Overview

The liver

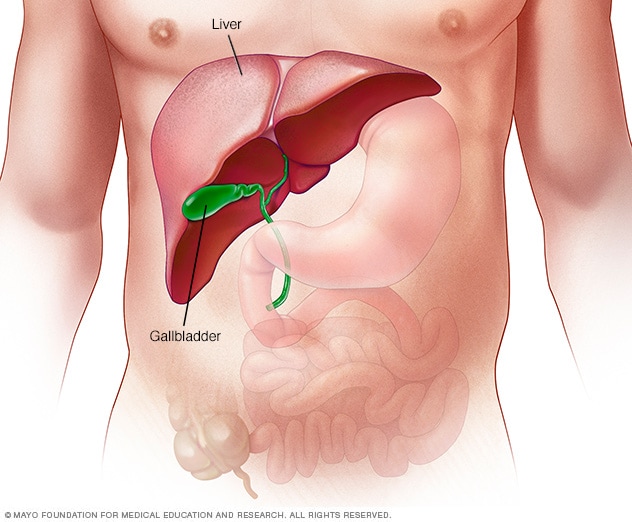

The liver

The largest organ inside the body, the liver is located mainly in the upper right portion of the abdomen, beneath the diaphragm and above the stomach.

Alcoholic hepatitis is a type of liver damage and swelling caused by drinking alcohol. This swelling, called inflammation, damages liver cells. Alcoholic hepatitis most often occurs in people who have been drinking heavily for many years. It also can affect people who binge drink.

Experts increasingly refer to this condition as alcohol-associated hepatitis, a term meant to reduce stigma and emphasize the medical nature of the disease.

Alcoholic hepatitis is a serious form of alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD). ALD includes several types of liver conditions caused by alcohol, from fat deposits in the liver to severe liver scarring, called cirrhosis. Not everyone who drinks heavily will develop liver disease, but it is common. Studies show that up to 1 in 3 people with alcohol use disorder will develop some kind of ARLD.

Stopping alcohol use is the most important step in treating alcoholic hepatitis along with focusing on nutrition. Continuing to drink alcohol after being diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis greatly increases the risk of liver failure and death.

Products & Services

Symptoms

The most common symptom of alcoholic hepatitis is the skin and whites of the eyes turning yellow. This condition is called jaundice. Jaundice happens when a substance called bilirubin builds up in the body. Bilirubin is a yellow-colored waste product made when red blood cells break down.

Usually, the liver helps remove bilirubin from the blood and sends it out through the bile ducts into the intestines. But when the liver is damaged and can't work properly, bilirubin starts to build up in the blood, causing the yellow color. Yellowing of the skin might be harder to see depending on skin color.

Other symptoms include:

- Loss of appetite.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Belly tenderness.

- Fever. A fever caused by alcoholic hepatitis often is only a little higher than usual. This is called a low-grade fever. However, it is important to seek medical attention to rule out an infection.

- Tiredness and weakness.

- Pain in the upper right part of the abdomen where the liver is located. Because such pain can be caused by many other conditions, such as infection or gallstones, it's important to see a healthcare professional to find out the exact cause.

People with alcoholic hepatitis often don't get the nutrients they need from the food they eat. That condition is called malnutrition. It can happen because drinking large amounts of alcohol keeps people from being hungry. Heavy drinkers typically get most of their calories from alcohol.

Other symptoms that happen with advanced alcoholic hepatitis include:

- Fluid buildup in the belly, called ascites.

- Being confused and acting oddly due to a buildup of toxins, called hepatic encephalopathy. A healthy liver breaks down these toxins and gets rid of them.

- Kidney and liver failure.

- Bleeding in the digestive tract from enlarged veins that form in the esophagus or the stomach, called varices.

When to see a doctor

Alcoholic hepatitis is a serious, often deadly disease.

See a healthcare professional if you:

- Have symptoms of alcoholic hepatitis.

- Find it hard to manage how much you drink.

- Would like help changing your drinking habits.

Causes

Alcoholic hepatitis happens when heavy drinking causes harmful changes inside the liver. When the liver breaks down alcohol, it makes toxic substances that damage liver cells. These toxins also cause stress and swelling, called inflammation, in the liver.

When liver cells are damaged, the body's immune system tries to help, but this response can cause even more inflammation and damage. Alcohol also weakens the gut lining, allowing bacteria and their toxins to enter the liver from the digestive tract. This makes the inflammation worse.

Over time, fat can build up in the liver. When fat, inflammation and cell injury in the liver occur in someone with both metabolic dysfunction and significant alcohol use, the condition is called metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-associated liver disease (MetALD). This term reflects the overlap of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and alcohol-related injury.

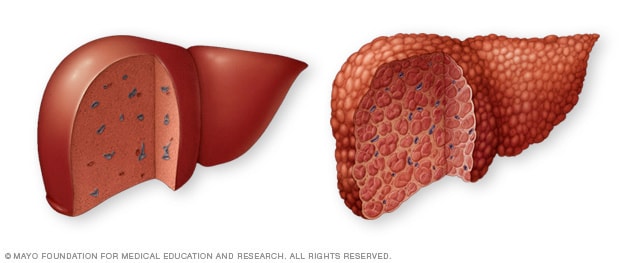

If the inflammation becomes severe enough to cause jaundice, and in some cases acute liver failure, the condition is called alcoholic hepatitis. As alcoholic hepatitis progresses, liver cells can die, bile can build up, and healthy tissue can be replaced by scar tissue, a condition called fibrosis in the early stages. Scarring may become more severe over time, leading to cirrhosis. Most people are diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis at an advanced stage of liver disease when fibrosis or cirrhosis is already present. Fibrosis may improve with alcohol abstinence, but cirrhosis is usually permanent.

Cirrhosis is the most advanced stage of alcohol-related liver disease. It prevents the liver from working properly, and it cannot be reversed. Some people have both alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis at the same time. Alcoholic hepatitis may be the first sign that cirrhosis has already developed. These changes keep the liver from doing its job properly.

Other substances besides alcohol also can inflame and damage the liver. This is called toxic hepatitis, which may result from certain medicines, herbal supplements or poisons. Alcoholic hepatitis is sometimes grouped under the broader category of toxic hepatitis, but most experts consider it a distinct condition caused specifically by alcohol.

If you have alcoholic hepatitis, other factors can make it worse, including:

- Other types of liver disease. Alcoholic hepatitis can make chronic liver diseases worse. For example, if you have hepatitis C and drink even a little alcohol, you're more likely to get liver scarring than if you don't drink.

- Not getting the right nutrition. Many people who drink heavily don't get enough nutrients because they tend not to eat a healthy diet. Alcohol keeps the body from using nutrients properly. Lack of nutrients can damage liver cells.

Risk factors

The main risk of alcoholic hepatitis comes from how much and how long a person drinks. One standard drink has about 14 grams of pure alcohol. This is the same as a 12-ounce beer, a 5-ounce glass of wine or a 1.5-ounce shot of liquor. For women, having 3 to 4 drinks a day for six months or longer raises the risk of alcoholic hepatitis. For men, having 4 to 5 drinks a day for six months or longer raises the risk of the disease. Not everyone who drinks this much will get the disease, but the chances are much higher.

Several factors can increase your risk of alcohol-related liver disease or make it worse, including:

- Sex. Women seem to have a higher risk of getting alcoholic hepatitis. That might be because of how alcohol breaks down in women's bodies.

- Weight. Heavy drinkers who are overweight might be more likely to get alcoholic hepatitis. And they might be more likely to go on to get liver scarring.

- Genes. Studies suggest that genes might be involved in liver disease that's caused by alcohol.

- Race and ethnicity. Black and Hispanic people might be at higher risk of alcoholic hepatitis.

- Binge drinking. Having five or more drinks in about two hours for men and four or more drinks in about two hours for women might raise the risk of alcoholic hepatitis.

- Acetaminophen use. Taking acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) while drinking alcohol can be dangerous for the liver. Even standard doses of acetaminophen may be harmful in people who drink heavily or already have liver disease, especially if taken repeatedly or in combination with alcohol.

- Bariatric surgery. After weight-loss surgeries such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy, the stomach processes alcohol differently. Because alcohol is absorbed faster and doesn't get broken down as much in the stomach, it reaches the small intestine more quickly. This causes blood alcohol levels to rise higher and faster than in people without surgery. As a result, even small amounts of alcohol can lead to unexpectedly high levels in the blood. This increases the risk of liver damage and rapid progression to cirrhosis.

Hepatitis means inflammation of the liver. Unlike viral hepatitis, such as hepatitis A, B or C, alcoholic hepatitis is not contagious. While viral hepatitis can be spread from person to person, alcoholic hepatitis is strictly related to alcohol use and individual risk factors.

Complications

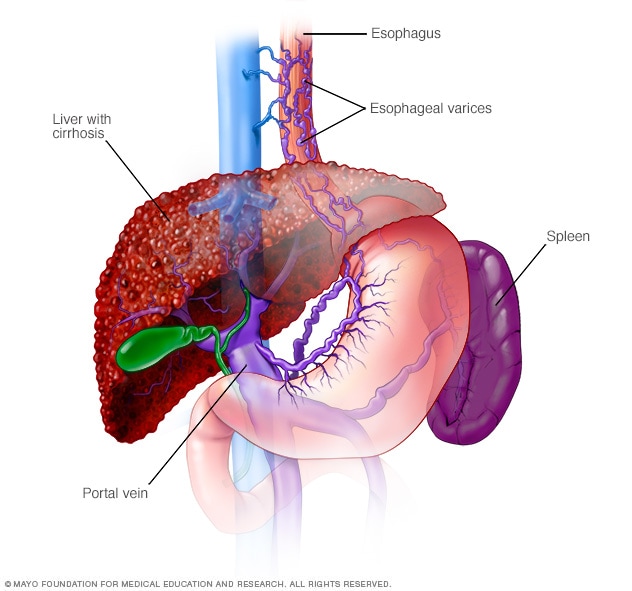

Esophageal varices

Esophageal varices

Esophageal varices are enlarged veins in the esophagus. They're often due to restricted blood flow through the portal vein. The portal vein carries blood from the intestine, pancreas and spleen to the liver.

Typical liver versus liver cirrhosis

Typical liver versus liver cirrhosis

A typical liver (left) shows no signs of scarring. In cirrhosis (right), scar tissue replaces healthy liver tissue.

Other health concerns, called complications, caused by alcoholic hepatitis can happen as a result of scar tissue on the liver or cirrhosis. Scar tissue can slow blood flow through the liver. That can raise pressure in a large blood vessel called the portal vein and cause a buildup of toxins.

Other complications may include:

-

Enlarged veins, called varices. When blood can't flow freely through the portal vein, the blood may back up into other blood vessels in the stomach. The blood also may go into blood vessels in the tube through which food passes from the throat to the stomach. That tube is called the esophagus.

Blood vessels in the stomach and esophagus have thin walls. They're likely to bleed if filled with too much blood. Heavy bleeding in the stomach or esophagus is life-threatening and needs medical care right away.

- Fluid buildup in the belly. This condition is called ascites (uh-SY-teez). When it happens, the fluid may get infected and need treatment with antibiotics. Ascites isn't life-threatening. But it often is a symptom of advanced alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis.

- Mental status changes. A liver that doesn't work well has trouble removing toxins from the body. The buildup of toxins can affect brain function. That condition is called hepatic encephalopathy. Symptoms include confusion, drowsiness and slurred speech. If it's not treated, hepatic encephalopathy can cause a coma and even death.

- Kidney failure. In alcoholic hepatitis, liver issues can trigger a chain reaction in the body that causes less blood to deliver oxygen to the kidneys. The kidneys begin to shut down, causing a life-threatening condition called hepatorenal syndrome. This leads to kidney failure, even though the kidneys themselves are not diseased.

- Cirrhosis. This scarring of the liver can lead to liver failure. Studies show that up to 70% of people with alcoholic hepatitis may develop cirrhosis over time if they do not stop drinking. Cirrhosis is a major risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma, the most common type of liver cancer. If you have cirrhosis, screening for liver cancer is recommended every six months.

-

Death. The outlook for people with alcoholic hepatitis depends on how severe the liver damage is and whether they stop drinking. For mild to moderate alcoholic hepatitis, the 30-day survival rate is high, between 80% to 100%. After one year, the risk of death rises slightly, with about 10% to 20% of people dying from complications of alcoholic hepatitis.

For severe alcoholic hepatitis, the chances of survival are much lower. The 30-day survival rate drops to about 50%. And if serious complications such as infections or kidney failure develop, the risk of dying goes up even more.

What if people have both hepatitis C and alcoholic hepatitis?

Having both hepatitis C and alcoholic hepatitis puts extra stress on the liver and can lead to more serious problems. People with both conditions are more likely to have liver failure, need to be hospitalized and have a higher risk of dying than people with alcoholic hepatitis alone.

The two diseases together can damage the liver faster and increase the risk of cirrhosis and even liver cancer. If you have both, it's very important to stop drinking alcohol and get treatment for hepatitis C, which may help improve your liver health and chances of recovery.

Prevention

To lower the risk of developing alcoholic hepatitis:

- Drink alcohol in moderation, if at all. For healthy adults, moderate drinking means up to one drink a day for women and up to two drinks a day for men. The only sure way to prevent alcoholic hepatitis is to not drink any alcohol. If you have had gastric bypass surgery, the limits are lower. Talk with your healthcare team about drinking alcohol.

- Protect yourself from hepatitis C. Hepatitis C is a liver disease caused by a virus. Without treatment, it can lead to cirrhosis. If you have hepatitis C and drink alcohol, you're much more likely to get cirrhosis than if you don't drink alcohol. Experts recommend that all adults 18 years and older be screened for hepatitis C.

-

Check before mixing medicines and alcohol. Ask your healthcare professional if it's safe to drink alcohol when taking your medicines. Read the warning labels on medicines you can get without a prescription.

Common medicines, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others), can make alcoholic hepatitis worse, especially when taken in high doses or in combination with alcohol. Even standard doses of acetaminophen may become harmful in people with liver disease, especially if acetaminophen is taken repeatedly or with ongoing alcohol use. This can lead to acute liver failure or make existing liver inflammation worse. If you have alcoholic hepatitis, talk to your healthcare team before taking acetaminophen or other nonprescription medicines.

Oct. 08, 2025