Overview

Encephalitis (en-sef-uh-LIE-tis) is inflammation of the brain. It can be caused by viral or bacterial infections, or by immune cells mistakenly attacking the brain. Viruses that can lead to encephalitis can be spread by insects such as mosquitos and ticks.

When inflammation is caused by an infection in the brain, it's known as infectious encephalitis. And when it's caused by the immune system attacking the brain, it's known as autoimmune encephalitis. Sometimes there is no known cause.

Encephalitis can sometimes lead to death. Getting diagnosed and treated right away is important because it's hard to predict how encephalitis may affect each person.

Products & Services

Symptoms

Encephalitis may cause many different symptoms including confusion, personality changes, seizures or trouble with movement. Encephalitis also may cause changes in sight or hearing.

Most people with infectious encephalitis have flu-like symptoms, such as:

- Headache.

- Fever.

- Aches in muscles or joints.

- Fatigue or weakness.

Typically, these are followed by more-serious symptoms over a period of hours to days, such as:

- Stiff neck.

- Confusion, agitation or hallucinations.

- Seizures.

- Loss of feeling or being unable to move certain areas of the face or body.

- Irregular movements.

- Muscle weakness.

- Trouble with speech or hearing.

- Loss of consciousness, including coma.

In infants and young children, symptoms also might include:

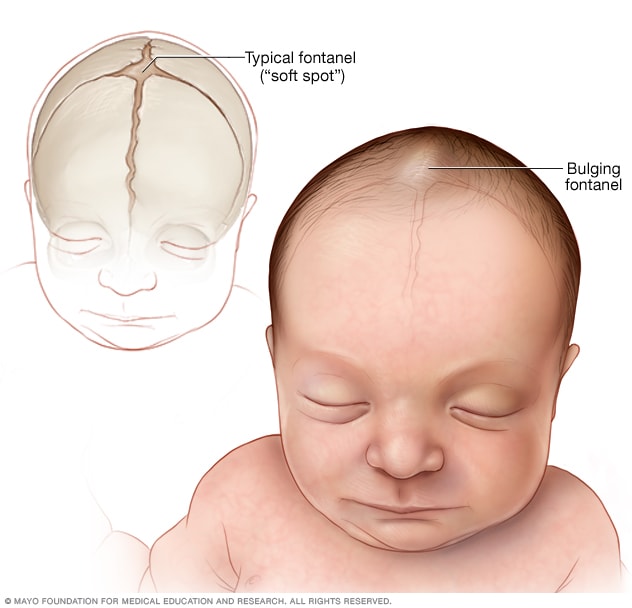

- Bulging of the soft spots of an infant's skull.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Stiffness affecting the whole body.

- Poor feeding or not waking for a feeding.

- Irritability.

Bulging fontanel

Bulging fontanel

One of the major signs of encephalitis in infants is a bulging of the soft spot, also known as the fontanel, of the baby's skull. Pictured here is the anterior fontanel. Other fontanels are found on the sides and back of an infant's head.

In autoimmune encephalitis, symptoms may develop more slowly over several weeks. Flu-like symptoms are less common but can sometimes happen weeks before more-serious symptoms start. Symptoms are different for everyone, but it's common for people to have a combination of symptoms, including:

- Changes in personality.

- Memory loss.

- Trouble understanding what is real and what is not, known as psychosis.

- Seeing or hearing things that aren't there, known as hallucinations.

- Seizures.

- Changes in vision.

- Sleep problems.

- Muscle weakness.

- Loss of sensation.

- Trouble walking.

- Irregular movements.

- Bladder and bowel symptoms.

When to see a doctor

Get medical care right away if you experience any of the more-serious symptoms associated with encephalitis. A bad headache, fever and change in consciousness require urgent care.

Infants and young children with any symptoms of encephalitis also need urgent care.

Causes

In about half of patients, the exact cause of encephalitis is not known.

In those for whom a cause is found, there are two main types of encephalitis:

- Infectious encephalitis. This condition usually occurs when a virus infects the brain. The infection may affect one area or be widespread. Viruses are the most common causes of infectious encephalitis, including some that can be passed by mosquitoes or ticks. Very rarely, encephalitis may be caused by bacteria, fungus or parasites.

- Autoimmune encephalitis. This condition occurs when your own immune cells mistakenly attack the brain or make antibodies targeting proteins and receptors in the brain. The exact reason why this happens is not completely understood. Sometimes autoimmune encephalitis can be triggered by cancerous or noncancerous tumors, known as paraneoplastic syndromes of the nervous system. Other types of autoimmune encephalitis such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) can be triggered by an infection in the body. This is known as post-infectious autoimmune encephalitis. In many instances, no trigger for the immune response is found.

Common viral causes

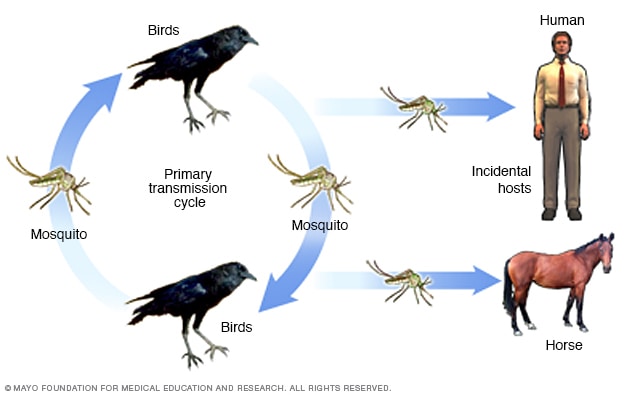

West Nile virus transmission cycle

West Nile virus transmission cycle

When a mosquito bites an infected bird, the virus enters the mosquito's bloodstream and eventually moves into its salivary glands. When an infected mosquito bites an animal or a human, known as the host, the virus is passed into the host's bloodstream, where it may cause serious illness.

The viruses that can cause encephalitis include:

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV). Both HSV type 1 and HSV type 2 can cause encephalitis. HSV type 1 causes cold sores and fever blisters around the mouth, and HSV type 2 causes genital herpes. Encephalitis caused by HSV type 1 is rare but can result in significant brain damage or death.

- Other herpes viruses. These include the Epstein-Barr virus, which commonly causes infectious mononucleosis, and the varicella-zoster virus, which commonly causes chickenpox and shingles.

- Enteroviruses. These viruses include the poliovirus and the coxsackievirus, which usually cause an illness with flu-like symptoms, eye inflammation and abdominal pain.

- Mosquito-borne viruses. These viruses can cause infections such as West Nile, La Crosse, St. Louis, western equine and eastern equine encephalitis. Symptoms of an infection might appear within a few days to a couple of weeks after exposure to a mosquito-borne virus.

- Tick-borne viruses. The Powassan virus is carried by ticks and causes encephalitis in the Midwestern United States. Symptoms usually appear about a week after a bite from an infected tick.

- Rabies virus. Infection with the rabies virus, which is usually transmitted by a bite from an infected animal, causes a rapid progression to encephalitis once symptoms begin. Rabies is a rare cause of encephalitis in the United States.

Risk factors

Anyone can develop encephalitis. Factors that may increase the risk include:

- Age. Some types of encephalitis are more common or more serious in certain age groups. In general, young children and older adults are at greater risk of most types of viral encephalitis. Similarly, some forms of autoimmune encephalitis are more common in children and young adults, whereas others are more common in older adults.

- Weakened immune system. People who have HIV/AIDS, take immune-suppressing medicines or have another condition causing a weakened immune system are at increased risk of encephalitis.

- Geographical regions. Mosquito- or tick-borne viruses are common in particular geographical regions.

- Season of the year. Mosquito- and tick-borne diseases tend to be more common in summer in many areas of the United States.

- Autoimmune disease. People who already have an autoimmune condition may be more prone to develop autoimmune encephalitis.

- Smoking. Smoking increases the chances of developing lung cancer, which in turn increases the risk of developing paraneoplastic syndromes including encephalitis.

Complications

The complications of encephalitis vary, depending on factors such as:

- Your age.

- The cause of your infection.

- The severity of your initial illness.

- The time from disease onset to treatment.

People with relatively mild illness usually recover within a few weeks with no long-term complications.

Complications of serious illness

Inflammation can injure the brain, possibly resulting in a coma or death.

Other complications may last for months or may be permanent. Complications can vary widely and can include:

- Fatigue that doesn't go away.

- Weakness or lack of muscle coordination.

- Personality changes.

- Memory problems.

- Hearing or vision changes.

- Trouble with speech.

Prevention

The best way to prevent viral encephalitis is to take precautions to avoid exposure to viruses that can cause the disease. Try to:

- Practice good hygiene. Wash hands often and thoroughly with soap and water, especially after using the toilet and before and after meals.

- Don't share utensils. Don't share tableware and drinks.

- Teach your children good habits. Make sure they practice good hygiene and avoid sharing utensils at home and school.

- Get vaccinations. Keep your own and your children's vaccinations current. Before traveling, talk to your healthcare professional about recommended vaccinations for different destinations.

Protection against mosquitoes and ticks

To minimize your exposure to mosquitoes and ticks:

- Dress to protect yourself. Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants outside. This is especially important if you're outside between dusk and dawn when mosquitoes are most active. It's also important when you're in a wooded area with tall grasses and shrubs where ticks are more common.

- Apply mosquito repellent. Chemicals such as DEET can be applied to both the skin and clothes. To apply repellent to your face, spray it on your hands and then wipe it on your face. If you're using both sunscreen and a repellent, apply sunscreen first.

- Use insecticide. The Environmental Protection Agency recommends the use of products containing permethrin, which repels and kills ticks and mosquitoes. These products can be sprayed on clothing, tents and other outdoor gear. Permethrin shouldn't be applied to the skin.

- Avoid mosquitoes. Stay away from places where mosquitoes are most common. If possible, don't do outdoor activities from dusk till dawn when mosquitoes are most active. Repair broken windows and screens.

- Get rid of water sources outside your home. Eliminate standing water in your yard, where mosquitoes can lay their eggs. Common places include flowerpots or other gardening containers, flat roofs, old tires, and clogged gutters.

- Look for outdoor signs of viral disease. If you notice sick or dying birds or animals, report your observations to your local health department.

Protection for young children

Insect repellents aren't recommended for use on infants younger than 2 months of age. Instead, cover an infant carrier or stroller with mosquito netting.

For older infants and children, repellents with 10% to 30% DEET are considered safe. Products containing both DEET and sunscreen aren't recommended for children. This is because reapplying for sunscreen protection can expose the child to too much DEET.

Tips for using mosquito repellent with children include:

- Always assist children with the use of mosquito repellent.

- Spray on clothing and exposed skin.

- Apply the repellent when outdoors to lessen the risk of inhaling the repellent.

- Spray repellent on your hands and then apply it to your child's face. Take care around the eyes and ears.

- Don't use repellent on the hands of young children who may put their hands in their mouths.

- Wash treated skin with soap and water when you come indoors.