Overview

Cesarean birth is the delivery of a baby through surgical incisions made in the belly and uterus. It often is called a C-section.

A C-section may be planned if there are pregnancy complications. And people who have had a C-section before are more likely to need another one. But the decision for a first-time C-section typically isn't made until after labor starts.

If you're pregnant, knowing what to expect during and after a C-section can help you prepare.

Products & Services

Why it's done

Healthcare professionals may recommend a C-section if:

- Labor slows or stops. Sometimes labor doesn't progress as expected. This condition, called dystocia, is one of the most common reasons for a C-section. It also is called prolonged labor. Labor may be considered prolonged when it takes longer than expected for the cervix to dilate and open. Or it may be considered prolonged when pushing after the cervix is fully dilated doesn't move the baby down in the vagina.

- The baby's heart is not tolerating labor. Concern about changes in a baby's heartbeat may make a C-section the safest option.

- The baby is in an unusual position. A C-section is the safest way to deliver babies whose feet or buttocks enter the birth canal first. This is called a breech birth. A C-section also is safest for babies whose sides or shoulders come first. This is called a transverse birth.

- You're carrying more than one baby. A C-section may be needed if you're carrying twins, triplets or more. This is especially true if labor starts too early or the babies are not in a head-down position.

- There's a problem with the placenta. If the placenta covers the opening of the cervix, the baby can't pass through it. A C-section is then needed for delivery. This condition is called placenta previa.

- There's a prolapsed umbilical cord. If a loop of umbilical cord slips through the cervix before the baby does, a C-section may be needed.

- You have a health concern. A C-section might be recommended if you have certain health issues, such as a heart condition or a brain condition.

- There's a blockage. A large fibroid blocking the birth canal or a pelvic fracture may be reasons for a C-section. Or a baby who has a condition that can cause the head to be unusually large, called severe hydrocephalus, may require a C-section.

- You've had a C-section before or other surgery on the uterus. Although it's often possible to have a vaginal birth after a C-section, your healthcare professional may recommend a repeat C-section. A C-section may be the only option for some people, depending on their past surgeries.

Some people ask for C-sections with their first babies. They may want to avoid labor or the possible complications of vaginal birth. Or they might want to plan the time of delivery. However, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, this may not be a good option. This is especially true if you plan to have several children. The more C-sections you have, the greater the risk of problems with future pregnancies. The risks of a vaginal birth are lower than those of a C-section.

Risks

Like other types of surgery, C-sections carry risks.

Risks to babies include:

- Breathing problems. Babies born by C-section are more likely to develop a breathing issue that causes them to breathe too fast for a few days after birth. This condition is called transient tachypnea.

- Surgical injury. Although rare, accidental nicks to the baby's skin can occur during surgery.

Risks to mothers include:

- Infection. After a C-section, there is a risk of developing an infection of the lining of the uterus, called endometritis, in the urinary tract or at the site of an incision.

- Blood loss. A C-section has more bleeding during and after delivery.

- Reactions to anesthesia. Reactions to any type of anesthesia are possible.

- Blood clots. A C-section may increase the risk of developing a blood clot inside a deep vein, especially in the legs or pelvis. This is called deep vein thrombosis. If a blood clot travels to the lungs and blocks blood flow, it is called a pulmonary embolism. This can be a life-threatening condition.

- Surgical injury. Although rare, surgical injuries to the bladder or bowel can occur during a C-section.

-

Increased risks during future pregnancies. Having a C-section increases the risk of complications in a later pregnancy. The more C-sections, the higher the risks of scar tissue. Issues with the placenta, such as placenta previa and placenta accreta, also may happen. Placenta accreta happens when the placenta becomes attached to the wall of the uterus.

A C-section also increases the risk of the uterus tearing along the scar line if you decide to try a vaginal delivery in a later pregnancy. This tearing is called uterine rupture. Uterine rupture can be life-threatening for a baby.

How you prepare

For a planned C-section, you may talk with an anesthesiologist. An anesthesiologist is a doctor who specializes in giving medicine to keep you comfortable during surgery. The anesthesiologist talks with you about the risk of complications from anesthesia.

Your healthcare professional may recommend blood tests before a C-section. These tests check your blood type and measure hemoglobin levels. Hemoglobin is the main component of red blood cells. The results ensure a safe blood transfusion if needed during the C-section.

Even for a planned vaginal birth, it's important to prepare for the unexpected. Talk about the possibility of a C-section with your healthcare professional well before your due date.

If you don't plan to have more children, talk to your health professional about long-acting reversible birth control or permanent birth control. You can have a procedure for permanent birth control at the time of the C-section if you chose.

What you can expect

Before the procedure

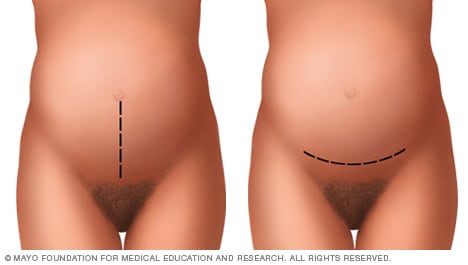

Abdominal incisions used during C-section

Abdominal incisions used during C-section

A C-section includes two surgical cuts, called incisions. The first incision is made through the skin on the abdomen. The cut may run top to bottom, or vertically, between the belly button and pubic hair (shown left). Or the cut may go from side to side, or horizontally, lower down on the abdomen (shown right). The horizontal cut on the lower abdomen is more common during a C-section.

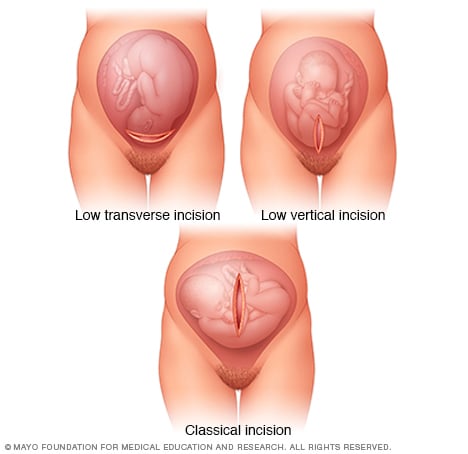

Uterine incisions used during C-section

Uterine incisions used during C-section

A C-section includes two surgical cuts, called incisions. After the first cut through the skin, a cut is made through the wall of the uterus. The images above show how the cut through the uterus might be made. Low transverse incisions, shown at the top left, are the most common.

A C-section can be done in different ways, but most C-sections have these things in common:

- At home. Your healthcare professional may ask you to shower at home with an antiseptic soap the night before and the morning of your C-section. But don't shave your pubic hair within 24 hours of your C-section. This can increase the risk of infection. If needed, a member of your care team will trim your pubic hair before surgery.

- At the hospital. Your abdomen will be cleansed. A thin tube, called a catheter, typically is placed into your bladder to collect urine. An intravenous line, called an IV, is placed in a vein in your hand or arm. The IV provides fluid, medicines and antibiotics to prevent infection.

-

Anesthesia. Most C-sections use regional anesthesia, which numbs only the lower part of your body. You are awake during the procedure. There are two types of reginal anesthesia. A spinal block is a single injection of medicine that relieves pain for hours. An epidural block delivers medicine through a catheter placed in your back. It provides continuous pain relief. An epidural block often is used during labor.

Some C-sections require general anesthesia. With general anesthesia, you won't be awake during the birth.

During the procedure

A C-section requires a cut into the skin of your abdomen, called an abdominal incision. It also requires a cut into the uterus, called a uterine incision.

- Abdominal incision. First, your doctor makes a cut in the skin and the abdominal wall. It's typically a horizontal incision low on the abdomen near the pubic hairline. A vertical incision is less common. It goes from just below the belly button to just above the pubic bone.

- Uterine incision. The uterine incision happens next. Typically, it is a horizontal incision across the lower part of the uterus. It is called a low transverse incision. Other types of uterine incisions may be used depending on the baby's position and whether there are complications, such as placenta previa or very early preterm delivery.

- Delivery. The baby is delivered through the incisions. Members of your care team clear the baby's mouth and nose of fluids. And they clamp and cut the umbilical cord. The placenta is removed from the uterus. The incisions are closed with stitches, also called sutures.

If you have regional anesthesia and your baby is doing well, you may be able to hold your baby shortly after delivery. If you have general anesthesia, you are asleep for the birth. You're able to hold your baby as soon as you are awake.

After the procedure

Typically, you stay in the hospital for 2 to 3 days after a C-section. Your healthcare professional will talk with you about your options for pain relief in the hospital.

Once the anesthesia begins to wear off, you'll be encouraged to drink fluids and walk. This helps prevent constipation and deep vein thrombosis. Your healthcare team checks your incision for signs of infection. The bladder catheter is removed as soon as possible.

You can start breastfeeding as soon as you're ready, even in the delivery room. Your care team makes sure any pain medicines given are safe for your baby when you breastfeed. Ask your nurse or a lactation consultant to teach you how to position yourself and support your baby so that you're comfortable.

When you go home

As you recover from a C-section, discomfort and fatigue are common. To promote healing:

- Take it easy. Rest when possible. Try to keep everything that you and your baby need within easy reach. For the first few weeks, don't lift more than 10 to 15 pounds.

- Use recommended pain relief. To soothe incision soreness, a heating pad may offer relief. Take pain medicines that are safe while breastfeeding. These include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and acetaminophen (Tylenol, others).

- Wait to drive. As you heal, it may take 1 to 2 weeks before you can comfortably apply brakes and twist to check blind spots. And don’t drive if you are taking prescription pain medicine.

Check your C-section incision for signs of infection each day. Contact your healthcare professional if:

- Your incision is swollen or leaking discharge and there's a change in skin color around the incision. This change may be a shade of red, purple or brown depending on your skin color.

- You have a fever.

- You have heavy bleeding.

- You have pain that's getting worse.

If you have severe mood swings, loss of appetite, extreme fatigue or lack of joy after childbirth, you may have postpartum depression. Contact your healthcare professional right away if you think you might be depressed. Contact them if your depression symptoms don't improve. Call your healthcare professional if you have trouble caring for your baby or managing daily tasks. Also call if you have thoughts of harming yourself or your baby. Getting help is important for your well-being and your baby's health.

Follow-up care

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that postpartum care be ongoing. See or talk with your healthcare professional within three weeks after delivery. Within 12 weeks after delivery, see your healthcare professional for a postpartum follow-up visit.

During this appointment your healthcare professional typically asks about your mood and emotional well-being. You may talk about birth control and birth spacing. Your health professional may review information about infant care and feeding. And you may talk about how you're sleeping and issues related to fatigue.

Your health professional may do a physical exam, including a Pap test if it's due. This exam may include a check of your abdomen, vagina, cervix or uterus to make sure you're healing well.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.

Aug. 29, 2025