Overview

Anthrax is a rare but serious illness caused by a spore-forming bacterium, called Bacillus anthracis. In the body, the spores form poisons that can destroy tissues. Anthrax mainly affects farm animals and wild game. People can get infected through contact with sick animals.

Anthrax does not spread from person to person like a cold does. But anthrax spores can enter the body through a cut or scrape on the skin. Rarely, anthrax can be spread from someone who has an anthrax skin sore. Eating meat that has the germs or breathing in the spores also can cause anthrax.

Symptoms depend on how you're infected. Anthrax symptoms can include skin sores, vomiting and shock. Quick treatment with antibiotics can cure most anthrax infections. Inhaled anthrax is harder to treat and can be fatal.

Anthrax is rare in the United States. But the illness is a concern because the germs have been used in terrorist attacks, called bioterrorism, in the country.

Symptoms

There are four common ways to be infected with anthrax. Each has its own symptoms. Most often, symptoms start within seven days of contact with the bacteria. But sometimes, symptoms of anthrax can take weeks to appear.

Cutaneous anthrax

A skin-related anthrax infection, called cutaneous anthrax infection, enters the body through the skin. This most often is through a cut or other sore. It's the most common way to get the disease. It's also the mildest form. With treatment, cutaneous anthrax rarely is fatal.

Symptoms can include:

- A raised, itchy bump that looks like an insect bite. It soon becomes a painless sore with a black center.

- Fever.

- Swelling around the sore and nearby lymph nodes. The swelling might cause trouble with breathing, eating or drinking if the sore is on the face, neck or chest.

Cutaneous anthrax

Anthrax can happen when spores go through the skin, most often through an open sore. The infection starts as a raised, sometimes itchy, bump that looks like an insect bite. But within a day or two, the bump becomes an open, most often painless sore with a black center.

Gastrointestinal anthrax

A gastrointestinal anthrax infection results from eating meat from an infected animal that isn't cooked well enough. It can affect the throat, esophagus, stomach and intestines. Symptoms may include:

- Nausea.

- Vomiting that might be bloody.

- Belly pain.

- Headache.

- Loss of appetite.

- Fever.

- Severe, bloody diarrhea in the later stages of the disease.

- Sore throat and painful swallowing.

- Swollen neck.

Inhalation anthrax

Inhalation anthrax comes from breathing in anthrax spores. It's the deadliest form of the disease. It's often fatal, even with treatment. Symptoms include:

- Flu-like symptoms for a few hours or days, such as sore throat, fever, tiredness and muscle aches.

- Chest discomfort.

- Shortness of breath.

- Nausea.

- Coughing up blood.

- Painful swallowing.

- High fever.

- Shock. This causes the collapse of the system that carries oxygen to cells, called the circulatory system.

- Irritation and swelling, called inflammation, of the tissues around the brain and the spinal cord. This is called meningitis.

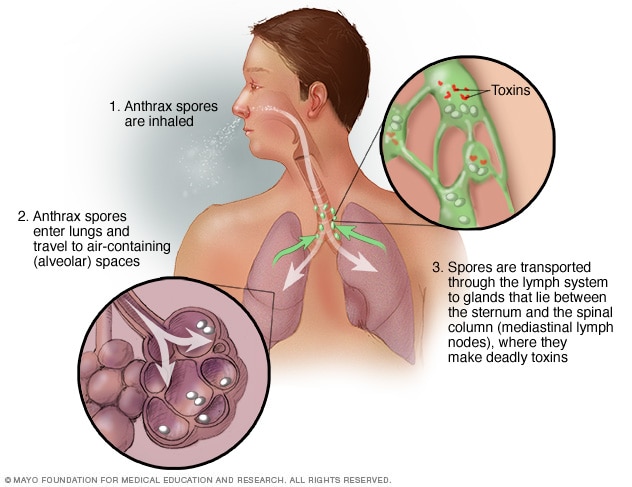

Inhalation anthrax

This shows how the spores that cause anthrax that's breathed in, called inhalation anthrax, enter and affect the body. This is the deadliest form of anthrax.

Injection anthrax

This way of getting anthrax infection so far has been reported only in Europe. It comes from injecting illicit drugs.

Early symptoms include:

- Bumps that might itch at the area of injection.

- Swelling around the sore.

When to see a doctor

Many common illnesses start with symptoms like those of the flu. The chances that your sore throat and aching muscles are due to anthrax are very small.

If you think you may have been in contact with anthrax, seek medical care right away. If you get symptoms of the disorder after being in contact with animals or animal products in parts of the world where anthrax is common, seek medical care as soon as possible. Early diagnosis and treatment are needed.

Causes

Anthrax spores are formed by anthrax bacteria that live in soil in most parts of the world. The spores can be inactive for years until they enter a host. Common hosts for anthrax include wild animals or farm animals, such as sheep, cattle, horses and goats.

Although rare in the United States, anthrax is still common in farmed areas in other countries where animals are not regularly vaccinated against anthrax. These include Central America and South America, sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia and southwestern Asia, southern and Eastern Europe, and the Caribbean.

Most human cases of anthrax come from contact with infected animals or their meat or hides.

One of the few known times that people got anthrax that wasn't from infected animals was a terrorist attack that used anthrax as a weapon, called bioterrorism. This was in the United States in 2001. Twenty-two people got anthrax after contact with powdered spores sent through the mail. Five of those infected died.

Other anthrax outbreaks not linked to infected animals have been linked to injecting illicit drugs.

Risk factors

To get anthrax, you must come in contact with anthrax spores. This is more likely if you:

- Are in the military and in an area where the risk of being exposed to anthrax is high.

- Work with anthrax in a laboratory setting.

- Handle animal skins, furs or wool from areas with a lot of anthrax.

- Work in veterinary medicine with farm animals.

- Handle or dress game animals.

- Inject drugs such as heroin.

Complications

The most serious complications of anthrax include:

- The body not being able to fight the infection. This starts a chain reaction called sepsis that can lead to damage of more than one organ system.

- Irritation and swelling, called inflammation, of the membranes and fluid that cover the brain and spinal cord. This can lead to bleeding, called hemorrhagic meningitis, and death.

- Shock. This causes the collapse of the system that carries oxygen to cells, called the circulatory system.

Prevention

To prevent infection after being exposed to anthrax spores, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests:

- A 60-day treatment with antibiotics.

- A three-dose series of anthrax vaccine.

- Sometimes, treatment with monoclonal antibodies, raxibacumab and obiltoxaximab.

Anthrax vaccine

An anthrax vaccine is for certain groups of people. The vaccine doesn't have live bacteria and can't lead to infection. But the vaccine can cause side effects. They include soreness at the site of the vaccine and allergic reactions.

The vaccine isn't meant for everyone. It's for people in the military, scientists working with anthrax, and people in other high-risk jobs who handle animals or animal products. Protection involves getting five shots over 18 months and yearly boosters.

The vaccine also is approved for use in people ages 18 through 65 who have been in contact with anthrax from, for example, a terrorist attack using anthrax spores.

Avoiding infected animals

If you live or travel in a country where anthrax is common and herd animals aren't vaccinated, avoid contact with livestock and animal skins as much as possible. Also don't eat meat that hasn't been cooked all the way.