Sept. 15, 2018

A 37-year-old woman was referred for evaluation of a right adnexal mass in the setting of severely elevated blood pressure and hypokalemia. She was previously healthy and had regular menses since age 11. She had four healthy pregnancies without any complications and had completed childbearing. Four months prior to presentation, her blood pressure during a routine physical exam was 96/54 mm Hg, which was consistent with past blood pressure readings.

CT images showing pelvic mass

CT images showing pelvic mass

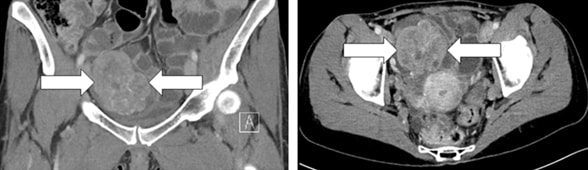

Coronal (left panel) and axial (right panel) CT images showing a 7.5-by-7.5-by-6.5-cm mass (arrows) in the pelvis.

One month prior to the initial evaluation, the patient developed menometrorrhagia and sought care from her local gynecologist. At the initial assessment, her blood pressure was 232/105 mm Hg. A physical exam revealed a solid right adnexal mass. Endometrial biopsy showed no evidence of hyperplasia or carcinoma. Subsequent assessment by a local nephrologist included a normal renal artery ultrasound. Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a large complex solid and cystic right adnexal mass (7.5 by 7.5 by 6.5 cm), located anterior to the uterus and superior to the urinary bladder. There was no abdominal or pelvic lymphadenopathy, and the adrenal glands appeared normal bilaterally.

Laboratory evaluation results

Laboratory evaluation results

Abbreviations used: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; HCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; LH, luteinizing hormone.

Laboratory evaluation showed potassium of 2.7 mmol/L (reference range, 3.6 to 5.2 mmol/L), serum aldosterone of 47 ng/dL (reference range, less than 28 ng/dL), plasma renin activity of 76 ng/mL/hr (reference range, 0.25 to 5.82 ng/mL/hr) and estradiol of 379 pg/mL (reference range, 15 to 350 pg/mL). The patient was started on clonidine 0.1 mg twice daily, metoprolol 50 mg twice daily, spironolactone 50 mg twice daily and potassium chloride 20 mEq three times a day. Despite multiple antihypertensive medications, her blood pressure remained uncontrolled. The patient was then referred to Mayo Clinic for further evaluation and management of the right adnexal mass, secondary aldosteronism and menometrorrhagia. CT angiography was obtained and ruled out stenosis of the intrarenal arteries.

During the initial visit at our institution, her blood pressure was 193/133 mm Hg. Lisinopril 5 mg daily was added to the regimen. The following day, after the second dose of lisinopril, the patient's blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and she was experiencing lightheadedness. A renin- and estradiol-producing ovarian tumor was suspected.

Gross pathology cut section of ovarian steroid cell tumor

Gross pathology cut section of ovarian steroid cell tumor

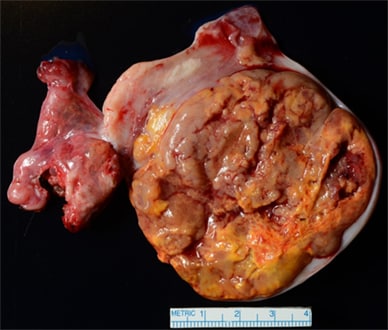

Gross pathology cut section of the 9-by-7.2-by-5-cm ovarian steroid cell tumor.

Microscopic appearance of steroid cell tumor

Microscopic appearance of steroid cell tumor

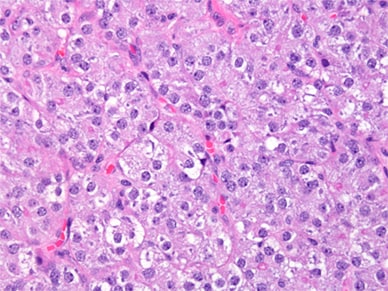

Microscopic appearance of steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified. Cells appear to be round or polyhedral with abundant pale cytoplasm and exhibit a prominent eccentrically located nucleolus. The cells are organized into nests or trabeculae. There are no Reinke crystals, which excludes Leydig cell tumor. Stain: hematoxylin and eosin; 400 times original magnification.

The patient underwent laparoscopic right oophorectomy. A 2-cm vertical infraumbilical skin incision was made to avoid morcellation of this hormonally active tumor. The peritoneal surfaces, omentum, liver and bowel peritoneum were all normal. The uterus and cul-de-sac peritoneum appeared normal, as did the left fallopian tube and ovary. The right ovary contained a 9-by-7.2-by-5-cm mass that was completely covered with normal ovarian surface. There was a sizable portion of the ovary at the periphery of this mass that appeared normal. The right fallopian tube appeared normal, indicating no spread of the tumor beyond the ovary. The specimen was resected and placed in a large bag and removed through the infraumbilical incision. There were no intraoperative complications. Histopathological evaluation demonstrated a steroid cell tumor of the ovary, not otherwise specified (NOS), with no cytologic atypia.

One day after surgery, her blood pressure was 138/95 mm Hg with clonidine monotherapy. Laboratory studies showed normalization of serum potassium (4.4 mmol/L), serum aldosterone (8.4 ng/dL) and plasma renin activity (2.9 ng/mL/hr), and the estradiol level was undetectable. The patient will return for follow-up imaging and laboratory studies in three months.

Discussion

As highlighted in articles in the American Journal of Surgical Pathology and the Journal of Ovarian Research, steroid cell tumors are exceedingly rare sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary. Sex cord-stromal tumors comprise three steroid cell tumor subtypes (steroid cell tumors, NOS; stromal luteomas; and Leydig cell tumors) and account for 5 percent of ovarian tumors and 2 percent of malignant ovarian tumors. As opposed to Leydig cell tumors, steroid cell tumors, NOS, lack crystals of Reinke in the cytoplasm.

Steroid cell tumors typically affect adults with a mean age at diagnosis of 47 years, although cases in young girls (2 to 13 years old) have been described. Approximately 75 percent of steroid cell tumors produce steroid hormones. The most common symptoms include hirsutism and virilization occurring in 56 to 77 percent of patients. Estrogen secretion is reported in 6 to 23 percent of patients. Steroid cell tumors have also been associated with Cushing syndrome in 6 to 10 percent of patients. An elevated renin level, which can produce hypertension and hypokalemia, also has been reported. Although ovarian steroid cell tumors are usually benign, approximately 25 to 43 percent of steroid cell tumors are malignant.

The diagnosis of steroid cell tumors may be challenging. In addition to careful history, physical examination and biochemical testing, CT imaging may identify an adrenal or ovarian mass. Likewise, transabdominal and vaginal ultrasound can be useful in evaluating ovarian size and morphology. If no obvious mass is found on imaging studies, as highlighted in a recent article in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, venous sampling of the adrenal and ovarian veins may localize small steroid-producing tumors.

Similar to other ovarian stromal tumors, surgery is the main treatment for ovarian steroid cell tumors with a goal to achieve a complete resection. Conservative surgery with unilateral oophorectomy and proper staging generally should be performed in women with stage I disease who desire future fertility. For women who have completed childbearing, total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and complete surgical staging is indicated.

Hormonal levels should be monitored as part of the patients' postoperative follow-up. Adjuvant chemotherapy should be based on the histologic appearance of the tumor and on its surgical staging.

For more information

Hayes MC, et al. Ovarian steroid cell tumors (not otherwise specified): A clinicopathological analysis of 63 cases. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1987;11:835.

Jiang W, et al. Benign and malignant ovarian steroid cell tumors, not otherwise specified: Case studies, comparison, and review of the literature. Journal of Ovarian Research. 2013;6:53.

Chen S, et al. Combined ovarian and adrenal venous sampling in the localization of adrenocorticotropic hormone-independent ectopic Cushing syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2018;103:803.