Overview

Kidney transplant

Kidney transplant

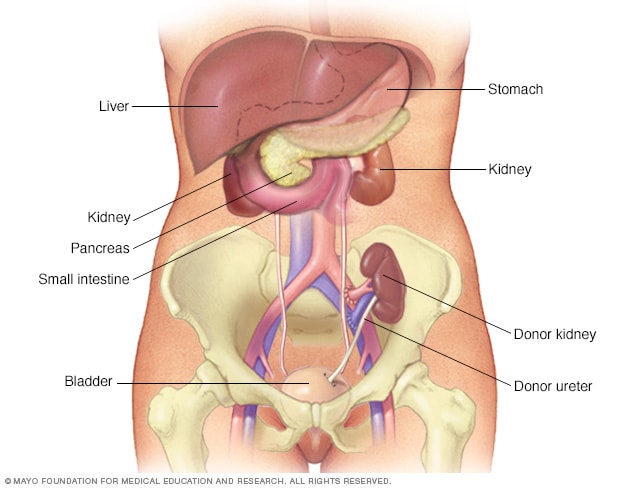

During kidney transplant surgery, the donor kidney is placed in the lower abdomen. Blood vessels of the new kidney are attached to blood vessels in the lower part of your abdomen, just above one of your legs. The new kidney's urine tube (ureter) is connected to your bladder. Unless they are causing complications, your own kidneys are left in place.

In a deceased-donor kidney transplant, a kidney from someone who has just died is given to someone who needs a kidney. The kidney is removed from the person who just died with the consent of the family or based on a donor card. The person who receives the kidney has kidneys that have failed and no longer work properly.

The donated kidney is either stored on ice or hooked up to a machine. The machine provides oxygen and nutrients until the kidney is transplanted into the person who needs it. The donor and recipient are often in the same geographic region. This helps the transplant center reduce the time the kidney is outside a human body.

Only one kidney is needed to meet the body's needs. For this reason, a living person can donate a kidney and still live a healthy life. Living-donor kidney transplant is an alternative to receiving a kidney from someone who has died.

Overall, more than two-thirds of the kidney transplants performed each year in the U.S. are deceased-donor kidney transplants. The rest are living-donor kidney transplants.

The need for deceased-donor kidneys is much larger than the supply. The waiting list for a kidney transplant reached more than 139,000 in 2021.

Products & Services

Why it's done

People with end-stage kidney disease have kidneys that no longer work. People with end-stage kidney disease need to have waste removed from their bloodstream to stay alive. Waste can be removed through a machine in a process called dialysis. Or a person can receive a kidney transplant.

For most people with advanced kidney disease or kidney failure, a kidney transplant is the preferred treatment. Compared to a lifetime on dialysis, a kidney transplant offers a lower risk of death, better quality of life and more dietary options than dialysis.

Risks

The risks of deceased-donor kidney transplant are like the risks of living-donor kidney transplant. Some are like the risks of any surgery. Others have to do with organ rejection and side effects of drugs that prevent rejection. Risks include:

- Pain.

- Infection at incision site.

- Bleeding.

- Blood clots.

- Organ rejection. This is marked by fever, feeling tired, low urine output, and pain and tenderness in the area of the new kidney.

- Side effects of anti-rejection drugs. These include hair growth, acne, weight gain, cancer and increased risk of infections.

How you prepare

If your doctor recommends a kidney transplant, you'll be referred to a transplant center. You can choose a transplant center on your own or choose a center from your insurance company's list of preferred providers.

After you choose a transplant center, you'll be evaluated to see if you meet the center's eligibility criteria. The evaluation may take several days and includes:

- A complete physical exam.

- Imaging tests, such as X-ray, MRI or CT scans.

- Blood tests.

- Cancer screening.

- Psychological evaluation.

- Evaluation of social and financial support.

- Any other tests based on your health history.

After the testing is done, the transplant team will tell you if you're a candidate for transplant. If a compatible living donor isn't available, your name will be placed on a waiting list to receive a kidney from a deceased donor.

Everyone waiting for a deceased-donor organ is registered on a national waiting list. The waiting list is a computer system that stores information on people waiting for a kidney. When a deceased-donor kidney becomes available, information about that kidney is entered into the computer system to look for a match. The computer generates a potential match based on several factors. These include blood type, tissue type, how long the person has been on the waiting list, and distance between the donor hospital and transplant hospital.

The federal government monitors the system to make sure that everyone waiting for an organ has a similar chance. The agency that monitors the system is called the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN).

Some people waiting for a deceased donor get a match within a few months. Others may wait several years. While on the list, you will have a checkup every so often to make sure that you are still a good candidate for a transplant.

What you can expect

The transplant center may identify a deceased-donor kidney that is a good match for you at any time day or night. You will be contacted immediately and asked to come to the transplant center within a certain window of time. You must be ready to go to the center right away to be evaluated.

The transplant team will make sure the kidney is in good shape for transplant. They also will make sure you are still in overall good health and that the kidney is a good match for you. If everything looks good, you'll be prepped for surgery.

During surgery, the donor kidney is placed in your lower abdomen. Blood vessels of the new kidney are attached to blood vessels in the lower part of your abdomen, just above one of your legs. The surgeon also connects the tube from the new kidney to your bladder to allow urine flow. This tube is called the ureter. The surgeon usually leaves your own kidneys in place.

You'll spend several days to a week in the hospital. Your healthcare team will explain what medicines you need to take. They also will tell you what problems to look out for.

Results

After a successful kidney transplant, your new kidney will filter your blood and remove waste. You will no longer need dialysis.

You will take medicines to prevent your body from rejecting your donor kidney. These anti-rejection medicines suppress your immune system. That makes your body more likely to get an infection. As a result, your doctor may prescribe antibacterial, antiviral and antifungal medicines.

It is important to take all your medicines as your doctor prescribes. Your body may reject your new kidney if you skip your medicines even for a short period of time. Contact your transplant team immediately if you have side effects that keep you from taking the medicines.

After the transplant, be sure to perform skin self-checks and get checkups with a dermatologist to screen for skin cancer. Also, staying up to date with other cancer screenings is strongly advised.

The Mayo Clinic experience and patient stories

Our patients tell us that the quality of their interactions, our attention to detail and the efficiency of their visits mean health care like they've never experienced. See the stories of satisfied Mayo Clinic patients.

(VIDEO) Eliminating the need for lifelong immunosuppressive medications for transplant patients

Cindy Kendall donated a kidney and stems cells to her brother, Mark Welter ROCHESTER, Minn. — While immunosuppressive medications are critical to prevent rejection of transplant organs, they also come with plenty of downsides. They can cause harsh side effects, like headaches and tremors, and increase the risk for infection and cancer. But what if there was a way to prevent organ rejection without using these medications? That goal fuels the work of Mark Stegall, M.D.,…

Social worker helps patients on transplant 'journey of cautious hope'

When Tiffany Coco steps into a room at Mayo Clinic Transplant Center in Arizona, she focuses on the patient's needs beyond the medical updates. "Often, patients put their best face forward with the physicians," says Coco, "And when they talk to us, they let their guard down and open up about how transplant affects their day-to-day life." As a licensed clinical social worker embedded in multidisciplinary care teams, Coco uses her clinical expertise to assess…