Jan. 07, 2026

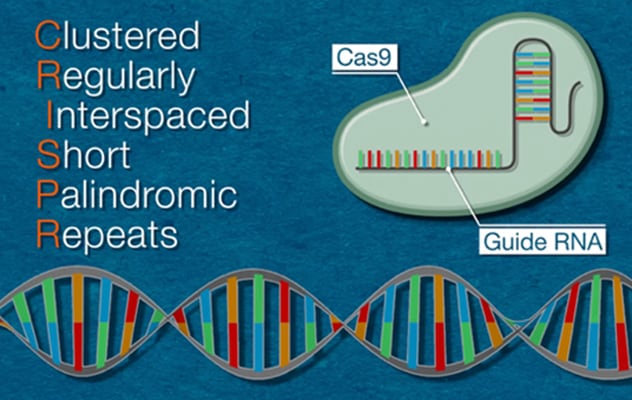

Since it was first used in vertebrates a decade ago, CRISPR/Cas9 has emerged as a powerful tool for gene manipulation in the liver. CRISPR is an abbreviation for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Often portrayed as a cut-and-paste tool for DNA editing, CRISPR consists of two components — a guide RNA (gRNA) that can recognize the sequence of DNA to be edited and the Cas9 protein that can cut DNA.

In a review article published in Hepatology in 2025, Kirk J. Wangensteen, M.D., Ph.D., and co-authors share an in-depth update about how researchers are using CRISPR/Cas9 to study human liver diseases, and the development of this tool as a potential therapy for liver diseases. Dr. Wangensteen is a gastroenterologist and scientist who directs the gastrointestinal neoplasia clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

This Q&A focuses on how CRISPR is used to perform in vivo screening, how integrating CRISPR with single-cell analysis is advancing the study of liver disease, and the development of this tool as a therapy for liver disease.

CRISPR Explained

CRISPR Explained

To use CRISPR/Cas9, scientists first identify the sequence of the human genome that's causing a problem. Then they create a specific gRNA to recognize that particular DNA segment and attach it to the Cas9 protein. After this complex is introduced to target cells, it locates the targeted DNA segment and cuts it. Scientists can then edit the existing genome by either modifying, deleting or inserting new sequences.

How is in vivo screening conducted to study liver disease?

Genetic screening typically involves a multistep process using mouse livers expressing the dead version of Cas9 (dCas9). The researchers deliver a CRISPR plasmid library (usually CRISPR activation or CRISPR interference) to hepatocytes via hydrodynamic tail vein injection (HTVI). This delivery facilitates the selection of hepatocytes with the plasmid integrated into their genomes. Usually, the selection is growth in the setting of an oncogene or repopulation of a Fah−/− mouse.

Overall, how are research advances using this approach impacting the understanding of gene function in the liver?

Although some limitations must still be addressed, published research findings using CRISPR screening performed in vivo in the liver have yielded important discoveries that might not have been possible using cell culture models.

How can in vivo screening be used to explore gene function in tumorigenesis?

Multiple studies have used CRISPR screening to identify gRNAs targeting several tumor suppressor genes, demonstrating the enrichment of gRNAs that can drive tumor growth. Although the findings from this body of research are significant, these studies have some limitations. The insufficient number of tumor clones available to examine has hindered researchers' ability to detect and identify the depletion of gRNAs targeting genes that are required for tumorigenesis. But researchers have made some progress in addressing this challenge, demonstrating that in vivo dropout CRISPR screening is possible with enough selection events and with appropriate library size.

How are in vivo screening approaches helping researchers identify genes associated with liver regeneration?

The Fah−/− liver repopulation model has provided high-quality CRISPR screens. In a study published in Cell Stem Cell in 2022, researchers using CRISPR KO and CRISPRa screens to target chromatin regulatory genes in Fah−/− mice generated consistent results, demonstrating that chromatin remodeling components known as Baz2a and Baz2b negatively regulate liver regeneration. Based on these promising results, researchers are hopeful that targeting these genes could stimulate regenerative responses in the liver and lead to improved liver recovery in humans with acute liver injury.

How is single-cell CRISPR analysis emerging as a tool to study human liver disease?

The integration of CRISPR-based genome-editing techniques with single-cell analysis is evolving as a new approach to studying human liver diseases at a molecular level, offering valuable insights into cellular heterogeneity and disease pathogenesis. In a study published in Science in 2021, lineage tracing revealed that most of liver repopulation occurs in zone 2 of the liver during homeostasis and injuries. Using CRISPR KO and CRISPRa screens in vivo to examine mechanisms driving that zone 2 proliferation, the researchers identified three promoters of proliferation and two negative regulators of proliferation.

How can CRISPR be employed as a treatment for liver disease in humans, and which recent advances are most likely to guide clinical practice now or in the near future?

CRISPR is being investigated as a therapy for multiple liver diseases, including liver cancer and viral hepatitis, and as gene therapy for genetic liver diseases. In a 2025 article published in New England Journal of Medicine, researchers used lipid nanoparticles to deliver CRISPR/Cas9 to a baby with a urea cycle defect.

The liver is becoming a "pioneer organ" for a new generation of medicines that aim to fine-tune or repair genes. We are already seeing early-phase clinical trials underway for CRISPR-based therapies targeting liver diseases such as transthyretin amyloidosis, familial hypercholesterolemia and various monogenic liver disorders. Success in the liver will likely pave the way for similar approaches in other organs, but the liver's unique accessibility and regenerative properties make it the ideal starting point.

Innovations in delivery methods, safety protocols and regulatory pathways for CRISPR-based gene-editing medicines are setting the stage for broad applications in the liver and other tissues. We can anticipate that these treatments will gradually be integrated into our clinical practice for both rare and common diseases.

For more information

Adlat S, et al. Emerging and potential use of CRISPR in human liver disease. Hepatology. 2025;82:232.

Jia Y, et al. In vivo CRISPR screening identifies BAZ2 chromatin remodelers as druggable regulators of mammalian liver regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29:372.

Wei Y, et al. Liver homeostasis is maintained by midlobular zone 2 hepatocytes. Science. 2021;371:906.

Musunuru K, et al. Patient-specific in vivo gene editing to treat a rare genetic disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2025;392:2235.

Refer a patient to Mayo Clinic.