Overview

Head lice

Head lice

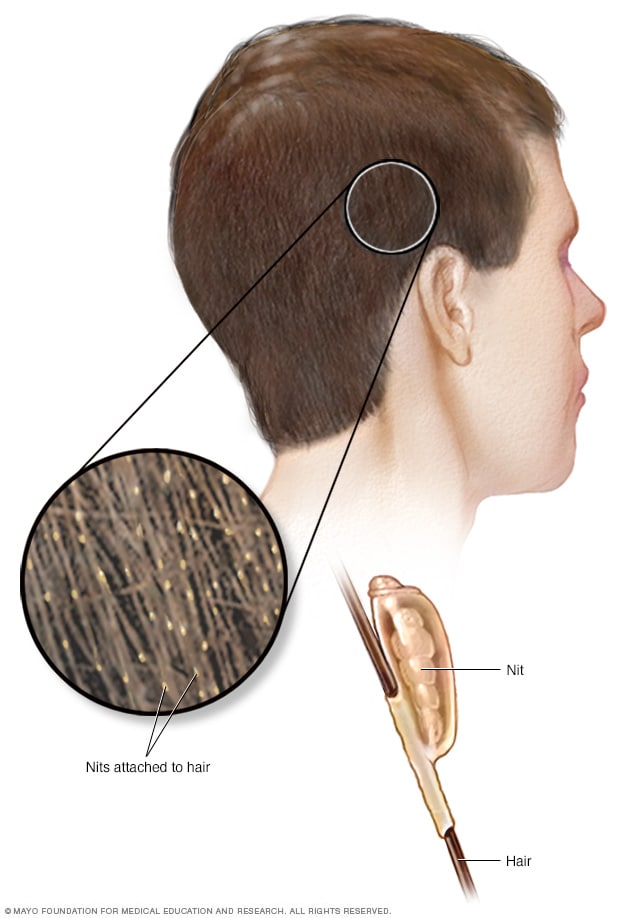

Head lice occur on the scalp and are easiest to see at the nape of the neck and over the ears. Small nits (eggs) resembling tiny pussy willow buds about the size of dandruff flakes are visible on hair shafts.

Lice are tiny, wingless insects that feed on human blood. Lice spread from person to person through close contact and by sharing belongings.

There are three types of lice:

- Head lice found on the scalp. They're easiest to see at the nape of the neck and over the ears.

- Body lice that live in clothing and bedding and move onto the skin to feed. Body lice most often affect people who aren't able to bathe or wash clothing often, such as homeless people.

- Pubic lice, also called crabs, that occur on the skin and hair of the pubic area. Less often, they may be found on coarse body hair, such as chest hair, eyebrows or eyelashes.

Unless treated properly, lice can become a recurring problem.

Symptoms

Head lice

Head lice

Head lice feed on blood from the scalp. The female louse lays eggs (nits) that stick to hair shafts.

Common signs and symptoms of lice include:

- Intense itching on the scalp, body or in the genital area.

- A tickling feeling from movement of hair.

- The presence of lice on your scalp, body, clothing, or pubic or other body hair. Adult lice may be about the size of a sesame seed or slightly larger.

- Lice eggs (nits) on hair shafts. Nits may be difficult to see because they're very tiny. They're easiest to spot around the ears and the nape of the neck. Nits can be mistaken for dandruff, but unlike dandruff, they can't be easily brushed out of hair.

- Sores on the scalp, neck and shoulders. Scratching can lead to small red bumps that can sometimes get infected with bacteria.

- Bite marks, especially around the waist, groin, upper thighs and pubic area.

When to see a doctor

See your health care provider if you suspect you or your child has lice. Things often mistaken for nits include:

- Dandruff

- Residue from hair products

- Bead of dead hair tissue on a hair shaft

- Scabs, dirt or other debris

- Other small bugs found in the hair

Causes

Lice feed on human blood and can be found on the human head, body and pubic area. The female louse produces a sticky substance that firmly attaches each egg to the base of a hair shaft. Eggs hatch in 6 to 9 days.

You can get lice by coming into contact with either lice or their eggs. Lice can't jump or fly. They spread through:

- Head-to-head or body-to-body contact. This may occur as children or family members play or interact closely.

- Closely stored belongings. Storing clothing that have lice close together in closets, lockers or on side-by-side hooks at school can spread lice. Lice also can spread when storing personal items such as pillows, blankets, combs and stuffed toys together.

- Items shared among friends or family members. These may include clothing, headphones, brushes, combs, hair accessories, towels, blankets, pillows and stuffed toys.

- Contact with furniture that has lice on it. Lying on a bed or sitting in overstuffed, cloth-covered furniture recently used by someone with lice can spread them. Lice can live for 1 to 2 days off the body.

- Sexual contact. Pubic lice usually spread through sexual contact. Pubic lice most commonly affect adults. Pubic lice found on children may be a sign of sexual exposure or abuse.

Prevention

It's difficult to prevent the spread of head lice among children in child care and school settings. There's so much close contact among children and their belongings that lice can spread easily. The presence of head lice isn't a reflection of hygiene habits. It's also not a failure on the parent if a child gets head lice.

Some nonprescription products claim to repel lice. But more research is needed to prove their safety and effectiveness.

Many small studies have shown that ingredients in some of these products — mostly plant oils such as coconut, olive, rosemary and tea tree — may work to repel lice. However, these products are classified as "natural," so they aren't regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Their safety and effectiveness haven't been tested to FDA standards.

Until more research proves the effectiveness of head lice prevention products, the best approach is simply to take thorough steps to get rid of lice and their eggs if you find them on your child. In the meantime, these steps can help prevent lice:

- Ask your child to avoid head-to-head contact with classmates during play and other activities.

- Teach your child not to share personal belongings such as hats, scarves, coats, combs, brushes, hair accessories and headphones.

- Tell your child to avoid shared spaces where hats and clothing from more than one student are hung on a common hook or kept in a locker.

However, it's not realistic to expect that you and your child can avoid all contact that may cause the spread of lice.

Your child may have nits in his or her hair but may not develop a case of head lice. Some nits are empty eggs. However, nits that are found within 1/4 inch (6 millimeters) of the scalp typically should be treated — even if you find only one — to prevent the possibility of hatching.