Diagnosis

Thyroid cancer FAQs

Endocrinologist Mabel Ryder, M.D., answers the most frequently asked questions about thyroid cancer.

Hi. I'm Dr. Mabel Ryder, an endocrinologist at Mayo Clinic, and I'm here to answer some of the important questions you may have about thyroid cancer.

What is the next step after a thyroid cancer diagnosis?

The next step after thyroid cancer is diagnosed is to obtain a comprehensive, high-resolution ultrasound. This is important because papillary thyroid cancer and other types of thyroid cancer commonly spread to lymph nodes in the neck. If these are positive for thyroid cancer, fortunately, the surgeon will do a comprehensive surgery to remove both the thyroid and the lymph nodes.

What is the prognosis of thyroid cancer?

Fortunately, the prognosis for most patients with thyroid cancer is excellent. This means that the thyroid cancer is not life-threatening and very treatable. In a small group of patients, the disease may be advanced. With greater science, with data from the laboratory and clinical trials, and with technology, we're able to improve the treatments for our patients. And these patients have improved outcomes and better prognosis.

Will my thyroid function be impacted by cancer?

Fortunately, for small thyroid cancers, it does not impact the function of the gland. We measure the function of the gland by measuring hormones called TSH and T4. And if these are normal, it means the thyroid function has been preserved.

Is it possible to save part of my thyroid?

If you've been diagnosed with papillary thyroid cancer, you may be able to save part of your thyroid. We know that most papillary thyroid cancers - under 3 to 4 centimeters - that are confined to the thyroid are low risk. This means that patients can undergo lobectomy to remove half the gland instead of the entire gland. The benefit of this is that you might be able to preserve your own thyroid function after surgery.

What side effects can I expect after surgery?

Many patients are concerned about their quality of life and function after removing the thyroid gland. Fortunately, we have a hormone called levothyroxine or Synthroid. This hormone is bioidentical to the hormone your thyroid produced. It's safe. It's effective. And there's no side effects when you're on the right dose.

How can I be the best partner to my medical team?

The best way to partner with your team is to be open with your team about your questions, your fears and anxieties about your disease, and to be honest about your goals of care. Often writing your questions down and listing your priorities can be very helpful with you and your team determining what's the best next step for you. Never hesitate to ask your medical team any questions or concerns you have. Being informed makes all the difference. Thanks for your time and we wish you well.

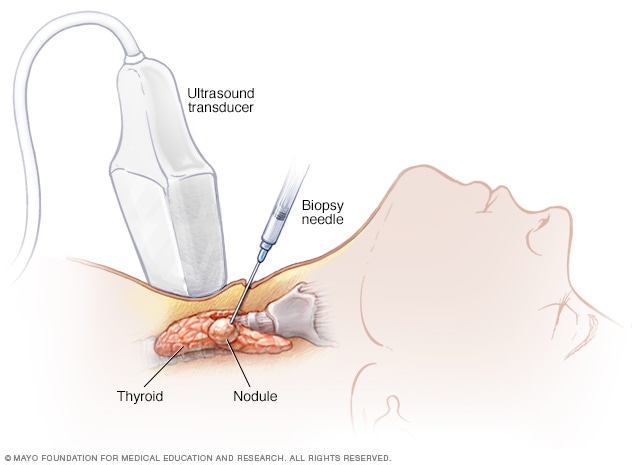

Needle biopsy

Needle biopsy

During needle biopsy, a long, thin needle is inserted through the skin and into the suspicious area. Cells are removed and tested to look for signs of cancer.

Tests and procedures used to diagnose thyroid cancer include:

- Physical exam. Your health care provider will examine your neck to feel for changes in your thyroid, such as a lump (nodule) in the thyroid. The provider may also ask about your risk factors, such as past exposure to radiation and a family history of thyroid cancers.

- Thyroid function blood tests. Tests that measure blood levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and hormones produced by your thyroid gland might give your health care team clues about the health of your thyroid.

-

Ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to create pictures of body structures. To create an image of the thyroid, the ultrasound transducer is placed on your lower neck.

The way a thyroid nodule looks on an ultrasound image helps your provider determine if it's likely to be cancer. Signs that a thyroid nodule is more likely to be cancerous include calcium deposits (microcalcifications) within the nodule and an irregular border around the nodule. If there's a high likelihood that a nodule might be cancerous, additional tests are needed to confirm the diagnosis and determine what type of thyroid cancer is present.

Your provider may also use ultrasound to create images of the lymph nodes in the neck (lymph node mapping) to look for signs of cancer.

-

Removing a sample of thyroid tissue. During a fine-needle aspiration biopsy, your provider inserts a long, thin needle through your skin and into the thyroid nodule. Ultrasound imaging is typically used to precisely guide the needle. Your provider uses the needle to remove some cells from the thyroid. The sample is sent to a lab for analysis.

In the lab, a doctor who specializes in analyzing blood and body tissue (pathologist) examines the tissue sample under a microscope and determines whether cancer is present. The results aren't always clear. Some types of thyroid cancer, particularly follicular thyroid cancer and Hurthle cell thyroid cancer, are more likely to have uncertain results (indeterminate thyroid nodules). Your provider may recommend another biopsy procedure or an operation to remove the thyroid nodule for testing. Specialized tests of the cells to look for gene changes (molecular marker testing) also can be helpful.

-

An imaging test that uses a radioactive tracer. A radioactive iodine scan uses a radioactive form of iodine and a special camera to detect thyroid cancer cells in your body. It's most often used after surgery to find any cancer cells that might remain. This test is most helpful for papillary and follicular thyroid cancers.

Healthy thyroid cells absorb and use iodine from the blood. Some types of thyroid cancer cells do this, too. When the radioactive iodine is injected in a vein or swallowed, any thyroid cancer cells in the body will take up the iodine. Any cells that take up the iodine are shown on the radioactive iodine scan images.

- Other imaging tests. You may have one or more imaging tests to help your provider determine whether your cancer has spread beyond the thyroid. Imaging tests may include ultrasound, CT and MRI.

- Genetic testing. A portion of medullary thyroid cancers are caused by inherited genes that are passed from parents to children. If you're diagnosed with medullary thyroid cancer, your provider may recommend meeting with a genetic counselor to consider genetic testing. Knowing that you have an inherited gene can help you understand your risk of other types of cancer and what your inherited gene may mean for your children.

Thyroid cancer staging

Your health care team uses information from your tests and procedures to determine the extent of the cancer and assign it a stage. Your cancer's stage tells your care team about your prognosis and helps them select the treatment that's most likely to help you.

Cancer stage is indicated with a number between 1 and 4. A lower number usually means the cancer is likely to respond to treatment, and it often means the cancer only involves the thyroid. A higher number means the diagnosis is more serious, and the cancer may have spread beyond the thyroid to other parts of the body.

Different types of thyroid cancer have different sets of stages. For instance, medullary and anaplastic thyroid cancers each have their own set of stages. Differentiated thyroid cancer types, including papillary, follicular, Hurthle cell and poorly differentiated, share a set of stages. For differentiated thyroid cancers, your stage may vary based on your age.

Treatment

Your thyroid cancer treatment options depend on the type and stage of your thyroid cancer, your overall health, and your preferences.

Most people diagnosed with thyroid cancer have an excellent prognosis, as most thyroid cancers can be cured with treatment.

Treatment may not be needed right away

Treatment might not be needed right away for very small papillary thyroid cancers (papillary microcarcinomas) because these cancers have a low risk of growing or spreading. As an alternative to surgery or other treatments, you might consider active surveillance with frequent monitoring of the cancer. Your health care provider might recommend blood tests and an ultrasound exam of your neck once or twice a year.

In some people, the cancer might never grow and never require treatment. In others, growth may eventually be detected and treatment can begin.

Surgery

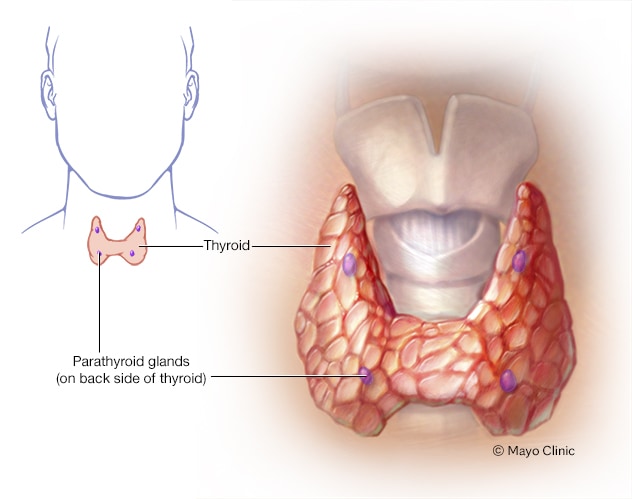

Parathyroid glands

Parathyroid glands

The four tiny parathyroid glands, which lie near the thyroid, make the parathyroid hormone. The hormone plays a role in controlling levels of the minerals calcium and phosphorus in the body.

Most people with thyroid cancer that requires treatment will undergo surgery to remove part or all of the thyroid. Which operation your health care team might recommend depends on your type of thyroid cancer, the size of the cancer and whether the cancer has spread beyond the thyroid to the lymph nodes. Your care team also considers your preferences when creating a treatment plan.

Operations used to treat thyroid cancer include:

- Removing all or most of the thyroid (thyroidectomy). An operation to remove the thyroid gland might involve removing all of the thyroid tissue (total thyroidectomy) or most of the thyroid tissue (near-total thyroidectomy). The surgeon often leaves small rims of thyroid tissue around the parathyroid glands to reduce the risk of damage to the parathyroid glands, which help regulate the calcium levels in your blood.

- Removing a portion of the thyroid (thyroid lobectomy). During a thyroid lobectomy, the surgeon removes half of the thyroid. Lobectomy might be recommended if you have a slow-growing thyroid cancer in one part of the thyroid, no suspicious nodules in other areas of the thyroid and no signs of cancer in the lymph nodes.

- Removing lymph nodes in the neck (lymph node dissection). Thyroid cancer often spreads to nearby lymph nodes in the neck. An ultrasound examination of the neck before surgery may reveal signs that cancer cells have spread to the lymph nodes. If so, the surgeon may remove some of the lymph nodes in the neck for testing.

To access the thyroid, surgeons usually make a cut (incision) in the lower part of the neck. The size of the incision depends on your situation, such as the type of operation and the size of your thyroid gland. Surgeons usually try to place the incision in a skin fold where it will be difficult to see as it heals and becomes a scar.

Thyroid surgery carries a risk of bleeding and infection. Damage to your parathyroid glands also can occur during surgery, which can lead to low calcium levels in your body.

There's also a risk that the nerves connected to your vocal cords might not work as expected after surgery, which can cause hoarseness and voice changes. Treatment can improve or reverse nerve problems.

After surgery, you can expect some pain as your body heals. How long it takes to recover will depend on your situation and the type of surgery you had. Most people start to feel recovered in 10 to 14 days. Some restrictions on your activity might continue. For instance, your surgeon might recommend staying away from strenuous activity for a few more weeks.

After surgery to remove all or most of the thyroid, you might have blood tests to see if all of the thyroid cancer has been removed. Tests might measure:

- Thyroglobulin — a protein made by healthy thyroid cells and differentiated thyroid cancer cells

- Calcitonin — a hormone made by medullary thyroid cancer cells

- Carcinoembryonic antigen — a chemical produced by medullary thyroid cancer cells

These blood tests are also used to look for signs of cancer recurrence.

Thyroid hormone therapy

Thyroid hormone therapy is a treatment to replace or supplement the hormones produced in the thyroid. Thyroid hormone therapy medication is usually taken in pill form. It can be used to:

-

Replace thyroid hormones after surgery. If your thyroid is removed completely, you'll need to take thyroid hormones for the rest of your life to replace the hormones your thyroid made before your operation. This treatment replaces your natural hormones, so there shouldn't be any side effects once your health care team finds the dose that's right for you.

You might also need thyroid hormone replacement after having surgery to remove part of the thyroid, but not everyone does. If your thyroid hormones are too low after surgery (hypothyroidism), your health care team might recommend thyroid hormones.

- Suppress the growth of thyroid cancer cells. Higher doses of thyroid hormone therapy can suppress the production of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) from your brain's pituitary gland. TSH can cause thyroid cancer cells to grow. High doses of thyroid hormone therapy might be recommended for aggressive thyroid cancers.

Radioactive iodine

Radioactive iodine treatment uses a form of iodine that's radioactive to kill thyroid cells and thyroid cancer cells that might remain after surgery. It's most often used to treat differentiated thyroid cancers that have a risk of spreading to other parts of the body.

You might have a test to see if your cancer is likely to be helped by radioactive iodine, since not all types of thyroid cancer respond to this treatment. Differentiated thyroid cancer types, including papillary, follicular and Hurthle cell, are more likely to respond. Anaplastic and medullary thyroid cancers usually aren't treated with radioactive iodine.

Radioactive iodine treatment comes as a capsule or liquid that you swallow. The radioactive iodine is taken up primarily by thyroid cells and thyroid cancer cells, so there's a low risk of harming other cells in your body.

Which side effects you experience will depend on the dose of radioactive iodine you receive. Higher doses may cause:

- Dry mouth

- Mouth pain

- Eye inflammation

- Altered sense of taste or smell

Most of the radioactive iodine leaves your body in your urine in the first few days after treatment. You'll be given instructions for precautions you need to take during that time to protect other people from the radiation. For instance, you may be asked to temporarily avoid close contact with other people, especially children and pregnant women.

Injecting alcohol into cancers

Alcohol ablation, which is also called ethanol ablation, involves using a needle to inject alcohol into small areas of thyroid cancer. Ultrasound imaging is used to precisely guide the needle. The alcohol causes the thyroid cancer cells to shrink.

Alcohol ablation may be an option to treat small areas of thyroid cancer, such as cancer that's found in a lymph node after surgery. Sometimes it's an option if you aren't healthy enough for surgery.

Treatments for advanced thyroid cancers

Aggressive thyroid cancers that grow more quickly may require additional treatment options to control the disease. Options might include:

-

Targeted drug therapy. Targeted drug treatments focus on specific chemicals present within cancer cells. By blocking these chemicals, targeted drug treatments can cause cancer cells to die. Some of these treatments come in pill form and some are given through a vein.

There are many different targeted therapy drugs for thyroid cancer. Some target the blood vessels that cancer cells make to bring nutrients that help the cells survive. Other drugs target specific gene changes. Your provider may recommend special tests of your cancer cells to see which treatments might help. Side effects will depend on the specific drug you take.

- Radiation therapy. External beam radiation uses a machine that aims high-energy beams, such as X-rays and protons, to precise points on your body to kill cancer cells. Radiation therapy might be recommended if your cancer doesn't respond to other treatments or if it comes back. Radiation therapy can help control pain caused by cancer that spreads to the bones. Radiation therapy side effects depend on where the radiation is aimed. If it's aimed at the neck, side effects might include a sunburn-like reaction on the skin, a cough and painful swallowing.

- Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy is a drug treatment that uses chemicals to kill cancer cells. There are many different chemotherapy drugs that can be used alone or in combination. Some come in pill form, but most are given through a vein. Chemotherapy may help control fast-growing thyroid cancers, such as anaplastic thyroid cancer. In certain situations, chemotherapy might be used for other types of thyroid cancer. Sometimes chemotherapy is combined with radiation therapy. Chemotherapy side effects depend on the specific drugs you receive.

- Destroying cancer cells with heat and cold. Thyroid cancer cells that spread to the lungs, liver and bones can be treated with heat and cold to kill the cancer cells. Radiofrequency ablation uses electrical energy to heat up cancer cells, causing them to die. Cryoablation uses a gas to freeze and kill cancer cells. These treatments can help control small areas of cancer cells.

Supportive (palliative) care

Palliative care is specialized medical care that focuses on providing relief from pain and other symptoms of a serious illness. Palliative care specialists work with you, your family and your health care team to provide an extra layer of support that complements your ongoing care.

Palliative care can be used while undergoing other aggressive treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Increasingly, palliative care is being offered early in the course of cancer treatment.

When palliative care is used along with all of the other appropriate treatments, people with cancer may feel better, have a better quality of life and live longer.

Palliative care is provided by a team of doctors, nurses and other specially trained professionals. Palliative care teams aim to improve quality of life for people with cancer and their families.

Follow-up tests for thyroid cancer survivors

After your thyroid cancer treatment ends, your provider may recommend follow-up tests and procedures to look for signs that your cancer has returned. You may have follow-up appointments once or twice a year for several years after treatment ends.

Which tests you need will depend on your situation. Follow-up tests may include:

- Physical exam of your neck

- Blood tests

- Ultrasound exam of your neck

- Other imaging tests, such as CT and MRI

More Information

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Coping and support

It can take time to accept and learn to cope with a thyroid cancer diagnosis. Everyone eventually finds their own way of coping. Until you find what works for you, consider trying to:

- Find out enough about thyroid cancer to make decisions about your care. Write down the details of your thyroid cancer, such as the type, stage and treatment options. Ask your health care provider where you can go for more information. Good sources of information to get you started include the National Cancer Institute, the American Cancer Society and the American Thyroid Association.

- Connect with other thyroid cancer survivors. You might find comfort in talking with people in your same situation. Ask your provider about support groups in your area. Or connect with thyroid cancer survivors online through the American Cancer Society Cancer Survivors Network or the Thyroid Cancer Survivors' Association.

- Control what you can about your health. You can't control whether or not you develop thyroid cancer, but you can take steps to keep your body healthy during and after treatment. For instance, eat a healthy diet full of a variety of fruits and vegetables. Get enough sleep each night so that you wake feeling rested. Try to incorporate physical activity into most days of your week. And find ways to cope with stress.

Preparing for your appointment

If you have signs and symptoms that worry you, start by seeing your family health care provider. If your provider suspects that you may have a thyroid problem, you may be referred to a doctor who specializes in diseases of the endocrine system (endocrinologist).

Because appointments can be brief, and because there's often a lot of information to discuss, it's a good idea to be prepared. Here's some information to help you get ready, and what to expect.

What you can do

- Be aware of any pre-appointment restrictions. At the time you make the appointment, be sure to ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as restrict your diet.

- Write down any symptoms you're experiencing, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment.

- Write down key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medications, vitamins or supplements that you're taking. Remember to include any medicines you take that are available without a prescription.

- Take a family member or friend along. Sometimes it can be difficult to recall all the information provided during an appointment. Someone who accompanies you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

- Write down questions to ask your provider. Write down your top three concerns so that you can be sure to discuss those before moving on to other concerns.

Your time with your provider is limited, so preparing a list of questions can help you make the most of your time together. List your questions from most important to least important in case time runs out. For thyroid cancer, some basic questions to ask include:

- What type of thyroid cancer do I have?

- What stage is my thyroid cancer?

- What treatments do you recommend?

- What are the benefits and risks of each treatment option?

- I have other health problems. How can I best manage them together?

- Will I be able to work and do my usual activities during thyroid cancer treatment?

- Should I seek a second opinion?

- Should I see a doctor who specializes in thyroid diseases?

- How quickly do I need to make a decision about thyroid cancer treatment? Can I take some time to consider my options?

- What might happen if I decide to have regular checkups but not have cancer treatment?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can take with me? What websites do you recommend?

- Am I able to access my medical records through an online patient portal?

If any additional questions occur to you during your visit, don't hesitate to ask.

What to expect from your doctor

Your provider is likely to ask you a number of questions. Being ready to answer them may reserve time to go over points you want to talk about in-depth. Your provider may ask:

- When did you first begin having symptoms?

- Are your symptoms occasional or continuous?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- Does anything seem to improve your symptoms?

- Does anything seem to make your symptoms worse?

- Have you ever been treated with radiation therapy?

- Have you ever been exposed to fallout from a nuclear accident?

- Does anyone in your family have a history of goiter or thyroid or other endocrine cancers?

- Have you been diagnosed with any other medical conditions?

- What medications are you currently taking, including vitamins and supplements?

- What have other health care providers shared with you about your condition?

Dec. 23, 2025