Feb. 27, 2018

Questionnaire identifies personal and family history of cancer

Questionnaire identifies personal and family history of cancer

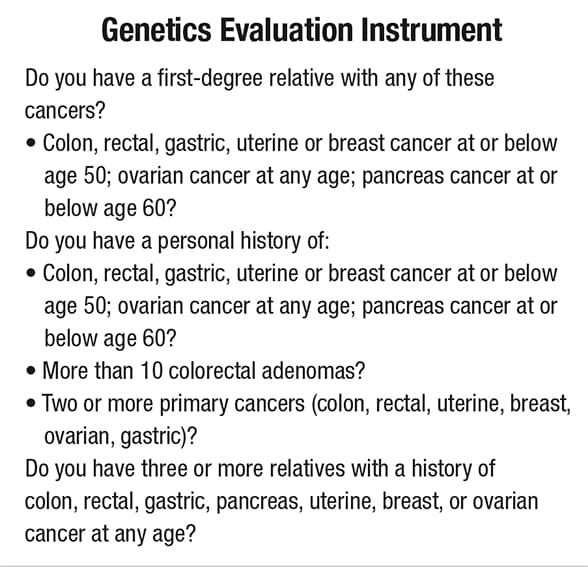

Use of this type of questionnaire in outpatient settings can help improve the identification of high-risk patients and families, detect cancers earlier, and formulate more-effective individualized treatment protocols.

Roughly 5 to 10 percent of all colorectal cancers (CRCs) are considered hereditary and result from mutations and defects in specific genes. Another 25 to 30 percent of patients with CRC may have a family member with a diagnosis of CRC but no known genetic alterations.

A group of inherited syndromes has been associated with a 70 to 100 percent lifetime risk of CRC development, with many of these syndromes also carrying an increased risk of extraintestinal malignancies. These inherited syndromes include:

- Lynch syndrome

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

- MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP)

- Several hamartomatous polyposis conditions such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS), juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS) and Cowden's syndrome

Using family history and appropriate genetic testing to identify patients with these syndromes can help clinicians estimate a patient's cancer risk and determine appropriate cancer screening, surveillance or preventive interventions. Established in August 2017, Mayo Clinic's multidisciplinary inherited cancers clinic seeks to advance the understanding of hereditary colorectal cancers and their genetic basis to provide comprehensive, effective cancer detection, surveillance and clinical management for these patients.

"Because a substantial cancer risk is associated with these genetic mutations and hereditary syndromes, these patients require early detection and intense surveillance to prevent and manage several complex, life-threatening malignancies," says Niloy Jewel Samadder, M.D., a gastroenterologist specializing in inherited cancers at Mayo Clinic's campus in Arizona. Dr. Samadder and Mayo gastroenterologists Lisa A. Boardman, M.D., in Rochester, Minnesota, and Douglas L. Riegert-Johnson, M.D., in Jacksonville, Florida, co-lead the inherited cancers clinic at Mayo Clinic's campuses in Minnesota, Arizona and Florida.

Individuals with hereditary cancers typically present with more than one primary cancer, specific combinations of cancers, such as colon and endometrial cancers, and rare cancers. According to Dr. Samadder, these characteristics and other unique challenges associated with these cancers make consultation at a multispecialty clinic highly advantageous.

At Mayo Clinic, care of individuals with hereditary cancers often involves consultation with specialists from genetics, gastroenterology, oncology, gynecology, colorectal surgery and pathology, and with staff from Mayo Clinic's tumor board. Specific services provided by the inherited cancers clinic include:

- Personalized risk assessment for any type of cancer or tumor risk

- Coordination of genetic testing

- Tailored cancer screening recommendations

- Communication of information through the family

- High-risk follow-up cancer screening with Mayo physicians

- Discussion at tumor board for complex cases involving medical and surgical decision-making

- Multidisciplinary team approach

- Referral to clinical trials for research as needed

"Using available tools such as simple questionnaires of personal and family history of cancer in outpatient settings helps us improve the identification of high-risk patients and families, detect cancers earlier, and formulate more-effective individualized treatment protocols," says Dr. Samadder.

Additional programs

As the inherited cancers clinic continues to evolve, staff members are developing several additional related programs and services:

- A program responsible for coordinating routine immunohistochemistry testing of all surgically removed colorectal and endometrial tumors to aid in the identification of Lynch syndrome (launched in 2017 across Mayo Clinic's campuses in Arizona, Florida and Minnesota)

- A familial cancers tumor board to facilitate discussion of hereditary cancer cases with multispecialty input

- Telegenetics and outreach services to serve patients seen in Mayo Clinic Health System practices and regional hospitals

- A cancer registry and biorepository to support related research

- Educational offerings, including rotations for medical residents, subspecialty fellow and fellowships, and plans for collaboration with Arizona State University College of Health Solutions to initiate a genetic counseling program

In an article published in The American Journal of Gastroenterology, Dr. Samadder and co-authors provide a comprehensive overview of the genetics, surveillance and management of the more-common hereditary colorectal polyposis and cancer syndromes. Below is an abridged list of the cancers the authors discussed and an overview of related causes, diagnostic criteria and cancer surveillance recommendations associated with these syndromes.

Lynch syndrome

Accounting for about 2 to 4 percent of all CRCs, Lynch syndrome is the most common cause of hereditary colon cancer. Lynch syndrome is associated with predominately right-sided colon cancer. Individuals with Lynch syndrome are also at increased risk of extracolonic cancers, including cancers of the endometrium, ovaries, stomach, small intestine, hepatobiliary tract, urinary tract and central nervous system.

Genetic causes:

- An autosomal dominant condition caused by a DNA mismatch repair error that leads to mutations in one of five genes — MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 and EPCAM

Diagnosis:

- Early identification of patients carrying mutations accomplished using the Amsterdam and revised Bethesda criteria

Cancer surveillance:

- Colonoscopy recommended every one to two years in confirmed mutation carriers, beginning at age 20 to 25

- Currently no universal guidelines to guide screening for extracolonic cancers

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

The second most common form of hereditary CRC, FAP accounts for about 1 percent of all CRCs. Classic FAP is characterized by the presence of hundreds to thousands of adenomatous polyps throughout the colon and rectum that generally develop during adolescence. If colectomy is not performed, lifetime risk of colon cancer can reach 100 percent.

Individuals with FAP also have a small potential risk of extracolonic cancers, including hepatoblastomas, osteomas and desmoid tumors, as well as cancers of the stomach and pancreas. Attenuated FAP (AFAP) is a milder form of the disease that typically presents after age 25, with a lower lifetime polyp burden, averaging between 10 and 100 adenomatous polyps.

Genetic causes:

- Autosomal dominant conditions generally caused by germline mutations in the APC gene, a tumor suppressor gene associated with the Wnt signaling pathway

- When APC germline mutations not present, polyposis conditions may be associated with other genes, including POLE, POLD1 and GREM1

For diagnosis, genetic testing for FAP and AFAP is recommended:

- When single colonoscopy detects more than 10 cumulative adenomatous polyps

- For individuals with 10 or more adenomas and a personal history of CRC

- For individuals found to have more than 20 adenomatous polyps during their lifetime

- For patients diagnosed with FAP and at-risk family members

Cancer surveillance:

- For individuals with an APC mutation or with a family history of clinically diagnosed classic FAP, annual colonoscopy beginning around ages 10 to 12 years, ultimately leading to colectomy in those with polyposis too great to control via endoscopy

- For individuals with AFAP, colonoscopy every one to two years, beginning during the late teen years to early 20s

- For extracolonic cancers, recommended screenings include upper endoscopy, thyroid ultrasound and consideration for abdominal ultrasound in children

MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP)

Associated with a lifetime CRC risk of 80 percent, MAP sometimes resembles FAP and AFAP, with multiple adenomatous polyps noted on colonoscopy, usually 15 to 100 during a lifetime. Individuals with MAP may also have a higher prevalence of serrated polyps, duodenal polyposis and carcinoma. Reported extracolonic cancers in patients with MAP include ovarian, bladder, skin and breast cancers.

Causes and genetic diagnosis:

- An autosomal recessive condition caused by biallelic mutations to the DNA base excision repair gene MUTYH

Testing for MUTYH gene mutations is recommended for individuals who clinically present with one or more of these criteria:

- More than 20 colorectal adenomas

- Known family history of MAP

- 10 to 20 adenomas

- Diagnostic criteria for serrated polyposis syndrome with some adenomas noted on exam

Cancer surveillance:

- For individuals with homozygous MUTYH mutation, colonoscopy starting at age 25 to 30 years and repeated every two to three years if negative, and every one to two years if polyps are found

- For individuals with monoallelic MUTYH mutation, colonoscopy starting at age 40 years and repeated every five years

- For individuals with duodenal polyposis and carcinoma, baseline upper endoscopy beginning at age 30 to 35 years, with future screening dependent upon findings

- Screening timing and frequency influenced by family history and by the number and types of polyps identified on exam

Hamartomatous polyposis syndrome

This syndrome has three forms: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS), juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS) and Cowden's syndrome.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS)

PJS is characterized by the presence of hamartomatous polyps within the gastrointestinal tract and the appearance of mucocutaneous melanin pigmentation. PJS is associated with an increased lifetime risk of both gastrointestinal cancers (colon, pancreas, gastroesophageal, small bowel and stomach) and extraintestinal malignancies (breast, gynecological, lung and testicular).

Causes and genetic diagnosis:

- Rare, autosomal dominant conditions found in 50 to 70 percent of individuals with PJS, related to mutations of the STK11 (previously called LKB1) tumor suppressor gene

Clinical criteria for diagnosis confirmed by two or more of the following criteria:

- Two or more PJS-type hamartomatous polyps of the small intestine

- Mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation of the mouth, lips, nose, eyes, genitalia or fingers

- Family history of PJS

Cancer surveillance:

- Upper endoscopy and colonoscopy by late teen years, repeating every two to three years for surveillance if normal

- Small bowel assessment via baseline CT or MRI enterography, performed by late teen years and repeated every two to three years thereafter

- Pancreatic cancer screening via MRI and MRCP or endoscopic ultrasonography, every one to two years beginning by age 30 to 35

Juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS)

JPS is characterized by the presence of at least three to five juvenile polyps in the gastrointestinal tract that are typically large and pedunculated. Histologically, JPS polyps show evidence of inflammation of lamina propria, thick mucin-filled cystic glands, with minimal smooth muscle proliferation.

JPS is associated with an increased risk of CRC and other gastrointestinal cancers (small bowel, stomach and pancreas). A subset of individuals with JPS experience hemorrhagic telangiectasia, leading to chronic nosebleeds and other severe bleeding problems caused by blood vessel abnormalities.

Causes and genetic diagnosis:

- Associated with mutations in the SMAD4 and BMPR1A genes

Clinical criteria for diagnosis confirmed by meeting one or more of these criteria:

- At least three to five juvenile colon polyps

- Multiple juvenile polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract

- Any number of juvenile polyps in an individual with a family history of JPS

Cancer surveillance:

- Colonoscopy and upper endoscopy, starting at age 15 and repeated annually if polyps are found, and every two to three years if no polyps are noted

- Screening for small bowel or pancreatic cancer not currently recommended

- Guidelines for extracolonic cancers available at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Serrated polyposis syndrome

Previously known as hyperplastic polyposis syndrome, this condition is characterized by multiple serrated colon polyps and an increased lifetime risk of CRC.

Causes:

- Genetic makeup is poorly understood; with no single gene identified, clinical criteria are used for the diagnosis.

Diagnosis confirmed by one or more of these criteria:

- Five or more serrated polyps proximal to sigmoid colon with two or more larger than 10 mm in size

- Presence of any serrated polyps proximal to sigmoid colon and a first-degree relative with serrated polyposis syndrome

- More than 20 serrated polyps of any size distributed throughout colon

Cancer surveillance:

- Colonoscopy at least every one to three years, starting at age 40 and repeated every one to three years if polyps found, or every five years if no polyps found; no special screening guidelines currently for extracolonic cancer surveillance

For more information

Kanth P, et al. Hereditary colorectal polyposis and cancer syndromes: A primer on diagnosis and management. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017;112:1509.