Overview

The genetic basis of Down syndrome

The genetic basis of Down syndrome

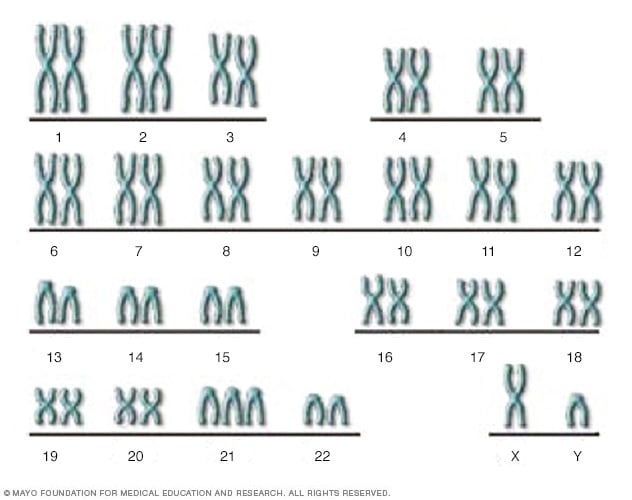

There are 23 pairs of chromosomes, for a total of 46. Half the chromosomes come from the egg and half come from the sperm. This XY chromosome pair includes the X chromosome from the egg and the Y chromosome from the sperm. In Down syndrome, there is an additional copy of chromosome 21, resulting in three copies instead of the usual two copies.

Down syndrome is a genetic condition caused when an unusual cell division results in an extra full or partial copy of chromosome 21. This extra genetic material causes the developmental changes and physical features of Down syndrome.

The term "syndrome" refers to a set of symptoms that tend to happen together. With a syndrome, there is a pattern of differences or problems. The condition is named after an English physician, John Langdon Down, who first described it.

Down syndrome varies in severity among individuals. The condition causes lifelong intellectual disability and developmental delays. It's the most common genetic chromosomal cause of intellectual disabilities in children. It also commonly causes other medical conditions, including heart and digestive system problems.

Better understanding of Down syndrome and early interventions can greatly improve the quality of life for children and adults with this condition and help them live fulfilling lives.

Products & Services

Symptoms

Each person with Down syndrome is an individual. Problems with intellect and development are usually mild to moderate. Some people are healthy while others have serious health issues such as heart problems that are present at birth.

Children and adults with Down syndrome have distinct face and body features. Though not all people with Down syndrome have the same features, some of the more common features include:

- Flattened face and small nose with a flat bridge.

- Small head.

- Short neck.

- Tongue that tends to stick out of the mouth.

- Upward slanting eyelids.

- Skin fold of the upper eyelid that covers the inner corner of the eye.

- Small, rounded ears.

- Wide, small hands with a single crease in the palm and short fingers.

- Small feet with a space between the first and second toes.

- Tiny white spots on the colored part of the eye called the iris. These white spots are called Brushfield's spots.

- Short height.

- Poor muscle tone in infancy.

- Joints that are loose and too flexible.

Infants with Down syndrome may be average size, but typically they grow slowly and remain shorter than other children the same age.

Developmental delays

Children with Down syndrome take longer to reach developmental milestones, such as sitting, talking and walking. Occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech and language therapy can help improve physical functioning and speech.

Intellectual disabilities

Most children with Down syndrome have mild to moderate cognitive impairment. This means that they have problems with memory, learning new things, focusing and thinking, or making decisions that affect their everyday life. Language and speech are delayed.

Early intervention and special education services can help children and teens with Down syndrome reach their full potential. Services for adults with Down syndrome can help support living a full life.

When to see a doctor

Down syndrome usually is diagnosed before or at birth. But if you have any questions regarding your pregnancy or your child's growth and development, talk with your doctor or other healthcare professional.

Causes

Human cells usually contain 23 pairs of chromosomes. One chromosome in each pair comes from the sperm, the other from the egg.

Down syndrome results from an unusual cell division involving chromosome 21. This unusual cell division results in an extra partial or full chromosome 21. This extra genetic material changes how the body and brain develop. It is responsible for the physical features and developmental problems of Down syndrome.

Any one of three genetic changes can cause Down syndrome:

- Trisomy 21. About 95% of the time, Down syndrome is caused by trisomy 21. This means the person has three copies of chromosome 21, instead of the usual two copies. The extra chromosome 21 is in all cells in the body. Trisomy 21 results from an unusual cell division during the development of the sperm cell or the egg cell.

- Mosaic Down syndrome. This is a rare form of Down syndrome. People with mosaic Down syndrome have only some cells with an extra copy of chromosome 21. This mosaic of typical and changed cells is caused by an unusual cell division after the egg has been fertilized by the sperm.

- Translocation Down syndrome. In a small number of people, Down syndrome can occur when a part of chromosome 21 becomes attached, also called translocated, onto another chromosome. This can happen before or at conception. The person has the usual two copies of chromosome 21, but also has extra genetic material from chromosome 21 attached to another chromosome.

Is it inherited?

Most of the time, Down syndrome is not passed down in families. The condition is caused by a random unusual cell division. This can happen during the development of the sperm cell or the egg cell or during early development of the baby in the womb.

Translocation Down syndrome can be passed from parent to child. But only a small number of children with Down syndrome have translocation and only some of them inherited it from one of their parents.

Either parent may have a balanced translocation. The parent has some rearranged genetic material from chromosome 21 on another chromosome, but no extra genetic material. This means the parent has no signs of Down syndrome, but can pass an unbalanced translocation on to children, causing Down syndrome in the children.

Risk factors

Some parents have a greater risk of having a baby with Down syndrome. Risk factors include:

- Older age. Chances of giving birth to a child with Down syndrome goes up with age because older eggs have a greater risk of unusual chromosome division. The risk of having a child with Down syndrome increases after a pregnant person is 35 years of age. But most children with Down syndrome are born to pregnant people under age 35 because they have far more babies.

- Being carriers of the genetic translocation for Down syndrome. Either parent can pass the genetic translocation for Down syndrome on to their children.

- Having had one child with Down syndrome. Both parents who have one child with Down syndrome and parents who have a translocation themselves are at higher risk of having another child with Down syndrome. A genetic counselor can help parents understand the risk of having a second child with Down syndrome.

Complications

Health concerns that result from having Down syndrome can be mild, moderate or severe. Some children with Down syndrome are healthy, while others may have serious health problems. Some health concerns may become more of a problem as the person gets older.

Health concerns can include:

- Heart problems. About half the children with Down syndrome are born with some type of heart condition that is present at birth. These heart problems can be life-threatening and may require surgery in early infancy.

- Problems with the digestive system and digesting food. Stomach and intestinal conditions occur in some children with Down syndrome. These may include changes in the structure of the stomach and intestines. There is a higher risk of developing digestive problems, such as intestinal blockage, heartburn called gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or celiac disease.

- Problems with the immune system. Because of differences in their immune systems, people with Down syndrome are at higher risk of developing autoimmune disorders, some forms of cancer and infectious diseases such as pneumonia.

- Sleep apnea. Soft tissue and spinal changes can lead to blockage of the airways. Children and adults with Down syndrome are at greater risk of obstructive sleep apnea.

- Being overweight. People with Down syndrome are more likely to be overweight or obese compared with the general population.

- Spinal problems. In some people with Down syndrome, the top two vertebrae in the neck may not line up as they should. This is called atlantoaxial instability. The condition puts people at risk of serious injury to the spinal cord from activities that bend the neck too far. Some examples of these activities include contact sports and horseback riding.

- Leukemia. Young children with Down syndrome have a higher risk of leukemia.

- Alzheimer's disease. Having Down syndrome greatly raises the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. Also, dementia often occurs at an earlier age than in the general population. Symptoms may begin around age 50.

- Other problems. Down syndrome also may also be linked with other health conditions, such as thyroid problems, dental problems, seizures, ear infections, and hearing and vision problems. Conditions such as depression, anxiety, autism and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) also may be more common.

Life expectancy

Over the years, there have been advances in healthcare for children and adults with Down syndrome. Because of these advances, children born today with Down syndrome are likely to live a longer life than in the past. People with Down syndrome can expect to live more than 60 years, depending on how severe their health problems are.

Prevention

There's no way to prevent Down syndrome. If you're at higher risk of having a child with Down syndrome or you already have one child with Down syndrome, you may want to talk with a genetic counselor before becoming pregnant.

A genetic counselor can help you understand your chances of having a child with Down syndrome. The counselor also can explain the prenatal tests that are available and help explain the pros and cons of testing.

Nov. 12, 2024