Diagnosis

Pituitary tumors often aren't noticed or detected. Tumors that make hormones are called functioning adenomas. Larger tumors are called macroadenomas. Both of these tumors can cause symptoms that look like other health conditions. These tumors also tend to grow slowly over time.

Small pituitary tumors that don't make hormones, called nonfunctioning microadenomas, often don't cause any symptoms at all. When these small tumors are found, it's usually during an imaging exam, such as an MRI or a CT scan, that's done for another reason.

Pituitary tumor versus craniopharyngioma

Both pituitary tumors and craniopharyngiomas grow near the pituitary and can cause similar symptoms such as headaches and vision changes. And they both can affect hormones. These similarities can make it easy to confuse them, but they are not the same.

A pituitary adenoma begins in the pituitary's hormone-making cells. The adenoma may produce extra hormone. Many pituitary adenomas are treated with endoscopic surgery. Some types are treated with medicines.

A craniopharyngioma grows from leftover embryonic tissue near the pituitary stalk. This type of tumor often contains cysts. A craniopharyngioma does not make hormones, but it may change typical hormone function. Treatment for craniopharyngioma usually involves surgery and radiation. MRI and CT scans may be used to help tell them apart.

To check for a pituitary tumor, your healthcare professional will likely talk with you about your personal and family medical history and do a physical exam. Testing to detect a pituitary tumor also may include:

-

Blood tests. Blood tests can show whether your body has too much or too little of certain hormones. In some cases, a high hormone level may be enough for your healthcare professional to diagnose a pituitary tumor.

For other hormones, such as cortisol, more tests may be needed to confirm whether the high level is caused by a pituitary tumor or by another condition.

Results that show hormone levels are too low need to be followed with other tests, usually imaging exams, to see if a pituitary adenoma may be the cause of those test results.

- Urine tests. A urine test can help check for a type of pituitary adenoma that makes too much of the hormone ACTH. Too much ACTH leads to too much cortisol in the body and causes Cushing disease.

- Brain MRI scan. A magnetic resonance imaging scan, also called an MRI scan, takes detailed images of the body's organs and tissues. A brain MRI can help detect a pituitary tumor and show its location and size. During an MRI, a small amount of contrast is injected into a vein. The contrast travels in your blood and helps certain tissues show up more clearly.

- Brain CT scan. A computerized tomography scan, also called a CT scan, combines multiple X-rays to create cross-sectional images. CT scans are not used as often as MRI scans for finding pituitary tumors. However, a CT scan may be helpful when planning surgery.

- Vision testing. Some pituitary tumors can affect your eyesight, especially your ability to see to the side. An eye exam can help check for this.

What does a pituitary tumor look like on MRI?

On a pituitary MRI, a small tumor called a microadenoma often shows up as a tiny spot. The tumor and the rest of the gland take up the contrast material differently. So right after the contrast is given, this tiny tumor spot usually looks a little darker on the images. A larger tumor, known as a macroadenoma, can make the pituitary gland look bigger and can push aside parts of the gland. It also may press on nearby areas, such as the nerves that help you see.

How can you see a pituitary tumor on MRI?

MRI scans take very detailed pictures of the brain using thin slices. A healthcare professional takes pictures before and after giving the contrast to help see the tumor. For very small tumors, a fast type of scan takes several pictures very quickly right after the contrast is injected. Microadenomas absorb the contrast more slowly, so they look darker than the rest of the gland right after the contrast is given.

Bigger tumors usually are easy to spot. The MRI shows how close the tumors are to the nerves that help you see and to nearby blood vessels. Seeing the tumor's location on MRI is necessary for surgical planning and for protecting your vision and overall health during treatment.

Blood tests for pituitary adenoma: What do they check?

Blood, urine and saliva tests look for two things:

- Extra hormone made by the tumor. Common tests look at prolactin, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) for growth hormone, and thyroid tests such as TSH and free T4. Cortisol and ACTH tests measure how well the pituitary and adrenal glands make and control cortisol, a hormone linked to stress and metabolism.

- Low levels of pituitary hormones. Blood tests can check levels of cortisol, free T4 and TSH, sex hormones such as testosterone or estradiol with luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone, and IGF-1 to look for hormone deficiencies that may need treatment.

Your healthcare professional may refer you to a specialist in hormone disorders, called an endocrinologist, for more testing.

More Information

Treatment

Most pituitary tumors are not cancer and may not need treatment if they don't cause symptoms. In many cases, regular monitoring is enough.

If treatment is needed, your care team considers things such as the type of tumor, its size and location, how fast it's growing, and whether it's affecting your hormone levels. Your age and overall health also help guide treatment decisions.

The goals of treatment are to:

- Return hormone levels to a healthy range.

- Prevent more damage to the pituitary gland and restore its regular function.

- Ease symptoms caused by tumor pressure or keep them from getting worse.

If your pituitary adenoma needs treatment, your care team may recommend surgery, medicines or radiation therapy. You'll be supported by a team of experts, which may include a:

- Hormone disorder specialist, called an endocrinologist.

- Brain surgeon, called a neurosurgeon.

- Nose and sinus surgeon, called an ENT surgeon.

- Radiation therapy specialist, called a radiation oncologist.

Can a pituitary tumor shrink on its own?

It's uncommon. Tumors called microprolactinomas have been observed to shrink or even go away on their own in rare cases. Prolactin-secreting tumors much more often shrink with medicine.

Surgery

Surgery can treat a pituitary tumor by removing it. This is sometimes called a tumor resection.

What size pituitary tumor should be removed?

There isn't a rule for the exact size that requires removal. Surgery usually is recommended when the tumor:

- Presses on the optic nerves or affects vision.

- Causes the body to make too much of certain hormones.

- Pushes on your pituitary gland and lowers your hormone levels.

- Continues to grow after treatment.

- Bleeds and causes symptoms.

- Causes other symptoms, such as headache or facial pain.

Larger tumors are more likely to press on nearby structures. To decide whether surgery is the best treatment, healthcare teams consider a combination of factors. These factors include symptoms, hormone tests, growth and scan findings — not just size.

Results after surgery typically depend on the adenoma type, its size and location, and whether the tumor has grown into tissues around it.

Surgeries to remove a pituitary tumor include transnasal transsphenoidal surgery and craniotomy.

Transnasal transsphenoidal surgery

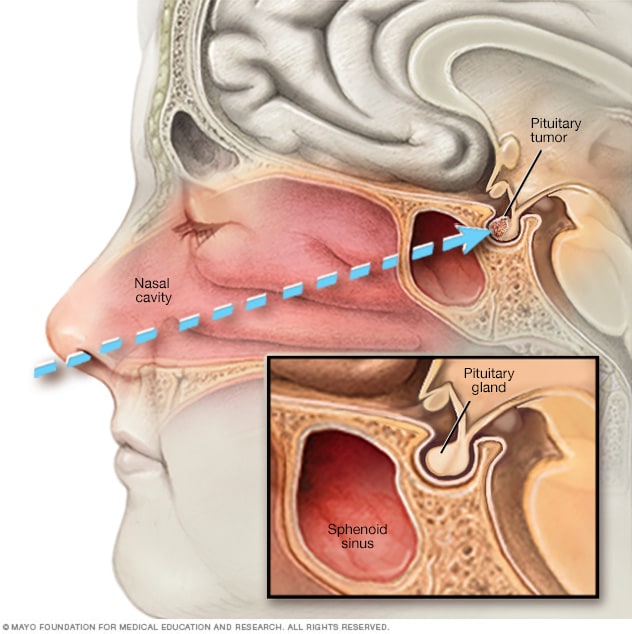

Endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal surgery

Endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal surgery

In endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal surgery, a surgical instrument is placed into the nasal cavity through the nostril and alongside the nasal septum to access a pituitary tumor.

Transnasal transsphenoidal surgery is the most common procedure for pituitary tumors. It allows surgeons to reach the tumor through the nose.

During the surgery, surgeons remove the tumor by going through the nostrils. The surgery doesn't require any external cuts and won't leave a scar you can see. The brain itself is not touched during this procedure. A brain surgeon often works with a nose and sinus expert to perform this surgery safely.

Large pituitary tumors may be harder to remove with this surgery. That's especially true if the tumor has spread to nearby nerves, blood vessels or other parts of the brain.

Is the transsphenoidal resection of a pituitary adenoma the same as endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal surgery?

In general, yes. Transsphenoidal resection means the surgeon reaches the pituitary through the nose and sphenoid sinus. That route can be done with a microscope or with an endoscope. Endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal surgery reaches the pituitary with the same route but uses a thin, flexible camera. This option gives a wide, closeup view.

Transcranial surgery

Transcranial surgery is sometimes called craniotomy. It's used less often than transnasal transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors.

Transcranial surgery may be recommended for large pituitary tumors. Or it may be recommended for tumors that have spread to nearby nerves or brain tissue. This surgery allows the surgeon to better see the full size of the tumor and the parts of the brain around it. During the surgery, the surgeon makes a cut in the scalp and removes the tumor through the upper part of the skull.

Transnasal transsphenoidal surgery and transcranial surgery are generally safe. Complications are not common. But as with any surgery, there are risks. Possible complications after pituitary tumor surgery include:

- Bleeding.

- Infection.

- Side effects from anesthesia medicine, which is used to keep you in a sleep-like state during surgery.

- Temporary headache and nasal congestion.

- Brain injury.

- Vision changes, such as double vision or vision loss.

- Damage to the pituitary gland.

- A condition called diabetes insipidus.

Diabetes insipidus happens when the pituitary gland cannot make enough of the hormone vasopressin. This hormone helps your body balance its fluids. When vasopressin levels are too low, your body makes too much urine, which can lead to extreme thirst and dehydration. Diabetes insipidus after pituitary surgery usually is short term. It often goes away without treatment within a few days. If it lasts longer, your care team may recommend medicine to replace the missing hormone. In most cases, the condition goes away after a few weeks or months.

If your healthcare professional suggests surgery to treat a pituitary tumor, ask questions to help you prepare. Find out which type of surgery may be best for you. Talk about the possible risks and side effects. Also ask about what you can expect during recovery.

What is the survival rate for pituitary tumor surgery?

Prognosis and success rate depends on tumor type, size, where it extends, and the experience of the team performing the surgery. Many people with small, hormone-secreting tumors go into hormone remission after surgery. For Cushing disease, about 70% to 90% of people achieve remission when they have surgery in an experienced surgical center.

Vision often improves after surgery to remove a tumor that was pressing on the nerves that help you see. About 70% to 90% of people with vision issues see improvement. But full recovery is less likely if the nerves were compressed for a long time. Some tumors, especially larger or invasive ones, need medicines or focused radiation after surgery. Sometimes both medicines and radiation are needed.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy sources of radiation to treat pituitary tumors. It may be used after surgery or on its own if surgery isn't an option.

Radiation therapy can be helpful if a pituitary tumor:

- Could not be completely removed with surgery.

- Comes back after surgery.

- Causes symptoms that medicines don't relieve.

The goal of radiation therapy for pituitary adenomas is to control adenoma growth or to stop the adenoma from making hormones.

Methods of radiation therapy that can be used to treat pituitary tumors include:

- Stereotactic radiosurgery. This type of radiation treatment uses a single, focused dose of radiation to treat the tumor. Even though it's called surgery, no cutting is involved. To guide the treatment, healthcare professionals use brain imaging and place a special frame on your head. This frame helps aim the radiation beams precisely at the tumor and is removed right after the procedure. Because the radiation is aimed so precisely, nearby healthy brain tissue is exposed to very little radiation. This lowers the risk of damage to healthy tissue.

- External beam radiation. This method is called fractionated radiation therapy. It gives small doses of radiation over time instead of all at once. It's usually given five times a week for 5 to 6 weeks.

- Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). This type of radiation therapy uses a computer to shape and direct radiation beams around the tumor from many angles. The strength of the beams can be controlled to reduce damage to healthy tissue nearby.

- Proton beam therapy. This radiation treatment uses positively charged ions called protons to target tumors. Proton beams stop after releasing their energy within the tumor. That helps protect healthy tissue nearby and may lower the risk of side effects. Proton beam therapy requires special equipment and isn't widely available.

Potential side effects and complications of radiation therapy for pituitary adenomas can include:

- Damage to the pituitary gland, which may limit your body's ability to make hormones.

- Damage to healthy tissue near the pituitary gland.

- Vision changes if the optic nerves are damaged.

- Damage to other nerves close to the pituitary gland.

- Slightly increased risk of developing a brain tumor.

If your care team recommends radiation therapy, a specialist called a radiation oncologist can help you understand the possible benefits and risks. Radiation therapy for pituitary adenomas works slowly, so it can take months or years to see the full results. Side effects also may take a long time to appear. That's why it's important to have regular checkups after treatment to watch for any hormone changes or other issues.

Medicines

Some pituitary tumors can be treated with medicines. They can help lower the amount of hormones the tumor makes. In some cases, they also may help shrink the tumor.

Medicines for pituitary tumors that make prolactin

Medicines for prolactin-producing tumors often can achieve all the goals of therapy. These goals include returning hormone levels to the healthy range, preventing more damage to the pituitary gland and relieving symptoms of pressure from the tumor. Medicines may make the need for surgery or radiation unnecessary for many people. They also can often shrink the tumor. The following medicines are used to lower the amount of prolactin that a pituitary adenoma makes:

- Cabergoline.

- Bromocriptine.

Possible side effects include:

- Dizziness.

- Drowsiness.

- Upset stomach or vomiting.

- Mood disorders, including depression.

- Headache.

- Weakness.

Some people also may develop behaviors that are hard to control, such as gambling, while taking these medicines. These behaviors are called impulse control disorders. People of childbearing age who take these medicines should discuss birth control options with their healthcare professionals. They also should tell their healthcare professionals if they are considering getting pregnant.

Medicines for pituitary tumors that make adrenocorticotropic hormone

Tumors that make adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) cause the body to make too much cortisol. This can lead to a condition known as Cushing disease. Medicines that can lower cortisol levels include:

- Ketoconazole.

- Metyrapone (Metopirone).

- Osilodrostat (Isturisa).

Some possible side effects of these medicines include upset stomach, headache and fatigue.

Another medicine called mifepristone (Korlym, Mifeprex) may be used to treat Cushing disease in people who also have type 2 diabetes or trouble managing blood sugar. Mifepristone doesn't lower the amount of cortisol the body makes. Instead, it blocks the effects of cortisol on the body's tissues.

Side effects of mifepristone include:

- Tiredness.

- Weakness.

- Upset stomach.

- Heavy vaginal bleeding.

The medicine pasireotide (Signifor) helps lower the amount of ACTH made by a pituitary adenoma, which in turn lowers cortisol levels. It's taken as a shot twice a day. Healthcare professionals may suggest pasireotide when surgery to remove an adenoma doesn't work or isn't an option.

Possible side effects of pasireotide include:

- Diarrhea.

- Upset stomach.

- High blood sugar.

- Headache.

- Stomach pain.

- Gallstones.

Pituitary tumors that make growth hormone

Two kinds of medicine can treat pituitary tumors that make growth hormone. Healthcare professionals often prescribe these medicines if surgery doesn't bring growth hormone levels back to a healthy range.

-

Somatostatin analogs. This type of medicine lowers the amount of growth hormone that the tumor makes. It also may decrease the size of a pituitary adenoma. Somatostatin analogs include:

- Octreotide (Mycapssa, Sandostatin).

- Lanreotide (Somatuline Depot).

- Paltusotine (Palsonify).

Taking one of these medicines signals the pituitary gland to make less growth hormone. Most of these medicines are given as a shot, usually every four weeks. Mycapssa is a capsule taken by mouth twice a day. It works the same way as the shot and has similar side effects.

Possible side effects of somatostatin analogs include:

- Upset stomach or vomiting.

- Diarrhea.

- Stomach pain.

- Dizziness.

- Headache.

- Pain at the site of the shot.

- Gallstones.

- Worsening diabetes.

Many of these side effects improve over time.

- Pegvisomant (Somavert). This medicine blocks the effect of too much growth hormone on the body. It's taken as a shot every day. In some people, this medicine can cause mild liver damage.

Pituitary hormone replacement

The pituitary gland helps control many important body functions, such as growth and reproduction. A tumor in this gland or the treatments used to remove it can sometimes change how the gland works. If that causes your hormone levels to drop too low, you may need to take hormone replacement therapy to help bring your hormone levels back to a healthy range.

Hormone replacement may be needed for a limited time, or it may be lifelong. Sometimes hormone replacement is not needed until long after treatment is finished. This reinforces the need for regular long-term follow-up after treatment.

Watchful waiting

In watchful waiting, also called observation or deferred therapy, you may need regular follow-up tests to see if a tumor grows or if hormone levels change. This may be a good option for you if an adenoma isn't causing any symptoms or health concerns. Talk to your healthcare professional about the benefits and risks of watchful waiting versus treatment in your situation.

More Information

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Living with a pituitary adenoma can be difficult. But you can take steps to feel your best and support your overall health:

- Get regular physical activity. For people with pituitary adenomas, movement may increase energy and improve sleep and mood. Ask your care team what types of activity are safe for you, especially if you're recovering from surgery or radiation.

- Eat a healthy diet. A balanced diet supports your body during treatment and recovery. If you have a pituitary adenoma that causes Cushing disease, ask your care team about ways to protect your bone health. You may need more calcium and vitamin D to help keep your bones strong.

- Follow your treatment plan. Take medicines exactly as prescribed. Attend all follow-up appointments so your care team can track your progress and adjust treatment if needed.

- Watch for hormone symptoms. Pituitary adenomas can affect hormone levels. Let your healthcare professional know if you notice changes in your weight, mood, energy levels, vision or menstrual cycle.

Coping and support

It's natural for you to have questions when you're diagnosed with a pituitary tumor. The process can be overwhelming and even scary at times. Learning more about your condition can help you feel more confident and in control.

You might find it helpful to share your feelings with other people who are in similar situations. Check to see if support groups for people with pituitary tumors are available in your area. Hospitals often sponsor these groups. Ask your healthcare professional if there are groups or other resources in your area that can provide the support you need.

What does life look like for someone after pituitary tumor surgery?

Most people go home within a few days. It's common to have a stuffy nose, mild headache and sore throat for a short time. You'll have follow-up visits to check healing, vision and hormones. Some people need temporary or long-term hormone replacement, and you'll have repeat MRIs to monitor the tumor site.

How long does recovery take following pituitary tumor surgery?

Recovery varies. Many people can get back to daily activities within a few weeks while the nose and sinuses heal. Your care team will give specific instructions about lifting, nose blowing and exercise during that period.

Do some people lose weight after pituitary tumor surgery?

It depends on the tumor type. After successful treatment for Cushing disease, weight often goes down over time as cortisol levels return to a healthy level. In other tumor types, weight may not change much. Tell your care team about any rapid weight change so they can check hormones and medicines.

Is it expected for someone to have personality changes after pituitary tumor surgery?

Mood changes can happen for a while as hormones reset and you recover from surgery. Most people improve over weeks to months as hormones get to a healthy level. People treated for Cushing disease may have fatigue, low mood or irritability during recovery from high cortisol. It may take up to a year to feel like your previous self. Let your care team know if mood or thinking troubles are strong or persistent. Treatment and counseling can help.

Are there any foods to be avoided if someone has a pituitary tumor?

There isn't a special pituitary diet. A balanced diet is fine for most people. Some medicines used for pituitary tumors have food or drug interactions, so follow the specific guidance you're given.

What is the life expectancy after a pituitary tumor is removed? Does this change if the tumor becomes cancerous?

When someone is diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma, which is a benign tumor, large studies show that more than 80% of people are alive 10 years later. Research does show that if the surgery fully removes the tumor, hormone levels return to normal, and the person is young and otherwise healthy, many live a normal lifespan. This survival rate is regardless of treatment.

However, there's no single reliable number for how long people live after surgery alone, because research doesn't always study outcomes of people with only surgery as treatment.

Pituitary cancer, or pituitary carcinoma, is very rare. Outcomes vary, but survival is significantly shorter than for adenomas. Studies show that the median survival after the cancer has spread is between 1.5 and 3.6 years.

Preparing for your appointment

You'll likely start by seeing your primary healthcare professional. You may be referred to one or more specialists. These may include an eye doctor called an ophthalmologist, a brain surgeon called a neurosurgeon, or a hormone specialist called an endocrinologist.

Here's some information to help you prepare for your appointment.

What you can do

When you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as not eating before having a specific test. Make a list of:

- Your symptoms, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for your appointment.

- Key personal details, including major stresses or recent life changes and family medical history.

- Medicines, vitamins or supplements you take, including doses.

- Questions to ask your healthcare professional.

If possible, bring a family member or friend with you. This person can help you remember the information you get during your visit.

For a pituitary tumor, questions to ask your healthcare professional include:

- What could be causing my symptoms or condition?

- Are there other possible causes?

- What kinds of specialists should I see?

- What tests do I need?

- What treatments do you recommend?

- Are there other options besides the approach you're suggesting?

- I have other health conditions. How can I manage them together?

- Are there restrictions I need to follow?

- Are there brochures or other printed materials I can have? What websites do you recommend?

You also can ask any other questions that are on your mind.

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare professional likely will ask you a number of questions. These may include:

- When did your symptoms begin?

- Do your symptoms come and go, or are they there all the time?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- Have you noticed anything that makes your symptoms better?

- Have you noticed anything that makes your symptoms worse?

- Have you had imaging tests done of your head for any reason in the past?

- What are your plans for having children in the future?

Dec. 23, 2025