Aug. 08, 2020

"The only constant in life is change." These words by the Greek philosopher Heraclitus are no less true today than they were 2,500 years ago. The year 2020 has already brought about unprecedented change in personal, professional, academic and social lives, putting the ability to cope with the constant change to test. Mayo Clinic's endocrinology practice went through multiple phases of uncertainty and change from the beginning of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. How did each of our subspecialty groups work through these challenges, and what did we learn from our initial response plans?

Overall practice changes

Institutional and departmental priorities remained true to Mayo Clinic values. The goals of our contingency plan were to ensure the safety of patients and staff while accommodating their clinical needs, and to maximize availability of staff, space and supplies needed to meet a potential surge of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. By the end of February 2020, plans were in place to meet the challenges ahead. Starting mid-March, all Mayo Clinic sites deferred elective inpatient and outpatient visits and procedures, as well as patient research visits to the Clinical Research and Trials Unit. Endocrinology staff members were asked to review their scheduled patients to determine whether a face-to-face visit was clinically necessary or whether visits could be changed to a virtual platform (either phone or video visit, collectively referred to as telehealth) or deferred for eight to 12 weeks.

After the doubling times for the rate of new infections in our communities exceeded COVID-19-related length of hospital stay, the practice was able to start the slow process of resuming face-to-face visits, while following institutional safety guidelines and procedures. At the time of writing in early summer, the practice continues to move toward a phased ramp-up of clinical and research activities.

Thyroid and endocrine neoplasia

Thyroid nodule fine-needle aspiration procedures were initially paused for two to three weeks. Upon resumption of these procedures, plans were in place to screen all patients for SARS-CoV-2 using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on nasal swabs.

Patients with endocrine neoplasia, including advanced thyroid cancer, generally continued their therapy treatments without interruption. The care for many patients necessitated continued face-to-face visits. Patients receiving oral chemotherapy continued follow-up via virtual visits. Radiation treatments with the Department of Radiation Oncology continued at a nearly completely uninterrupted pace.

Surgical interventions were reserved for patients with emergent or urgent cancer-related disease, with indications reviewed on a case-by-case basis by a specialty review committee. "As most of thyroid cancer operations are not urgent, these procedures were delayed by four to eight weeks, when clinically appropriate," reports John C. Morris III, M.D., with Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota. Ablation procedures were also paused for about four to six weeks.

"Evidence soon emerged that patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy and with active COVID-19 infection have worse outcomes. This led our group to institute screening for SARS-CoV-2 prior to chemotherapy infusions," adds Mabel Ryder, M.D., with Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota.

Diabetes and metabolism

Using secure online tools, patients were able to download their home glucometer records and make them available to be reviewed by their providers at the time of the virtual follow-up visit. Similarly, patients using an insulin pump (continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, or CSII, technology) were able to download their data online and share it with their Mayo Clinic providers to make educated clinical decisions.

Patient education, which is a cornerstone in diabetes management, continued virtually as well. "We provided an array of individual teaching sessions ranging from basic glucose monitoring and insulin injection education to more advanced insulin dose adjustment skills via phone or video," confirms Alexandra M. Herzog, M.S.N., R.N., with Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota "We were also able to provide electronic copies of Mayo Clinic patient education material and video links through the secure patient message portal," adds Heather A. Wesely, R.N., CDCES, with Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota.

Outpatient nutrition

The outpatient obesity practice had to pivot rapidly to accommodate patients' needs. All in-person visits were initially halted for a period of time. New patient consults were seen via a video visit, which was quite well received by most staff. Our partners in dietetics and behavioral psychology also offered virtual visits.

During the pandemic, with many patients working from home, it was not uncommon to hear about challenges due to changes in routine, eating habits and physical activity. "Patients were often disappointed by their weight trend during this time," recognizes Meera Shah, M.B., Ch.B., with Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota. Several were concerned about continued eligibility for bariatric surgery, as there are set criteria in place, guided by insurance companies, such as the need for consecutive months of medically supervised weight loss. These patients were given counseling over the phone by the bariatric nurse team, to include ways to utilize employee resources for weight management.

The patients who had bariatric surgery, particularly the patients who had undergone surgery in the last three months, received a phone call from our advanced practitioner. Lab work had to be delayed, but if there were any concerning symptoms reported during the phone visit, the patients were asked to seek urgent care locally. The patients with medically complicated obesity already on a weight-loss medication were followed up virtually. When available, patients reported their home blood pressure and weight measurements.

Metabolic bone disease and parathyroid

Criterios de necesidad médica

Criterios de necesidad médica

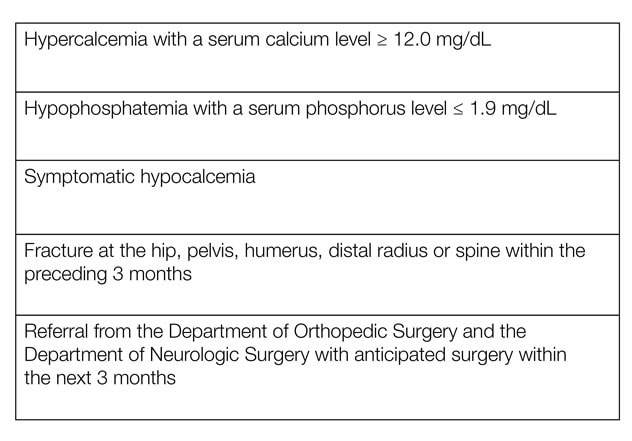

Tabla. Criterios del Grupo Central de Salud Ósea para priorizar las visitas presenciales y de telesalud

Our Bone Core Group delineated the criteria for medical necessity to accommodate patients for face-to-face or telehealth visits.

"In addition, a significant challenge surfaced for patients requiring a visit to a health care facility to obtain intravenous or subcutaneous treatment for osteoporosis or other metabolic bone diseases," notes Matthew T. Drake, M.D., Ph.D., with Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota. "We thus collectively recommended that patients receiving denosumab should be accommodated no later than seven months from their previous dose; otherwise consideration should be given to changing to another agent such as a bisphosphonate." Patients receiving romosozumab should be scheduled as close to monthly as possible; if there is a delay of two months or greater from the previous dose, physicians should similarly consider changing to another agent such as a bisphosphonate. Additional options, such as home delivery and administration, have subsequently become available to patients. Dr. Drake spearheaded the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research expert panel that provided recommendations for osteoporosis management in the era of COVID-19, as published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Endocrine and diabetes hospital service

Almost all hospital consultations and patient rounds were performed virtually. "Face-to-face visits were reserved for patients in whom physical examination or in-person conversation was essential to guide their care," reports Catherine D. Zhang, M.D., with Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota. "For instance, we were able to obtain significant in-person information when we visited with a patient with severe hypoglycemic episodes of unclear etiology," adds Natalia Genere, M.D., with Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota.

The frequency of follow-up visits did not change; the challenge mostly lied in the coordination of the video visits given the unpredictable availability of patients, caregivers and nursing staff. "This was particularly challenging for patients who were not familiar with the technology and required an institutionally provided touch-screen tablet to complete the visit," states Dr. Genere.

Teaching rounds continued virtually with no interruption to the educational value of the hospital service. Daily teaching sessions by the staff consultants and senior fellows continued using online meeting platforms.

Hospital Nutrition Support Service

The Nutrition Support Service (NSS), which oversees hospitalized patients requiring nutritional support, worked remotely during an extended period. Twice daily our entire team (staff physician, trainee, dietitian, nurse and pharmacist) called into a shared phone number to discuss each patient. Individual patients' clinical course, nutrition program, fluid balance and laboratory data were reviewed using the NSS-specific platform within the electronic health record (EHR) in an effort to determine if the parenteral or enteral nutrition remained appropriate. The staff physician and trainee discussed selected nutrition topics or manuscripts by phone throughout the day. "Twice daily rounds allowed our team to stay in good contact and were the most efficient way to streamline review of new consults received through the day," reports M. Molly McMahon, M.D., with Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition at Mayo Clinic's campus in Rochester, Minnesota. "The pandemic also led us to be mindful of any aerosol-producing procedure, such as placement of nasal feeding tubes or swallow studies."

The team reviewed the Nutrition Therapy in the Patient With COVID-19 Disease Requiring ICU Care recommendations reviewed and approved by the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Of note, obesity is a major risk factor for COVID-19. The administration of nutrition to these patients should adhere to the basic principles of critical care nutrition. However, several unique challenges arise. Some patients require prone positioning to improve oxygenation and increase bronchial secretion clearance. Most patients in this setting tolerate enteral nutrition administered into the stomach, but a post-pyloric placement of the feeding tube may be needed. The head of the bed should be elevated (reverse Trendelenburg position) to at least 10 to 25 degrees to decrease the risk of aspiration. In addition, hypercoagulability can make placement of central vascular access problematic. We worked with institutional colleagues to create a contingency plan in the event of a shortage of enteral pumps; this included prioritizing patients requiring small bowel feeding and those with symptoms of gastric feeding intolerance.

For more information

Lal S, et al. Considerations for the management of home parenteral nutrition during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: A position paper from the Home Artificial Nutrition and Chronic Intestinal Failure Special Interest Group of ESPEN. Clinical Nutrition. 2020;39:1988.

Yu EW, et al. Osteoporosis management in the era of COVID-19. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2020;35:1009.

Martindale R, et al. Nutrition therapy in the patient with COVID-19 disease requiring ICU care. American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.