Diagnosis

Neurological exam

Neurological exam

A complete neurological exam and medical history are needed to diagnose MS.

Multiple sclerosis FAQs

Neurologist Oliver Tobin, M.B., B.Ch., B.A.O., Ph.D., answers the most frequently asked questions about multiple sclerosis.

So people who are overweight have a higher chance of developing MS and people who have MS who are overweight tend to have more active disease and a faster onset of progression. The main diet has been shown to be neuroprotective is the Mediterranean diet. This diet is high in fish, vegetables, and nuts, and low in red meat.

So this question comes up a lot because patients who have multiple sclerosis can sometimes get a transient worsening of their symptoms in heat or if they exercise strenuously. The important thing to note is that heat does not cause an MS attack or MS relapse. And so it's not dangerous. You're not doing any permanent damage if this occurs. Exercise is strongly recommended and is protective to the brain and spinal cord.

Scientists do not yet know which stem cells are beneficial in MS, what route to give them or what dose to give them or what frequency. So at the moment, stem cell treatments are not recommended outside of the context of a clinical trial.

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder or NMOSD and MOG-associated disorder can give features similar to multiple sclerosis. These are more common in people of Asian or African-American ethnicity. And your doctor may recommend blood tests to exclude these disorders.

Well, the first drug approved by the FDA for treatment of multiple sclerosis was in 1993. Since then, over 20 drugs have become available for treatment of MS. And the potency of these drugs has increased over time to the point where we can almost completely suppress the inflammatory component of the disease. This would not be possible if patients like you did not enroll in research studies. There are many different types of research studies, not just drug trials, but also observational studies, as all of these enhance our understanding of the disease, hopefully to lead to even better cures for multiple sclerosis.

Well, the most important thing about having a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis is that you are at the center of your medical team. A comprehensive MS center is the best place for management of multiple sclerosis, and this typically includes physicians with expertise in multiple sclerosis, neurologists, but also urologists, physiatrists or physical medicine and rehabilitation providers, psychologists, and many other providers who have specialty interest in multiple sclerosis. Engaging this team around you and your particular needs will improve your outcomes over time.

There are no specific tests for MS. Instead, a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis often relies on ruling out other conditions that might produce similar signs and symptoms, known as a differential diagnosis.

Your doctor is likely to start with a thorough medical history and examination.

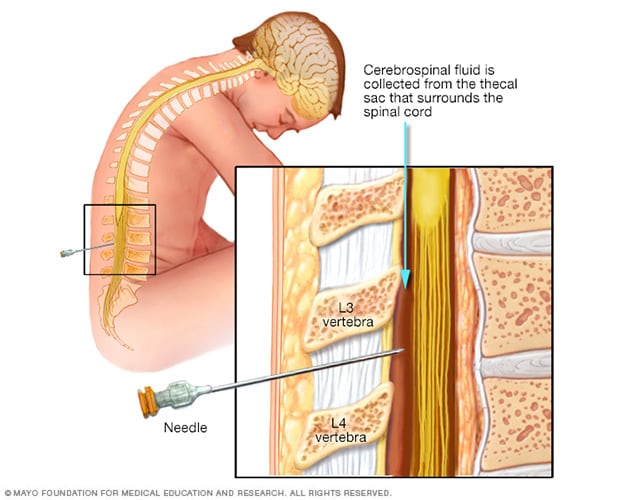

Lumbar puncture (spinal tap)

Lumbar puncture (spinal tap)

During a spinal tap, known as a lumbar puncture, you typically lie on your side with your knees drawn up to your chest. Then a needle is inserted into your spinal canal — in your lower back — to collect cerebrospinal fluid for testing.

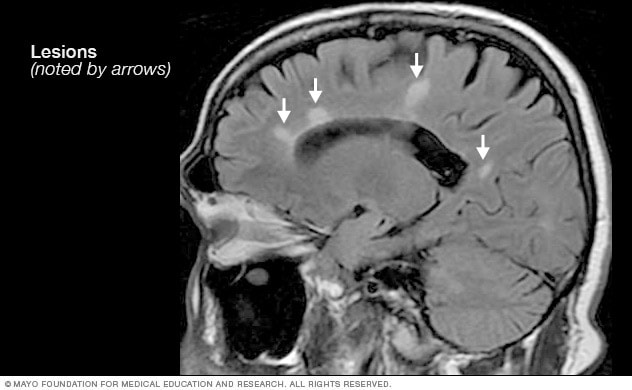

MRI multiple sclerosis lesions

MRI multiple sclerosis lesions

Brain MRI scan showing white lesions associated with multiple sclerosis.

Your doctor may then recommend:

- Blood tests, to help rule out other diseases with symptoms like MS. Tests to check for specific biomarkers associated with MS are currently under development and may also aid in diagnosing the disease.

- Spinal tap (lumbar puncture), in which a small sample of cerebrospinal fluid is removed from your spinal canal for laboratory analysis. This sample can show abnormalities in antibodies that are associated with MS. A spinal tap can also help rule out infections and other conditions with symptoms like MS. A new antibody test (for kappa free light chains) may be faster and less expensive than previous spinal fluid tests for multiple sclerosis.

- MRI, which can reveal areas of MS (lesions) on your brain, cervical and thoracic spinal cord. You may receive an intravenous injection of a contrast material to highlight lesions that indicate your disease is in an active phase.

- Evoked potential tests that record the electrical signals produced by your nervous system in response to stimuli may be done. An evoked potential test may use visual stimuli or electrical stimuli. In these tests, you watch a moving visual pattern, as short electrical impulses are applied to nerves in your legs or arms. Electrodes measure how quickly the information travels down your nerve pathways.

In most people with relapsing-remitting MS, the diagnosis is straightforward and based on a pattern of symptoms consistent with the disease and confirmed by brain imaging scans, such as an MRI.

Diagnosing MS can be more difficult in people with unusual symptoms or progressive disease. In these cases, further testing with spinal fluid analysis, evoked potentials and additional imaging may be needed.

Brain MRI is often used to help diagnose multiple sclerosis.

More Information

Treatment

There is no cure for multiple sclerosis. Treatment typically focuses on speeding recovery from attacks, reducing new radiographic and clinical relapses, slowing the progression of the disease, and managing MS symptoms. Some people have such mild symptoms that no treatment is necessary.

Multiple sclerosis research laboratory at Mayo Clinic

Treatments for MS attacks

- Corticosteroids, such as oral prednisone and intravenous methylprednisolone, are prescribed to reduce nerve inflammation. Side effects may include insomnia, increased blood pressure, increased blood glucose levels, mood swings and fluid retention.

- Plasma exchange (plasmapheresis). The liquid portion of part of your blood (plasma) is removed and separated from your blood cells. The blood cells are then mixed with a protein solution (albumin) and put back into your body. Plasma exchange may be used if your symptoms are new, severe and haven't responded to steroids.

Treatments to modify progression

There are several disease modifying therapies (DMTs) for relapsing-remitting MS. Some of these DMTs can be of benefit for secondary progressive MS, and one is available for primary progressive MS.

Much of the immune response associated with MS occurs in the early stages of the disease. Aggressive treatment with these medications as early as possible can lower the relapse rate, slow the formation of new lesions, and potentially reduce risk of brain atrophy and disability accumulation.

Many of the disease-modifying therapies used to treat MS carry significant health risks. Selecting the right therapy for you will depend on careful consideration of many factors, including duration and severity of disease, effectiveness of previous MS treatments, other health issues, cost, and child-bearing status.

Treatment options for relapsing-remitting MS include injectable, oral and infusions medications.

Injectable treatments include:

-

Interferon beta medications. These drugs used to be the most prescribed medications to treat MS. They work by interfering with diseases that attack the body and may decrease inflammation and increase nerve growth. They are injected under the skin or into muscle and can reduce the frequency and severity of relapses.

Side effects of interferons may include flu-like symptoms and injection-site reactions. You'll need blood tests to monitor your liver enzymes because liver damage is a possible side effect of interferon use. People taking interferons may develop neutralizing antibodies that can reduce drug effectiveness.

- Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone, Glatopa). This medication may help block your immune system's attack on myelin and must be injected beneath the skin. Side effects may include skin irritation at the injection site.

- Monoclonal antibodies. Ofatumumab (Kesimpta, Arzerra) targets cells that damage the nervous system. These cells are called B cells. Ofatumumab is given by an injection under the skin and can decrease multiple sclerosis brain lesions and worsening symptoms. Possible side effects are infections, local reactions to the injection and headaches.

Oral treatments include:

- Teriflunomide (Aubagio). This once-daily oral medication can reduce relapse rate. Teriflunomide can cause liver damage, hair loss and other side effects. This drug is associated with birth defects when taken by both men and women. Therefore, use contraception when taking this medication and for up to two years afterward. Couples who wish to become pregnant should talk to their doctor about ways to speed elimination of the drug from the body. This drug requires blood test monitoring on a regular basis.

- Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera). This twice-daily oral medication can reduce relapses. Side effects may include flushing, diarrhea, nausea and lowered white blood cell count. This drug requires blood test monitoring on a regular basis.

- Diroximel fumarate (Vumerity). This twice-daily capsule is similar to dimethyl fumarate but typically causes fewer side effects. It's approved for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS.

- Monomethyl fumarate (Bafiertam) was approved by the FDA as a delayed release medicine that has a slow and steady action. Because of its time release, it is hoped that side effects will be decreased. Possible side effects are flushing, liver injury, abdominal pain and infections.

-

Fingolimod (Gilenya). This once-daily oral medication reduces relapse rate.

You'll need to have your heart rate and blood pressure monitored for six hours after the first dose because your heart rate may be slowed. Other side effects include rare serious infections, headaches, high blood pressure and blurred vision.

- Siponimod (Mayzent). Research shows that this once-daily oral medication can reduce relapse rates and help slow progression of MS. It's also approved for secondary-progressive MS. Possible side effects include viral infections, liver problems and low white blood cell count. Other possible side effects include changes in heart rate, headaches and vision problems. Siponimod is harmful to a developing fetus, so women who may become pregnant should use contraception when taking this medication and for 10 days after stopping the medication. Some might need to have the heart rate and blood pressure monitored for six hours after the first dose. This drug requires blood test monitoring on a regular basis.

- Ozanimod (Zeposia). This oral medication decreases the relapse rate of multiple sclerosis and is given once a day. Possible side effects are an elevated blood pressure, infections and liver inflammation.

- Ponesimod (Ponvory). This oral medication is taken once a day with a gradually increasing dosing schedule. This medicine has a low relapse rate and has demonstrated fewer brain lesions than some other medications used to treat multiple sclerosis. The possible side effects are respiratory tract infections, high blood pressure, liver irritation and electrical problems in the heart that affect heart rate and rhythm.

- Cladribine (Mavenclad). This medication is generally prescribed as a second line treatment for those with relapsing-remitting MS. It was also approved for secondary-progressive MS. It is given in two treatment courses, spread over a two-week period, over the course of two years. Side effects include upper respiratory infections, headaches, tumors, serious infections and reduced levels of white blood cells. People who have active chronic infections or cancer should not take this drug, nor should women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Men and women should use contraception when taking this medication and for the following six months. You may need monitoring with blood tests while taking cladribine.

Infusion treatments include:

-

Natalizumab (Tysabri). This is a monoclonal antibody that has been shown to decrease relapse rates and slow down the risk of disability.

This medication is designed to block the movement of potentially damaging immune cells from your bloodstream to your brain and spinal cord. It may be considered a first line treatment for some people with severe MS or as a second line treatment in others.

This medication increases the risk of a potentially serious viral infection of the brain called progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in people who are positive for antibodies to the causative agent of PML JC virus. People who don't have the antibodies have extremely low risk of PML.

-

Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus). This treatment reduces the relapse rate and the risk of disabling progression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. It also slows the progression of the primary-progressive form of multiple sclerosis.

This humanized monoclonal antibody medication is the only DMT approved by the FDA to treat both the relapse-remitting and primary-progressive forms of MS. Clinical trials showed that it reduced relapse rate in relapsing disease and slowed worsening of disability in both forms of the disease.

Ocrelizumab is given via an intravenous infusion by a medical professional. Infusion-related side effects may include irritation at the injection site, low blood pressure, a fever and nausea, among others. Some people may not be able to take ocrelizumab, including those with a hepatitis B infection. Ocrelizumab may also increase the risk of infections and some types of cancer, particularly breast cancer.

-

Alemtuzumab (Campath, Lemtrada). This treatment is a monoclonal antibody that decreases annual relapse rates and demonstrates MRI benefits.

This drug helps reduce relapses of MS by targeting a protein on the surface of immune cells and depleting white blood cells. This effect can limit potential nerve damage caused by the white blood cells. But it also increases the risk of infections and autoimmune disorders, including a high risk of thyroid autoimmune diseases and rare immune mediated kidney disease.

Treatment with alemtuzumab involves five consecutive days of drug infusions followed by another three days of infusions a year later. Infusion reactions are common with alemtuzumab.

The drug is only available from registered providers, and people treated with the drug must be registered in a special drug safety monitoring program. Alemtuzumab is usually recommended for those with aggressive MS or as second line treatment for patients who failed another MS medication.

Recent developments or emerging therapies

Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor is an emerging therapy being studied in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis. It works by mostly modulating B cells, which are immune cells in the central nervous system.

Stem cell transplantation destroys the immune system of someone with multiple sclerosis and then replaces it with transplanted healthy stem cells. Researchers are still investigating whether this therapy can decrease inflammation in people with multiple sclerosis and help to "reset" the immune system. Possible side effects are fever and infections.

Researchers are learning more about how existing disease modifying therapies work to lessen relapses and reduce multiple sclerosis-related lesions in the brain. Further studies will determine whether treatment can delay disability caused by the disease.

For primary-progressive MS, ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy (DMT). Those who receive this treatment are slightly less likely to progress than those who are untreated.

For secondary progressive MS, some might consider the use of FDA-approved disease modifying therapies such as ozanimod, siponimod and cladribine, which can potentially slow down disabilities.

Treatments for MS signs and symptoms

Physical therapy for multiple sclerosis

Physical therapy for multiple sclerosis

Physical therapy can build muscle strength and ease some of the symptoms of MS.

-

Therapy. A physical or occupational therapist can teach you stretching and strengthening exercises and show you how to use devices to make it easier to perform daily tasks.

Physical therapy along with the use of a mobility aid, when necessary, can also help manage leg weakness and other gait problems often associated with MS.

- Muscle relaxants. You may experience painful or uncontrollable muscle stiffness or spasms, particularly in your legs. Muscle relaxants such as baclofen (Lioresal, Gablofen), tizanidine (Zanaflex) and cyclobenzaprine may help. Onabotulinumtoxin A treatment is another option in those with spasticity.

- Medications to reduce fatigue. Amantadine (Gocovri, Osmolex), modafinil (Provigil) and methylphenidate (Ritalin) have been used to reduce MS-related fatigue. However, a recent study did not find amantadine, modafinil or methylphenidate to be superior to a placebo in improving MS-related fatigue and caused more frequent adverse events. Some drugs used to treat depression, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, may be recommended.

- Medication to increase walking speed. Dalfampridine (Ampyra) may help to slightly increase walking speed in some people. Possible side effects are urinary tract infections, vertigo, insomnia and headaches. People with a history of seizures or kidney dysfunction should not take this medication.

- Other medications. Medications also may be prescribed for depression, pain, sexual dysfunction, insomnia, and bladder or bowel control problems that are associated with MS.

More Information

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Lifestyle and home remedies

To help relieve the signs and symptoms of MS, try to:

- Get plenty of rest. Look at your sleep habits to make sure you're getting the best possible sleep. To make sure you're getting enough sleep, you may need to be evaluated — and possibly treated — for sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea.

- Exercise. If you have mild to moderate MS, regular exercise can help improve your strength, muscle tone, balance and coordination. Swimming or other water exercises are good options if you have intolerance to heat. Other types of mild to moderate exercise recommended for people with MS include walking, stretching, low-impact aerobics, stationary bicycling, yoga and tai chi.

- Cool down. MS symptoms may worsen when the body temperature rises in some people with MS. Avoiding exposure to heat and using devices such as cooling scarves or vests can be helpful.

- Eat a balanced diet. Since there is little evidence to support a particular diet, experts recommend a generally healthy diet. Some research suggests that vitamin D may have potential benefit for people with MS.

- Relieve stress. Stress may trigger or worsen your signs and symptoms. Yoga, tai chi, massage, meditation or deep breathing may help.

More Information

Alternative medicine

Many people with MS use a variety of alternative or complementary treatments or both to help manage their symptoms, such as fatigue and muscle pain.

Activities such as exercise, meditation, yoga, massage, eating a healthier diet, acupuncture and relaxation techniques may help boost overall mental and physical well-being in patients with MS.

According to guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology, research strongly indicates that oral cannabis extract (OCE) may improve symptoms of muscle spasticity and pain. There is a lack of evidence that cannabis in any other form is effective in managing other MS symptoms.

Daily intake of vitamin D3 of 2,000 to 5,000 international units daily is recommended in those with MS. The connection between vitamin D and MS is supported by the association with exposure to sunlight and the risk of MS.

Coping and support

Living with any chronic illness can be difficult. To manage the stress of living with MS, consider these suggestions:

- Maintain normal daily activities as best you can.

- Stay connected to friends and family.

- Continue to pursue hobbies that you enjoy and are able to do.

- Contact a support group, for yourself or for family members.

- Discuss your feelings and concerns about living with MS with your doctor or a counselor.

Preparing for your appointment

You may be referred to a doctor who specializes in disorders of the brain and nervous system (neurologist).

What you can do

- Write down your symptoms, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason why you scheduled the appointment.

- Make a list of all your medications, vitamins and supplements.

- Bring any clinical notes, scans, laboratory test results or other information from your primary care provider to your neurologist.

- Write down your key medical information, including other conditions.

- Write down key personal information, including any recent changes or stressors in your life.

- Write down questions to ask your doctor.

- Ask a relative or friend to accompany you, to help you remember what the doctor says.

What to expect from your doctor

Your doctor is likely to ask you questions. Being ready to answer them may reserve time to go over points you want to spend more time on. You may be asked:

- When did you begin experiencing symptoms?

- Have your symptoms been continuous or occasional?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your symptoms?

- Does anyone in your family have multiple sclerosis?

Questions to ask your doctor

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- What kinds of tests do I need? Do they require any special preparation?

- Is my condition likely temporary or chronic?

- Will my condition progress?

- What treatments are available?

- I have these other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

In addition to the questions that you've prepared to ask your doctor, don't hesitate to ask other questions during your appointment.

Dec. 24, 2022