May 29, 2018

Up to 10 percent of hospitalized trauma patients have rib fractures. Flail chest — defined as two or more contiguous rib fractures with two or more breaks per rib — is one of the most serious of these injuries and is often associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. It occurs when a portion of the chest wall is destabilized, usually from severe blunt force trauma. This alters the mechanics of breathing so that the floating segment of chest wall and soft tissue moves paradoxically in the opposite direction from the rest of the rib cage.

Until recently, ribs fractures were allowed to heal on their own or treated with continuous positive pressure ventilation. Now, surgical stabilization of fractured ribs is becoming more widely accepted, especially for flail chest, according to Henry J. Schiller, M.D., a trauma surgeon at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota.

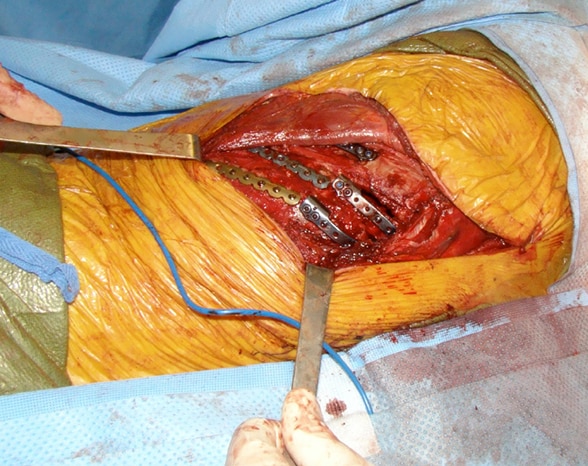

Estabilización quirúrgica de fractura de costillas

Estabilización quirúrgica de fractura de costillas

Estabilización quirúrgica de fractura de costillas con placas y tornillos de titanio

Mayo Clinic began practicing rib fracture stabilization for adult patients 2009. In 2014, Dr. Schiller and colleagues published a study in the European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery showing that the procedure significantly improved forced vital capacity in patients with flail chest. Other research, including a 2013 retrospective meta-analysis, found that rib fracture stabilization resulted in better outcomes overall, including decreased ventilator and ICU days and decreased rates of tracheostomy and pneumonia. The review was published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Rib fracture fixation benefits

Decreased risk of pneumonia is one of the main reasons for surgical rib stabilization, especially in older patients, Dr. Schiller says. "The risk of dying of rib fractures increases twofold at age 55, fivefold at 65 and sevenfold at 75. An older adult on a breathing tube with pneumonia may not survive."

Long-term pain management is another benefit. "The more unstable the fractures, the more it hurts and the more difficult for patients to breathe and maintain adequate pulmonary hygiene," he says. "We use nerve blocks and epidural anesthetics, which can provide temporary pain relief, but rib pain lasts for weeks, and none of the nonsurgical options are ideal for managing it."

Still, only a small minority of patients with serious rib fractures are offered surgical stabilization.

"As we've gained experience, we've learned which ribs should be fixed, and it's about 1 in 10," Dr. Schiller says. "Initially, we focused only on flail chest, but now we offer surgery to people with simple, non-flail rib fractures if their vital capacity is less than 1500 on serial exams and their chest X-ray lung volumes are decreasing. We've learned that even people with nondisplaced fractures that don't seem bad on CT scans can actually have very unstable fractures. We think some fractures may just appear to be simple because the patient is lying flat during imaging and not moving. Then, once we go in, we realize that these simple fractures have more mobility than we thought."

Despite this, the tendency is to manage rib fractures nonoperatively, mainly because of the risk of infection. "If the plates become infected, we have to remove them, leading to multiple operations. The rule of thumb for rib fracture stabilization is to operate within seven days of the injury because the risk of infection is lower and pain is markedly improved compared to repair delayed beyond seven days. Sometimes we try to operate the day a patient is admitted," Dr. Schiller says.

A flail chest case study

In 2016, a critically injured, 60-year-old farm worker presented to the emergency department at Mayo Clinic's campus in Minnesota. Among other serious injuries, he had a flail chest with four or five ribs in each flail segment.

"He was breathing on his own but was in so much pain, he wasn't moving much air into his chest," Dr. Schiller says. "He had declining X-ray lung volumes, so we knew we had to fix his ribs."

But which ribs? One nagging question is whether all the ribs in a flail should be fixed. Dr. Schiller was senior author of a study published in 2016 in World Journal of Surgery that looked at 43 patients who underwent rib fracture stabilization procedures between 2009 and 2013. Twenty-three had complete flail chest stabilization and 47 underwent partial stabilization. There was no difference in hospital length of stay, chest wall deformity, narcotic use or pulmonary function tests between the two groups, leading the authors to suggest that the additional surgery required for complete stabilization was unnecessary.

The severely injured farm worker proved to be an exception. "He had flail ribs in both the front and back of his chest under the shoulder blade. In our paper, it seemed that if we fixed one or two of the flails in the segment, the outcomes were equivalent. So we thought we could fix the ribs in the back, which would require just one incision and be less complicated than fixing them in the front, where you are dealing with the chest muscles inserting directly on the ribs," Dr. Schiller explains.

The ribs were repaired in a staged approach — first the left side where the pain was greater and then the right side. But once the patient was off the ventilator, he experienced severe pain in the front of his chest that he wasn't able to localize to one side or the other.

Dr. Schiller explains: "We took him back to the operating room and fixed all the ribs in front and the back in a staged approach. It was an unusual situation because we should have been able to repair the ribs in the back only with good results. The patients in our study had ribs in the front of the chest that were broken, but not displaced. This patient had terrible displacement in the front and back, and both sides had to be repaired to stabilize the chest wall and obtain pain relief."

The patient had a lengthy recovery. He was debilitated, and there was a delayed finding of an abdominal injury that didn't show up on initial imaging. Now, however, he is doing well and expected to return to full functioning.

For referring hospitals

Dr. Schiller says any patient who has a flail chest seen on plain X-ray or CT should be sent to a center for rib fracture stabilization within the seven-day window to reduce the risk of infection and optimize pain relief.

"If providers aren't sure a patient has flail chest but see the lungs deteriorating and smaller lung volumes and most important, the diaphragm is obscured on serial chest X-rays, then that patient should have rib fracture stabilization, if it can be tolerated," he says. "The procedure requires unique skills, and Mayo Clinic can offer that. We also have an excellent pain control protocol at all Mayo sites, including all affiliated sites. If patients aren't candidates for surgery, we have other good options."

For more information

Said SM, et al. Surgical stabilization of flail chest: The impact on postoperative pulmonary function. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. 2014;40:501.

Slobogean GP, et al. Surgical fixation vs nonoperative management of flail chest: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2013;216:302.

Nickerson TP, et al. Outcomes of complete versus partial surgical stabilization of flail chest. World Journal of Surgery. 2016;40:236.