Overview

How cochlear implants work

How cochlear implants work

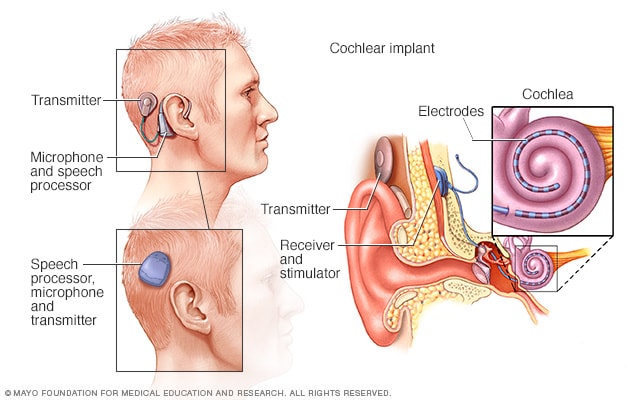

A cochlear implant uses a sound processor that's worn behind the ear. The processor takes sounds from outside the ear. It sends the sound signals to a receiver that's been put under the skin behind the ear. The receiver sends the signals to electrodes that have been put in the snail-shaped inner ear, called the cochlea. The signals activate the cochlear nerve, which sends the signals to the brain. The brain hears those signals as sounds. There are two styles of cochlear implant external processors. One type is a single unit worn off the ear that has a speech processor, microphone, magnet and transmitter in it (lower left). Another is the over-the-ear processor. The parts are in two pieces that are connected by a wire (upper left).

A cochlear implant is an electronic device that improves hearing. It can be a choice for people who have severe hearing loss from inner-ear damage and can't hear well with hearing aids.

A cochlear implant sends sounds past the damaged part of the ear straight to the hearing nerve, called the cochlear nerve. For most people with hearing loss that involves the inner ear, the cochlear nerve works. But the nerve endings, called hair cells, in the part of the inner ear called the cochlea, are damaged.

Cochlear implants use a sound processor that fits behind the ear and pulls in sounds from outside the ear. It sends sound signals to a receiver that's been placed under the skin behind the ear.

The receiver sends the sound signals down an attached thin wire. The wire holds tiny sound electrodes that have been placed in the snail-shaped inner ear, called the cochlea.

The signals trigger the cochlear nerve. The nerve sends the signals to the brain. The brain hears those signals as sounds. These sounds are like natural hearing, but not quite the same.

It takes time and training to learn to hear the signals from a cochlear implant as words. Within 3 to 6 months of use, most people with cochlear implants make big gains in understanding speech.

Mayo Clinic Minute: The road to hearing for baby Aida

Vivien Williams: The happy sounds of childhood, a brother's giggle, a mother's loving coo or the joy of your own calls of contentment.

Matt Little: Very happy.

Melinda Little: She loves her daddy.

Vivien Williams: Baby Aida can't hear any of it. She was born deaf.

Melinda Little: When you first hear it, you kind of say, "That's not true,' or, 'What can we do to help it?"

Vivien Williams: Aida's mom and dad, Melinda and Matt Little, took her to Mayo Clinic, where a team of experts diagnosed Aida with a rare genetic condition.

Lisa Schimmenti, M.D.: Aida has a condition called Waardenburg syndrome.

Vivien Williams: Geneticist Dr. Lisa Schimmenti says Waardenburg syndrome is a collection of symptoms caused by a change in a gene.

Dr. Schimmenti: If you went and Googled this disorder, you'll see pictures of people who may have a white streak of hair, or they may have one blue eye and one brown eye…well, this the fish lab.

Vivien Williams: Some of the tools Dr. Schimmenti uses to learn about deafness similar to Aida's are tanks full of zebra fish.

Dr. Schimmenti: We share 70 percent of our genome with zebrafish, and the same genes that cause conditions in us, cause the same condition in fish.

Vivien Williams: But, unlike these fish, Aida may benefit from technology to help her hear.

Matthew Carlson, M.D.: Cochlear implant surgery and cochlear implant technology has evolved very significantly over the last several decades.

Vivien Williams: Surgeon Dr. Matthew Carlson is also on Aida's care team.

Dr. Carlson: There's a lot of different changes that happen in the inner ear that result in this hearing loss, but the end result is loss of inner ear hair cells for almost all these different conditions.

Vivien Williams: Here are the basics on how hearing works. The outer ear collects sound, which travels down the ear canal to the ear drum. The soundwaves cause the ear drum and middle ear bones to vibrate. The sound waves then move into the inner ear, or cochlea, where tiny hair cells turn them into electrical signals that are transmitted to the brain. A cochlear implant bypasses the missing hair cells. Baby Aida, like all patients who get cochlear implants, went through two steps. First was surgery. Through a small incision, Dr. Carlson and his team...

Dr. Carlson: …slip a small group of electrodes or wires that are all kind of bundled together, and they follow the natural curvature of the cochlea. And the electrodes are connected to a device that's underneath the skin in the scalp.

Vivien Williams: The device sends a tiny current via the electrodes to the cochlea and then to the brain.

Matt Little: ...to activate it, they'll just have the outer piece attached, and then it's just like, basically, from what I understand, like a Bluetooth headset, pretty much.

Vivien Williams: Cochlear implants work for most people who have them, but there's always the chance they won't. Aida's brother, parents, grandparents and cousins were all there the day audiologists at Mayo Clinic attached the outside piece behind Aida's ear and turned it on for the first time.

Matt Little: "Hi, beautiful. Can you hear me? It's Daddy."

Matt and Melinda Little: "Hi …Hi, Aida. Hi, Aida. Hi, big girl. Hello. Hi."

Vivien Williams: To people in that room, witnessing Aida hear for the first time was to witness a miracle.

Melissa DeJong, Au.D.: For me, it's what brings me to work every day.

Matt Little: Just to be able to hear, — hear the sounds around her — that's what I'm looking forward to.

Vivien Williams: For Aida to be able to hear the happy sounds of childhood. For the Mayo Clinic News Network, I'm Vivien Williams.

Mayo Clinic Minute: New technology for cochlear implants

Vivien Williams: If hearing aids don't work for you, cochlear implants might. New technology is helping to make cochlear implants even better.

Colin Driscoll, M.D., Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, Mayo Clinic: "One of the more exciting things that's been developed in the last number of years is surrounding the concept of preserving the hearing that people currently have."

Vivien Williams: Dr. Colin Driscoll says some people who choose cochlear implants do have some level of hearing. It's just not good.

Before the new technology was available, any residual hearing that did exist was lost during surgery to implant the device.

Colin Driscoll, M.D.: "The idea now is, can we preserve that functional, mildly useful hearing and then augment it with the cochlear implant?"

Vivien Williams: The new technology allows Dr. Driscoll and his team to monitor hearing levels during surgery to make sure implantation does not disrupt existing hearing. It allows patients to…

Colin Driscoll, M.D.: "... get the best of both worlds. Hang on to what you have and then augment what you don't have."

Vivien Williams: For the Mayo Clinic News Network, I'm Vivien Williams.

Products & Services

Why it's done

Cochlear implants can improve hearing in people with severe hearing loss when hearing aids no longer help. Cochlear implants can help them talk and listen and improve the quality of their lives.

Cochlear implants may be put in one ear, called unilateral. Some people have cochlear implants in both ears, called bilateral.

Adults often have one cochlear implant and one hearing aid at first. Adults may then move to two cochlear implants as the hearing loss gets worse in the ear with the hearing aid. Some people who have bad hearing in both ears get cochlear implants in both ears at the same time.

Cochlear implants often are put in both ears at the same time in children who have severe hearing loss in both ears. This is most often done for infants and children who are learning to speak.

People who have cochlear implants say the following improve

- Hearing speech without cues such as lip reading.

- Hearing everyday sounds and knowing what they are, including sounds that are warnings of danger.

- Being able to listen in noisy places.

- Knowing where sounds are coming from.

- Hearing television programs and being able to talk on the telephone.

Some people say that the ringing or buzzing in the ear, called tinnitus, improves in the ear with the implant.

To get a cochlear implant, you must:

- Have hearing loss that gets in the way of talking with others.

- Not get much help from hearing aids, as shown by hearing tests.

- Be willing to learn how to use the implant and be part of the hearing world.

- Accept what cochlear implants can and can't do for hearing.

Risks

Cochlear implant surgery is safe. But rare risks can include:

- Infection of the membranes around the brain and spinal cord, called bacterial meningitis. Vaccinations to cut the risk of meningitis most often are given before the surgery.

- Bleeding.

- Being unable to move the face on the side of surgery, called facial paralysis.

- Infection at the surgery site.

- Device infection.

- Balance problems.

- Dizziness.

- Taste problems.

- New or worse ringing or buzzing in the ear, called tinnitus.

- Brain fluid leak, also called cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF).

- Long-term pain, numbness or headache at the site of the implant.

- Not hearing better with the cochlear implant.

Other issues that can happen with a cochlear implant include:

- Loss of what's left of the natural hearing in the ear with the implant. It's common to lose what's left of the hearing in the ear with the implant. This loss doesn't much affect how well you hear with the cochlear implant.

- Failure of device. Rarely, surgery may be needed to replace a cochlear implant that is broken or not working well.

How you prepare

Before cochlear implant surgery, your surgeon will give you details to help you prepare. They may include:

- Which medicines or supplements you need to stop taking and for how long.

- When to stop eating and drinking.

What you can expect

Before the procedure

Before getting cochlear implants, you'll likely have:

- Tests of hearing, speech and maybe balance.

- A physical exam.

- MRI or CT scans of the ears and head to check the cochlea and inner ear.

You'll work with a health care professional trained in hearing loss, called an audiologist, and an ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeon to find which cochlear implant type is best for you. All cochlear implants include both inner, called internal, and outer, called external, parts. Choices include:

- An internal cochlear implant with an external unit that goes behind the ear on the side of the head. The external unit has a speech processor, microphone, magnet and transmitter in a single device. It can be charged when needed.

- An internal cochlear implant with an external sound processor that fits over the ear and a magnet and transmitter that is behind the ear. This processor has two small parts that are connected by a thin cable wire.

External unit of cochlear implant and charger

External unit of cochlear implant and charger

One type of cochlear implant external processor is an outer unit that goes on the side of the head behind the ear. The unit has a speech processor, microphone, magnet and transmitter. It can be charged when needed. It also can use batteries that can be replaced.

Over-the-ear external unit (processor) of a cochlear implant

Over-the-ear external unit (processor) of a cochlear implant

For one type of cochlear implant external processor, the outside piece fits over the ear. The transmitter goes on the side of the head behind the ear. It connects to the over-the-ear part with a small wire.

Researchers are looking at making a totally implantable system. All the parts of the cochlear implant would be under the skin where they can't be seen.

During the procedure

Cochlear implant surgery is most often done with medicine, called general anesthesia, that causes a sleep-like state. With general anesthesia you feel no pain and aren't aware of the surgery.

Your surgeon will make a small cut behind your ear. Then the surgeon makes a small hole in the part of skull bone, called the mastoid, where the internal device rests.

Your surgeon then makes a small opening in the cochlea. They do this in order to thread in the electrode of the internal device. They stitch the skin closed so that the internal device is under the skin.

After the procedure

For a short time, you or your child might have:

- Pressure or discomfort over the ear that has the device.

- Dizziness or nausea.

Most people can go home the day of surgery. If you're an adult, you will need someone to drive you home. You can't drive the same day you have anesthesia. Expect to go back to see a member or your cochlear implant team in the first few weeks to check on healing.

Turning on the device

About 1 to 4 weeks after surgery, an audiologist turns on the device. Sometimes it can be as early as the day after surgery. The audiologist:

- Adjusts the sound processor to fit.

- Checks the parts of the cochlear implant to make sure they work.

- Finds out what sounds you or your child hears.

- Tells you how to care for and use the device.

- Sets the device so that you can hear your best.

Rehabilitation

This involves training your brain to understand the sounds you hear through the cochlear implant. At first speech and everyday noises around you won't sound the same as you might recall them.

Your brain needs time to understand the new sounds and to understand speech. This process is ongoing. It's best to wear the speech processor anytime you're awake. You do have to take it off while swimming or showering.

Regular, often lifelong, follow-up visits will help you get the most from your cochlear implants. Follow-up visits include checking your hearing, programming the device and doing other testing.

Results

The results of cochlear implant surgery vary from person to person. The cause of your hearing loss can affect how well cochlear implants work for you. So can how long you've had severe hearing loss and if you learned to talk or read before hearing loss.

Cochlear implants most often work better in people who knew how to speak and read before the hearing loss. Children born with severe hearing loss often get the best results from getting a cochlear implant at a young age. Then they can hear better while learning speech and language.

For adults, the best results often are linked to less time between hearing loss and cochlear implant surgery. Adults who have heard little or no sound since birth tend to get less help from cochlear implants. Even so, for most of these adults, hearing improves some after getting cochlear implants.

Outcomes might include:

- Clearer hearing. With time, many people get clearer hearing from using the device.

- Improved tinnitus. For now, ear noise, also called tinnitus, isn't a main reason to get a cochlear implant. But a cochlear implant might improve tinnitus during use. Rarely, having an implant can make tinnitus worse.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.