prostatectomy, the time varies in regaining the ability to have an erection. Some people may have the ability right away. Others may gradually regain the ability with the use of medicine. It can take two years or more for the nerves involved to heal. Most people have at least some loss of the ability to have an erection. The younger you are, the less serious the effects are likely to be. Some older people may not regain sexual function after surgery.

- How do I manage erectile dysfunction after surgery? Talk with your care team before you resume sexual activity. If you have a nerve-sparing surgery, your team may prescribe medical therapy to treat erectile dysfunction. This may include taking medicine, such as tadalafil (Adcirca, Cialis, others) or sildenafil (Revatio, Viagra), twice a week. The medicine helps increase blood flow and oxygen levels in the genital area. This promotes muscle and nerve healing. Take the medicine as prescribed, even if you do not try to have sexual intercourse. After 6 to 12 weeks of this, you can usually take one tablet of this medicine as needed before sexual activity.

- Where does semen or sperm go after a prostatectomy? The prostate gland and the seminal vesicles are removed during prostatectomy. These glands make most of the seminal fluid released during ejaculation. As a result, it is typical to emit little or no fluid at orgasm after prostate surgery.

Results

Radical prostatectomy

Prostate cancer can return after prostatectomy. This is called a recurrence. About 1 in 3 people who have a radical prostatectomy experiences a recurrence within 10 years. This is why you'll need regular PSA blood tests. PSA tests help your healthcare professional watch for a recurrence.

If your prostate has been taken out to treat cancer, your PSA level should be undetectable after surgery.

Simple prostatectomy

A simple prostatectomy usually provides long-term relief of urinary symptoms due to an enlarged prostate. It's the most invasive procedure to treat an enlarged prostate, but serious complications are rare. Most people who have the surgery don't need any follow-up treatment for BPH.

Sept. 19, 2025