Diagnosis

An important part of diagnosing Alzheimer's disease includes being able to explain your symptoms. Input from a close family member or friend about your symptoms and their impact on your daily life helps. Tests of memory and thinking skills also help diagnose Alzheimer's disease.

Blood and imaging tests can rule out other potential causes of the symptoms. Or they may help your health care professional better identify the disease causing dementia symptoms.

In the past, Alzheimer's disease was diagnosed for certain only after death when looking at the brain with a microscope revealed plaques and tangles. Health care professional and researchers are now able to diagnose Alzheimer's disease during life with more certainty. Biomarkers can detect the presence of plaques and tangles. Biomarker tests include specific types of PET scans and tests that measure amyloid and tau proteins in the fluid part of blood and cerebral spinal fluid.

Tests

Diagnosing Alzheimer's disease would likely include the following tests:

Physical and neurological exam

A health care professional will perform a physical exam. A neurological exam may include testing:

- Reflexes.

- Muscle tone and strength.

- Ability to get up from a chair and walk across the room.

- Sense of sight and hearing.

- Coordination.

- Balance.

Lab tests

Blood tests may help rule out other potential causes of memory loss and confusion, such as a thyroid disorder or vitamin levels that are too low. Blood tests also can measure levels of beta-amyloid protein and tau protein, but these tests aren't widely available and coverage may be limited.

Mental status and neuropsychological testing

Your health care professional may give you a brief mental status test to assess memory and other thinking skills. Longer forms of this type of test may provide more details about mental function that can be compared with people of a similar age and education level. These tests can help establish a diagnosis and serve as a starting point to track symptoms in the future.

Brain imaging

Brain scan images for diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease

Brain scan images for diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease

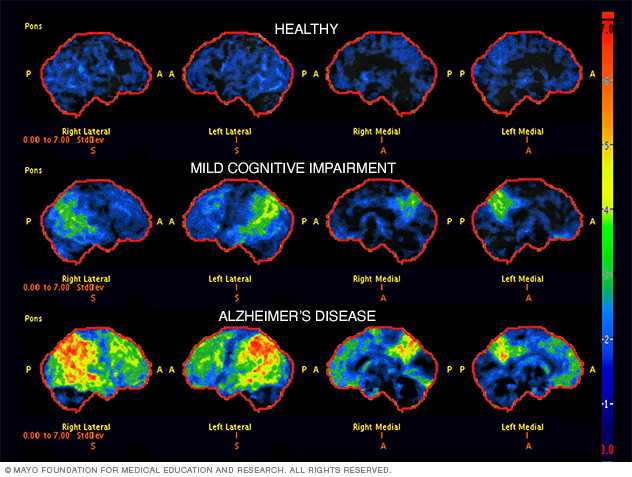

Brain scans (FDG PET) used in the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. The scans show a healthy brain, a brain with mild cognitive impairment and a brain with Alzheimer's disease. Areas that are black and blue represent healthy brain metabolism. Areas that are green, yellow and red represent worsening brain metabolism as the disease progresses.

Images of the brain are typically used to pinpoint visible changes related to conditions other than Alzheimer's disease that may cause similar symptoms, such as strokes, trauma or tumors. New imaging techniques may help detect specific brain changes caused by Alzheimer's, but they're used mainly in major medical centers or in clinical trials.

Imaging of brain structures include:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI uses radio waves and a strong magnetic field to produce detailed images of the brain. While they may show shrinkage of some brain regions associated with Alzheimer's disease, MRI scans also rule out other conditions. An MRI is generally preferred to a CT scan to evaluate dementia.

- Computerized tomography (CT). A CT scan, a specialized X-ray technology, produces cross-sectional images of your brain. It's usually used to rule out tumors, strokes and head injuries.

Positron emission tomography (PET) can capture images of the disease process. During a PET scan, a low-level radioactive tracer is injected into the blood to reveal a particular feature in the brain. PET imaging may include:

- Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET imaging scans show areas of the brain in which nutrients are poorly metabolized. Finding patterns in the areas of low metabolism can help distinguish between Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia.

- Amyloid PET imaging can measure the burden of amyloid deposits in the brain. This test is mainly used in research but may be used if a person has unusual or very early onset of dementia symptoms.

- Tau PET imaging, which measures the tangles in the brain, is generally used in the research setting.

In special circumstances, other tests may be used to measure amyloid and tau in the cerebrospinal fluid. This may be done if symptoms are quickly getting worse or if dementia is affecting someone at a younger age than what's typical.

Future diagnostic tests

Researchers are working to develop tests that can measure biological signs of disease processes in the brain.

These tests, including blood tests, may improve accuracy when making a diagnosis. They also may allow the disease to be diagnosed before symptoms begin. A blood test to measure beta-amyloid levels is currently available.

Genetic testing isn't recommended for most people being evaluated for Alzheimer's disease. But people with a family history of early-onset Alzheimer's disease may consider it. Meet with a genetic counselor to discuss the risks and benefits before getting a genetic test.

More Information

Treatment

Treatments for Alzheimer's disease include medicines that can help with symptoms and newer medicines that can help slow decline in thinking and functioning. These newer medicines are approved for people with early Alzheimer's disease.

Medicines

Alzheimer's medicines can help with memory symptoms and other cognitive changes. Two types of medicines are currently used to treat symptoms:

-

Cholinesterase inhibitors. These medicines work by boosting levels of cell-to-cell communication. The medicines preserve a chemical messenger that is depleted in the brain by Alzheimer's disease. These are usually the first medicines tried, and most people see modest improvements in symptoms.

Cholinesterase inhibitors may improve symptoms related to behavior, such as agitation or depression. The medicines are taken orally or delivered through a patch on the skin. Commonly prescribed cholinesterase inhibitors include donepezil (Aricept, Adlarity), galantamine (Razadyne) and rivastigmine transdermal patch (Exelon).

The main side effects of these drugs include diarrhea, nausea, loss of appetite and sleep disturbances. In people with certain heart disorders, serious side effects may include an irregular heartbeat.

- Memantine (Namenda). This medicine works in another brain cell communication network and slows the progression of symptoms with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. It's sometimes used in combination with a cholinesterase inhibitor. Relatively rare side effects include dizziness and confusion.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved lecanemab (Leqembi) and donanemab (Kisunla) for people with mild Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease.

Clinical trials found that the medicines slowed declines in thinking and functioning in people with early Alzheimer's disease. The medicines prevent amyloid plaques in the brain from clumping.

Lecanemab is given as an IV infusion every two weeks. Side effects of lecanemab include infusion-related reactions such as fever, flu-like symptoms, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, changes in heart rate and shortness of breath.

Donanemab is given as an IV infusion every four weeks. Side effects of the medicine may include flu-like symptoms, nausea, vomiting, headache and changes in blood pressure. Rarely, donanemab can cause a life-threatening allergic reaction and swelling.

Also, people taking lecanemab or donanemab may have swelling in the brain or may get small bleeds in the brain. Rarely, brain swelling can be serious enough to cause seizures and other symptoms. Also in rare instances, bleeding in the brain can cause death. The FDA recommends getting a brain MRI before starting treatment. The FDA also recommends periodic brain MRIs during treatment for symptoms of brain swelling or bleeding.

People who carry a certain form of a gene known as APOE e4 appear to have a higher risk of these serious complications. The FDA recommends testing for this gene before starting treatment.

If you take a blood thinner or have other risk factors for brain bleeding, talk to your healthcare professional before taking lecanemab or donanemab. Blood-thinning medicines may increase the risk of bleeds in the brain.

More research is being done on the potential risks of taking lecanemab and donanemab. Other research is looking at how effective the medicines may be for people at risk of Alzheimer's disease, including people who have a first-degree relative, such as a parent or sibling, with the disease.

Sometimes other medicines such as antidepressants may be prescribed to help control the behavioral symptoms associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Creating a safe and supportive environment

An important part of any treatment plan is to adapt to the needs of a person with Alzheimer's disease. Establish and strengthen routine habits and cut down on tasks that require memory. These steps can make life much easier.

These are ways to support a person's sense of well-being and continued ability to function:

- Keep keys, wallets, mobile phones and other valuables in the same place at home so they don't become lost.

- Keep medicines in a secure location. Use a daily checklist to keep track of doses.

- Arrange for finances to be on automatic payment and automatic deposit.

- Have the person with Alzheimer's carry a mobile phone with location tracking. Program important phone numbers into the phone.

- Install alarm sensors on doors and windows.

- Make sure regular appointments are on the same day at the same time as much as possible.

- Use a calendar or whiteboard to track daily schedules. Build the habit of checking off completed items.

- Remove excess furniture, clutter and throw rugs.

- Install sturdy handrails on stairs and in bathrooms.

- Ensure that shoes and slippers are comfortable and provide good traction.

- Reduce the number of mirrors. People with Alzheimer's may find images in mirrors confusing or scary.

- Make sure that the person with Alzheimer's carries ID or wears a medical alert bracelet.

- Keep photos and other objects with meaning around the house.

More Information

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Alternative medicine

Herbal remedies, vitamins and other supplements are widely promoted for cognitive health or to prevent or delay Alzheimer's. But clinical trials have produced mixed results. There's little evidence to support them as effective treatments.

Some of the treatments that have been studied recently include:

-

Vitamin E. Although vitamin E doesn't prevent Alzheimer's, taking 2,000 international units daily may help delay symptoms getting worse in people who already have mild to moderate disease. However, study results have been mixed, with only some showing modest benefits. Further research into the safety of 2,000 international units daily of vitamin E in a dementia population will be needed before it can be routinely recommended.

Supplements promoted for cognitive health can interact with medicines you're taking for Alzheimer's disease or other health conditions. Work closely with your health care team to create a safe treatment plan. Tell your health care team about your prescriptions and any medicines or supplements you take without a prescription.

- Omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 fatty acids in fish or from supplements may lower the risk of developing dementia. But clinical studies have shown no benefit for treating Alzheimer's disease symptoms.

- Curcumin. This herb comes from turmeric and has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that might affect chemical processes in the brain. So far, clinical trials have found no benefit for treating Alzheimer's disease.

- Ginkgo. Ginkgo is a plant extract. A large study funded by the National Institutes of Health found no effect in preventing or delaying Alzheimer's disease.

- Melatonin. This supplement helps regulate sleep. It's being studied to see if it can help people with dementia manage sleep problems. But some research has indicated that melatonin may worsen mood in some people with dementia. More research is needed.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Healthy lifestyle choices promote good overall health. They also may play a role in maintaining brain health.

Exercise

Regular exercise is an important part of a treatment plan. Activities such as a daily walk can help improve mood and maintain the health of joints, muscles and the heart. Exercise also promotes restful sleep and prevents constipation. It's beneficial for care partners, too.

People with Alzheimer's who have trouble walking may still be able to use a stationary bike, stretch with elastic bands or participate in chair exercises. You may find exercise programs geared to older adults on TV, the internet or DVDs.

Nutrition

People with Alzheimer's may forget to eat, lose interest in meals or may not eat healthy foods. They may also forget to drink enough, leading to dehydration and constipation.

Offer the following:

- Healthy options. Buy favorite healthy food options that are easy to eat.

- Water and other healthy beverages. Encourage drinking several glasses of liquids every day. Avoid beverages with caffeine, which can increase restlessness, interfere with sleep and trigger a need to urinate often.

- High-calorie, healthy shakes and smoothies. Serve milkshakes with protein powders or make smoothies. This is helpful when eating becomes more difficult.

Social engagement and activities

Social activities can support preserved skills and abilities. They also help with over-all well-being. Do things that are meaningful and enjoyable. Someone with dementia might:

- Listen to music or dance.

- Read or listen to books.

- Garden or do crafts.

- Go to social events at senior or memory care centers.

- Do activities with children.

Coping and support

People with Alzheimer's disease experience a mixture of emotions — confusion, frustration, anger, fear, uncertainty, grief and depression.

If you're caring for someone with Alzheimer's, you can help them cope by being there to listen. Reassure the person that life can still be enjoyed, provide support, and do your best to help the person retain dignity and self-respect.

A calm and stable home environment can help reduce behavior problems. New situations, noise, large groups of people, being rushed or pressed to remember, or being asked to do complex tasks can cause anxiety. As a person with Alzheimer's becomes upset, the ability to think clearly declines even more.

Caring for the caregiver

Caring for a person with Alzheimer's disease is physically and emotionally demanding. Feelings of anger, guilt, stress, worry, grief and social isolation are common.

Caregiving can even take a toll on the caregiver's physical health. Pay attention to your own needs and well-being. It's one of the most important things you can do for yourself and for the person with Alzheimer's.

If you're a caregiver for someone with Alzheimer's, you can:

- Learn as much about the disease as you can.

- Ask questions of health care professionals, social workers and others involved in the care of your loved one.

- Call on friends or other family members for help when you need it.

- Take a break every day.

- Spend time with your friends.

- Take care of your health by seeing your own health care professionals on schedule, eating healthy meals and getting exercise.

- Join a support group.

- Make use of a local adult day center, if possible.

Many people with Alzheimer's and their families benefit from counseling or local support services. Contact your local Alzheimer's Association affiliate to connect with support groups, health care professionals, occupational therapists, resources and referrals, home care agencies, residential care facilities, a telephone help line, and educational seminars.

Preparing for your appointment

Medical care for the loss of memory or other thinking skills usually requires a team or partner strategy. If you're worried about memory loss or related symptoms, ask a close relative or friend to go with you to an appointment with a health care professional. In addition to providing support, your partner can provide help in answering questions.

If you're going with someone to a health care appointment, your role may be to provide some history or your thoughts on changes you have seen. This teamwork is an important part of medical care.

Your health care professional may refer you to a neurologist, psychiatrist, neuropsychologist or other specialist for further evaluation.

What you can do

You can prepare for your appointment by writing down as much information as possible to share. Information may include:

- Medical history, including any past or current diagnoses and family medical history.

- Medical team, including the name and contact information of any current physician, mental health professional or therapist.

- Medicines, including prescriptions, medicines you take without a prescription, vitamins, herbs or other supplements.

- Symptoms, including specific examples of changes in memory or thinking skills.

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care professional will likely ask a number of questions to understand changes in memory or other thinking skills. If you are accompanying someone to an appointment, be prepared to provide your thoughts as needed. Your care professional may ask:

- What kinds of memory trouble and mental lapses are you having? When did you first notice them?

- Are they steadily getting worse, or are they sometimes better and sometimes worse?

- Have you stopped doing certain activities, such as managing finances or shopping, because these activities were too mentally challenging?

- How is your mood? Do you feel depressed, sadder or more anxious than usual?

- Have you gotten lost lately while driving or in a situation that's usually familiar to you?

- Has anyone expressed unusual concern about your driving?

- Have you noticed any changes in the way you tend to react to people or events?

- Do you have more energy than usual, less than usual or about the same?

- What medicines are you taking? Are you taking any vitamins or supplements?

- Do you drink alcohol? How much?

- Have you noticed any trembling or trouble walking?

- Are you having trouble remembering health care appointments or when to take your medicines?

- Have you had your hearing and vision tested recently?

- Did anyone else in your family ever have memory trouble? Was anyone ever diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease or dementia?

- Do you act out your dreams while sleeping (punch, flail, shout, scream)? Do you snore?