Overview

Clostridioides difficile (klos-TRID-e-oi-deez dif-uh-SEEL) is a bacterium that causes an infection of the colon, the longest part of the large intestine. Symptoms can range from diarrhea to life-threatening damage to the colon. The bacterium is often called C. difficile or C. diff.

Illness from C. difficile often occurs after using antibiotic medicines. It mostly affects older adults in hospitals or in long-term care settings. People not in care settings or hospitals also can get C. difficile infection. Some strains of the bacterium that can cause serious infections are more likely to affect younger people.

The bacterium used to be called Clostridium (klos-TRID-e-um) difficile.

Products & Services

Symptoms

Symptoms often begin within 5 to 10 days after starting an antibiotic. But symptoms can occur as soon as the first day or up to three months later.

Mild to moderate infection

The most common symptoms of mild to moderate C. difficile infection are:

- Watery diarrhea three or more times a day for more than one day.

- Mild belly cramping and tenderness.

Severe infection

People who have a severe C. difficile infection tend to lose too much bodily fluid, a condition called dehydration. They might need to be treated in a hospital for dehydration. C. difficile infection can cause the colon to become inflamed. It sometimes can form patches of raw tissue that can bleed or make pus. Symptoms of severe infection include:

- Watery diarrhea as often as 10 to 15 times a day.

- Belly cramping and pain, which may be severe.

- Fast heart rate.

- Loss of fluids, called dehydration.

- Fever.

- Nausea.

- Increased white blood cell count.

- Kidney failure.

- Loss of appetite.

- Swollen belly.

- Weight loss.

- Blood or pus in the stool.

C. difficile infection that is severe and sudden can cause the colon to become inflamed and get larger, called toxic megacolon. And it can cause a condition called sepsis where the body's response to an infection damages its own tissues. People who have toxic megacolon or sepsis are admitted to an intensive care unit in the hospital. But toxic megacolon and sepsis aren't common with a C. difficile infection.

When to see a doctor

Some people have loose stools during or shortly after antibiotic therapy. This may be caused by C. difficile infection. Make a health care appointment if you have:

- Three or more watery stools a day.

- Symptoms lasting more than two days.

- A new fever.

- Severe belly pain or cramping.

- Blood in your stool.

Causes

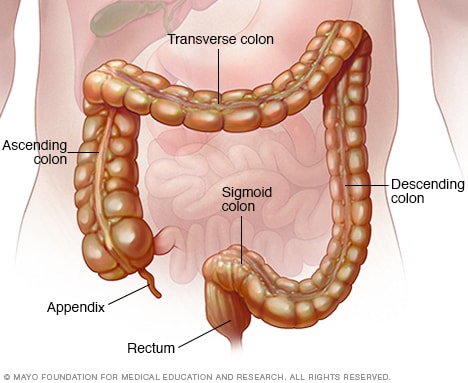

Colon and rectum

Colon and rectum

The colon, also called the large intestine, is a long tubelike organ in the abdomen. The colon carries waste to be expelled from the body. The rectum makes up the last several inches of the large intestine.

C. difficile bacteria enter the body through the mouth. They can begin reproducing in the small intestine. When they reach the part of the large intestine, called the colon, the bacteria can release toxins that damage tissues. These toxins destroy cells and cause watery diarrhea.

Outside the colon, the bacteria aren't active. They can live for a long time in places such as:

- Human or animal feces.

- Surfaces in a room.

- Unwashed hands.

- Soil.

- Water.

- Food, including meat.

When bacteria once again find their way into a person's digestive system, they become active again and cause infection. Because C. difficile can live outside the body, the bacteria spread easily. Not washing hands or cleaning well make it easy to spread the bacteria.

Some people carry C. difficile bacteria in their intestines but never get sick from it. These people are carriers of the bacteria. They can spread infections without being sick.

Risk factors

People who have no known risk factors have gotten sick from C. difficile. But certain factors increase the risk.

Taking antibiotics or other medicines

The intestines house a wide range of bacteria. Many of them help protect the body from infection. Antibiotics that treat an infection tend to destroy some of the helpful bacteria in the body as well as the bacteria causing the infection.

Without enough helpful bacteria to keep it in check, C. difficile can grow out of control quickly. Any antibiotic can cause C. difficile infection. But the antibiotics that most often lead to C. difficile infection include:

- Clindamycin.

- Cephalosporins.

- Penicillins.

- Fluoroquinolones.

Taking a proton pump inhibitor, a type of medicine used to cut stomach acid, also may increase the risk of C. difficile infection.

Staying in a health care setting

Most C. difficile infections occur in people who are in or have recently been in health care settings. These include hospitals, nursing homes and long-term care facilities. These are places where germs spread easily, antibiotic use is common and people's health puts them at high risk of getting an infection. In hospitals and nursing homes, C. difficile spreads on:

- Hands.

- Cart handles.

- Bedrails.

- Bedside tables.

- Toilets and sinks.

- Stethoscopes, thermometers or other medical tools.

- Telephones.

- Remote controls.

Having a serious illness or medical procedure

Certain medical conditions or procedures can up the risk of getting a C. difficile infection, including:

- Inflammatory bowel disease.

- Weakened immune system from a medical condition or treatment such as chemotherapy.

- Chronic kidney disease.

- Procedures on the digestive tract.

- Other surgery of the stomach area.

Other risk factors

Older age is a risk factor. In one study, the risk of becoming infected with C. difficile was 10 times greater for people age 65 and older compared with younger people.

Having one C. difficile infection increases the chance of having another one. The risk increases with each infection.

Complications

Complications of C. difficile infection include:

- Loss of fluids, called dehydration. Severe diarrhea can lead to a serious loss of fluids and minerals called electrolytes. This makes it hard for the body to work as it should. It can cause blood pressure to drop so low as to be dangerous.

- Kidney failure. In some cases, dehydration can occur so quickly that the kidneys stop working, called kidney failure.

Toxic megacolon. In this rare condition, the colon can't get rid of gas and stool. This causes it to enlarge, called megacolon. Untreated, the colon can burst.

Bacteria also may enter the bloodstream. Toxic megacolon may be fatal. It needs emergency surgery.

- A hole in the large intestine, called bowel perforation. This rare condition results from damage to the lining of the colon or occurs after toxic megacolon. Bacteria spilling from the colon into the hollow space in the middle of the body, called the abdominal cavity, can lead to a life-threatening infection called peritonitis.

- Death. Serious C. difficile infection can quickly become fatal if not treated promptly. Rarely, death can occur with mild to moderate infection.

Prevention

To protect against C. difficile, don't take antibiotics unless you need them. Sometimes, you may get a prescription for antibiotics to treat conditions not caused by bacteria, such as viral illnesses. Antibiotics don't help infections caused by viruses.

If you need an antibiotic, ask if you can get a prescription for a medicine that you take for a shorter time or is a narrow-spectrum antibiotic. Narrow-spectrum antibiotics target a limited number of bacteria types. They're less likely to affect healthy bacteria.

To help prevent the spread of C. difficile, hospitals and other health care settings follow strict rules to control infections. If you have a loved one in a hospital or nursing home, follow the rules. Ask questions if you see caregivers or other people not following the rules.

Measures to prevent C. difficile include:

Hand-washing. Health care workers should make sure their hands are clean before and after treating each person in their care. For a C. difficile outbreak, using soap and warm water is better for cleaning hands. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers don't destroy C. difficile spores.

Visitors to health care facilities also should wash their hands with soap and warm water before and after leaving rooms or using the bathroom.

- Contact precautions. People who are hospitalized with C. difficile infection have a private room or share a room with someone who has the same illness. Hospital staff and visitors wear disposable gloves and isolation gowns while in the room.

- Thorough cleaning. In any health care setting, all surfaces should be carefully disinfected with a product that has chlorine bleach. C. difficile spores can survive cleaning products that don't have bleach.

Sept. 01, 2023