May 24, 2016

The past 30 years have seen much progress in the diagnosis and treatment of Marfan syndrome and related disorders.

When Victor A. McKusick, M.D., first described Marfan syndrome in 1955, he predicted that these patients with serious ocular, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular problems would eventually be found to have a mutation in a structural connective tissue protein.

In 1991, his prediction was fulfilled when mutations in a component of elastic microfibrils, fibrillin 1 (FBN1), were found to be the cause of Marfan syndrome. Further research showed that apart from its structural role, fibrillin also has a regulatory function through its interaction with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), a signaling protein involved in many connective tissue functions.

Marfan phenotype includes long limbs

Marfan phenotype includes long limbs

Extended arm span in a woman with Marfan syndrome.

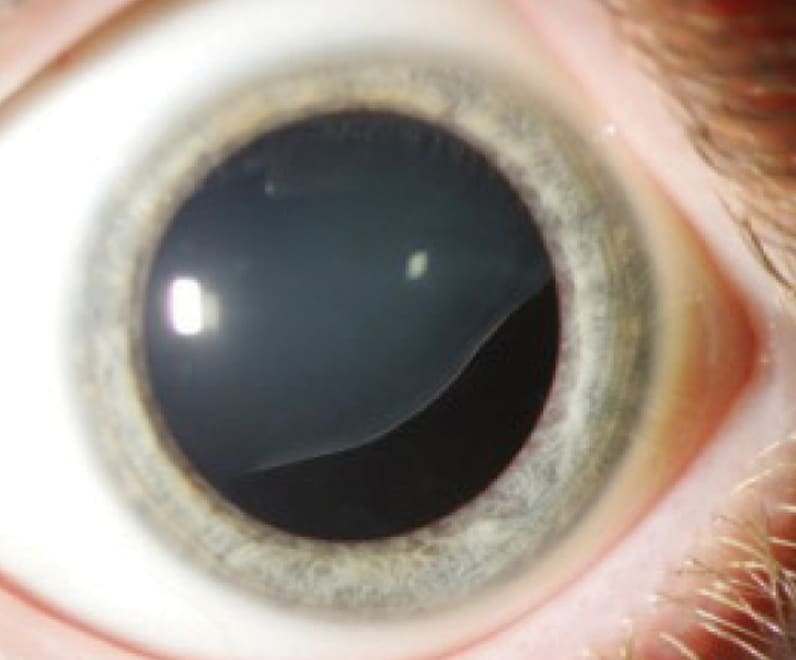

Connective tissue disorder ectopia lentis

Connective tissue disorder ectopia lentis

Ectopia lentis in an individual with Marfan syndrome.

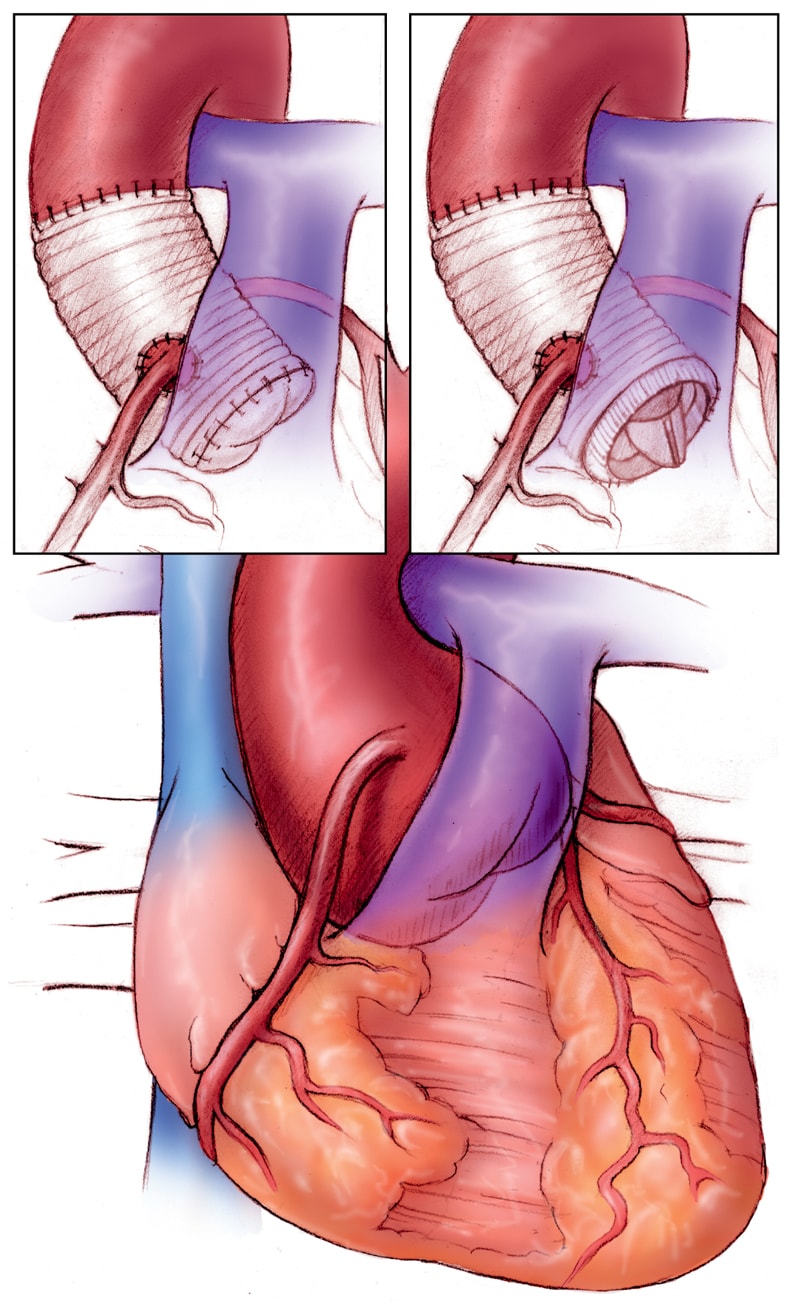

Operative repair of the aortic root

Operative repair of the aortic root

Operative repair of the aortic root in Marfan syndrome. Left, valve-sparing procedure, and right, combined prosthetic valve and root replacement.

Working with the Marfan mouse model, investigators found that FBN1 mutations result in excessive TGF-β signaling. The Marfan phenotype (long limbs, scoliosis, pectus deformity, severe myopia, aortic aneurysm, valvular regurgitation) is the result of disordered TGF-β signaling mediated by the angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor.

Even before the causative mutation was identified, clinical care for patients with Marfan syndrome had advanced. Preventive aortic repair became effective when composite graft repair of the ascending aorta began to be widely used in the 1970s.

β-blockers were shown to slow the rate of aortic enlargement in the 1990s, and clinical care that incorporated medical aortic protection and timely preventive surgery led to a major increase in life expectancy.

The discovery of a signaling pathway malfunction indicated that there was more to Marfan syndrome than structurally weak connective tissue. Investigations using the mouse model demonstrated that when the AT1 receptor was blocked with losartan, young mice with Marfan syndrome did not develop the expected phenotypic changes, including aortic aneurysm.

An early human trial in infants with severe FBN1 mutations confirmed that losartan also reduced the rate of aortic enlargement in humans. Several trials of losartan in young people have confirmed the effectiveness of losartan, although important questions remain and will be addressed in future trials.

Additional mutations causing thoracic aortic aneurysm continue to be identified. Some encode for proteins in the extracellular matrix, others for proteins involved in cellular signaling and others for aortic smooth muscle contractile proteins. Patients often have a marfanoid phenotype, but many have a completely normal appearance with no syndromic features. Genetic testing is often required for an accurate diagnosis.

Diagnosis

The Marfan and Thoracic Aorta Clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, has provided care for patients with Marfan syndrome and related disorders since 2002. Patients are seen at a joint cardiology and medical genetics appointment, where the medical history, family history, clinical examination and imaging results are reviewed. Genetic testing is commonly needed because of overlap in the clinical features between Marfan syndrome and other genetic aortopathies.

Marfan syndrome diagnostic criteria

Negative family history

- The presence of an aortic root aneurysm (with a z score ≥ 2 when standardized to age and body size) or aortic dissection and ectopia lentis

- The presence of an aortic root aneurysm (with a z score ≥ 2 when standardized to age and body size) or aortic dissection and the identification of the FBN1 gene mutation

- The presence of an aortic root aneurysm (with a z score ≥ 2 when standardized to age and body size) or aortic dissection and the presence of systemic features with a score of 7 or more points on the systemic feature scoring table

- The presence of ecopia lentis and identification of the FBN1 gene mutation previously associated with aortic disease

Positive family history

- Ectopia lentis

- Systemic features with a score of 7 or more points

- Aortic root dilation (with a z score ≥ 2 for adults ages 20 or older or a z score ≥ 3 for patients younger than age 20)

Systemic feature scoring table

Feature and value

Wrist and thumb sign — 3

Wrist or thumb sign — 1

Pectus carinatum deformity — 2

Pectus excavatum or chest asymmetry — 1

Hindfoot deformity — 2

Plain flatfoot (pes planus) — 1

Pneumothorax — 2

Dural ectasia —2

Protrusio acetabulae — 2

Reduced upper segment or lower segment (or both) and increased arm span or height (or both) without severe scoliosis — 1

Scoliosis > 20° or thoracolumbar kyphosis — 1

Reduced elbow extension — 1

Three of five facial features — 1

- Dolichocephaly

- Malar hypoplasia

- Enophthalmos

- Retrognathia

- Down-slanting palpebral fissures

Skin striae — 1

Myopia (–0.3 diopter) — 1

Mitral valve prolapse — 1

Total score

Add values. Systemic score ≥ 7 = criteria required for diagnosis

Treatment

When a specific genetic diagnosis is made, the clinical management is guided by that diagnosis. Examples of conditions that appear similar but have specific management are Loeys-Dietz syndrome and vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Marfan syndrome differential diagnosis

Homocystinuria

- MASS phenotype (myopia, mitral valve prolapse, mild aortic enlargement, nonspecific skin and skeletal features)

- Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Stickler syndrome

- Congenital contractural arachnodactyly (Beals syndrome)

- Familial thoracic aortic aneurysm

- Congenital bicuspid aortic valve disease with associated aortopathy

- Loeys-Dietz syndrome

Cases without a definite diagnosis often require multidisciplinary discussion. The care of an individual patient may involve experts in adult and pediatric cardiology, clinical and laboratory genetics, cardiac and vascular imaging, cardiovascular surgery, and cardiovascular pathology.

Patients with Marfan syndrome and related disorders require multidisciplinary care. Physical activity modifications and either a β-blocker or losartan help to protect the aorta. Preventive aortic repair with either a composite graft or a valve-sparing operation is done when the aorta reaches a diameter between 40 and 50 mm.

Earlier preventive surgery is recommended when there is a family history of aortic dissection or when there has been rapid growth of the aorta. Ocular and musculoskeletal problems often need specialty care.

Effective treatment for previously fatal cardiovascular disease has resulted in longer lives for patients with Marfan syndrome. Their care involves lifelong monitoring of cardiovascular health as well as management of noncardiovascular problems. A number of dedicated clinics throughout the United States now help with this care.

Mayo's Marfan and Thoracic Aorta Clinic was selected by The Marfan Foundation to host The Marfan Foundation 32nd Annual Family Conference.

For more information

Learn more about The Marfan Foundation annual conferences.